While we aim to discuss a wide breadth of films each year, few things give us more pleasure than the arrival of bold, new voices. It’s why we venture to festivals and pore over a variety of different features that might bring to light some emerging talent. This year was an especially notable time for new directors making their stamp, and we’re highlighting the handful of 2015 debuts that most impressed us.

This shouldn’t discount the breakthrough directors behind such films as Buzzard; Tangerine; It Follows; Heaven Knows What; Kumiko, The Treasure Hunter; Man From Reno; and Spring, to name some we liked, but considering that they all have at least two features under their belts, we’re strictly focusing on first-timers here. Below, one can check out a list spanning a variety of different genres and distributions, from those that barely received a theatrical release to wide bows. In years to come, take note as these helmers (hopefully) ascend.

‘71 (Yann Demange)

Perhaps the ideal way to kick off this list is Yann Demange‘s debut, which isn’t the best of its kind this year, but does announce a director with a great deal of promise. ’71 tracks the intense, fictional story of Gary Hook (Jack O’Connell), a British soldier sent to Belfast who gets separated from his regiment during a riot. Melding the feel of High Noon with an execution not unlike Die Hard — at least in the second half — Demange unfolds his story with immediacy at every turn, backed by another passionate performance from O’Connell. Despite succumbing to a few tired narrative pitfalls, the writer-director’s made us greatly anticipate what comes next. – Jordan R.

Bone Tomahawk (S. Craig Zahler)

Of all the cinematic genres, it is the western that has the most malleability and is somehow paradoxically seen as the most staid. When a person thinks of a western they think of men in hats riding horses in the sunlight and handling six-shooters, all things which seem, at their core, to make a story old-fashioned. But we’ve had period westerns, modern westerns, space westerns, and everything in-between, so it should be clear by now that the genre can be whatever you want it to be – even a horror film. Director S. Craig Zahler locates that truth and creates a stunning new experience with Bone Tomahawk. Perfectly paced, beautifully shot, and with an even tonal hand that gives dialogue and action scenes a sense of narrative consistency, Zahler explodes onto the scene with such assuredness that it is a surprise to find this is his first film. With so much certainty behind the camera on the first outing, where can the man go from here? Hopefully, wherever he wants. – Brian R.

Christmas, Again (Charles Poekel)

Christmas time is a lonely time for many; a “time of giving” that reminds more than a few of us what we’ve lost. This is the feeling Christmas, Again wades in, as produced, written and directed by Charles Poekel. We follow Noel (Kentucker Audley), who’s selling Christmas trees on a Manhattan curb for the fifth winter in a row. He’s getting over a recent break-up and working with the younger brother of the friend that used to be his partner. It’s a lonely state of affairs, Noel waking up for the night shift, taking medication, sweeping the pine needles off of the curb, etc. Audley is an extremely talented young actor whose been around for some time now, supporting in fellow Sundance movies like V/H/S and Ain’t Them Bodies Saints. Here, in the lead, he proves vulnerable and endearing, building an authentic character to care about and root for even during these smallest of trials and tribulations. In 80 minutes, you will learn more about the art of selling Christmas trees than you ever wanted to know. – Dan M.

The Diary of a Teenage Girl (Marielle Heller)

Marielle Heller‘s stunning debut, based on Phoebe Gloeckner‘s 2002 graphic novel of the same name, is an outstanding coming-of-age story. Set in San Francisco during the 1970s, it follows Minnie Goetze (Bel Powley), a young teenage girl experimenting with her sexuality, drugs, and more. In the opening scene, which features Dwight Twilley’s “Looking for the Magic,” Minnie is walking on a high: she’s just had sex for the first time. The problem is, she had sex with her mother’s (Kristen Wiig) boyfriend, Monroe (Alexander Skarsgård). To see the world through Minnie’s eyes will hold one’s attention from beginning to end, but once one exits the theater, it’s impossible not to reflect on the decisions we’ve all made as a teenager — namely the mistakes. – Jack G.

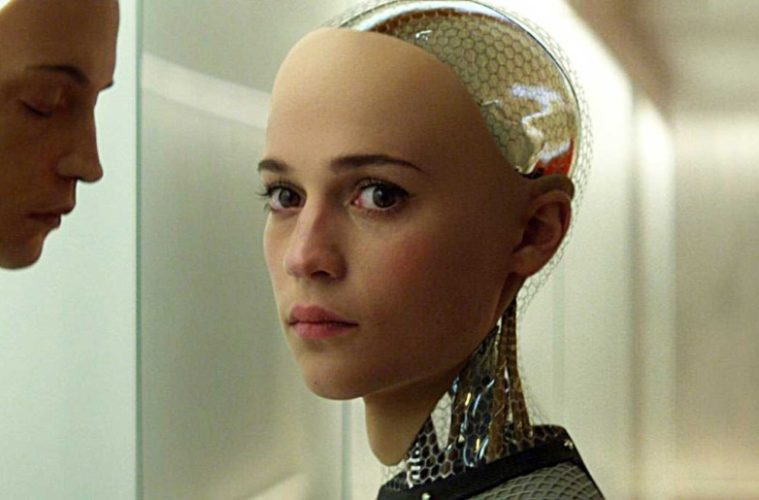

Ex Machina (Alex Garland)

Modern science fiction often leans towards fantasy with science elements, which is to say that a spaceship or a laser gun might be involved. Ex Machina attempts the difficult feat of grounding a science fiction story in what is, conservatively, the future of a few hours from now. That it succeeds as a thought experiment with a narrative frame is wonderful, but that it further succeeds as a thriller is downright impressive. Alex Garland — who is directing for the first time after writing some of the most interesting movies of the last few years — uses cleanly modernist interiors and crackling dialogue to tell this story, and his command of tone in the face of so much thought and speech is laudable. Rather than get bogged down in morose speechifying, he plays off of the expressive faces of his leads and the way in which their environment pens in or opens up conversations. It is a wickedly thoughtful chamber piece. – Brian R.

Faults (Riley Stearns)

The best film for a debut feature is often very dialogue-heavy. The lack of major set pieces or crazy stunts means that costs and risks are low, and bare-knuckle filmmaking can shine through – just as long as the story and the filmmaking remain interesting enough to sustain the cerebral conversations. Riley Stearns sidesteps the pitfall of the “dull, talkative indie debut” by crafting a truly compelling story and shooting it with a paranoid eye that keeps the energy high and the intrigue at a fever pitch. Making the most of its nearly single-location story, Stearns keeps us on our toes with ingenious plotting, nightmare editing, and firm point-of-view storytelling. Rather than let himself rest on the powers of his actors, he uses the camera to put us in their headspace, and the resulting investment pays off in many of this film’s clever twists and turns. – Brian R.

The Gift (Joel Edgerton)

In his thoroughly strategized directorial debut The Gift, actor-writer Joel Edgerton recognizes curiosity as a seed. He plants one hardly five minutes in, based on the relatable subject of weird people you knew in high school, and the self-amusement in seeing how they’ve turned out years later. In its more sophisticated aspects, The Gift is the triumph of an acting-writing-directing triple-threat who knows what an audience wants and also just what they need. Edgerton is able to orchestrate tension without solely relying on it, and through the common ground of awkward human interaction creates a horror villain far more traumatizing than the boogeymen found in other Blumhouse projects. His picture only gets stronger when it evolves to drama, its tale of born-winners and -losers providing the deepest cut. – Nick A.

Güeros (Alonso Ruizpalacios)

What’s on the screen is often (to use a phrase that everyone understands and no one entirely agrees upon) over-directed, but Güeros’ visual eccentricities — a camera spin here, an extended dolly shot there, a handheld run through the streets in-between them — are tampered by Alonso Ruizpalacios’ understanding of what’s on the page: a road-trip movie with more than a few digressions and little sense of the final destination’s importance. While sometimes reminiscent of Y Tu Mamá También – a comparison perhaps boosted by Gael García Bernal’s producing credit — this is its own beast, often shot and edited with a far more rigid sense for space and movement. If Ruizpalacios can continue to hone his sensibilities and pen effectively structured tales (co-writer Gibrán Portela obviously deserves some credit here), this could eventually be seen as the start of something special. I’d really be pleased if Güeros isn’t a one-time deal. – Nick N.

James White (Josh Mond)

In the five months found within James White, our title character is at the most difficult chapter of his life thus far. He’s grieving the loss of his father and attempting to assist his ailing mother, and the drama authentically depicts the brutality of that process. After producing the gripping Sundance dramas Martha Marcy May Marlene and Simon Killer, Josh Mond diverts in some ways with his directorial debut. While providing yet another intimate character study of a fractured individual, James White also has a perhaps unexpected, enveloping warmth.While lesser, perhaps more commercial films might shy away from the actual process of decay and loss, Mond displays no fear in vividly walking us through the bleak events in James White’s journey. – Jordan R.

The Mend (John Magary)

With its iris-in opening, quick succession of establishing scenarios, and punk-rock opening credits, The Mend initially strikes like a lightning bolt, only to settle into a burned-out, melancholy groove so thorough — so specific in atmosphere, tempo, cinematographic sense, and the certain musicality of its editing, while also terribly relatable in its anger and sadness — that one is prompted to ask: where did this even come from? Given a summary of writer-director John Magary’s feature debut — in which two distant brothers reconnect in a New York apartment as both struggle with romantic relationships — it sounds, well, familiar. The devil is in the details: a tight-as-a-drum-snare script, filled with lines that bounce around the mind for weeks (or months) after; the balance of Josh Lucas, Stephen Plunkett, and Lucy Owen’s performances (vicious bitterness, subdued bitterness, and a frayed sense of adulthood, respectively); numerous passages syncing sound, image, and headspace; or the shocking behavior of primary and tertiary characters, which lends it an anything-can-happen feeling. (Or something like that. Maybe you should just see the movie to figure it out for yourself.) Magary’s follow-up, whatever it may be and whenever it may come, is greatly anticipated. – Nick N.

Mustang (Deniz Gamze Ergüven)

Every so often a film comes across as so authentic, intimate, and accomplished, that one imagine sits director has spent decades building their artistic voice. Consider the surprise when they learn that Mustang is Deniz Gamze Ergüven‘s feature debut. France’s Oscar entry — which, to some controversy, they picked over the Palme d’Or-winning Dheepan — tells the story of a group of sisters in Turkey who battle societal and familial pressures to conform to a structured life of arranged matrimony. Brimming with humanity, it’s a joyous, heartbreaking, and deeply affecting celebration of independence and sisterhood. – Jordan R.

Partisan (Ariel Kleiman)

Whether it’s Martha Marcy May Marlene or Sound of My Voice or this year’s The Wolfpack, we’ve seen a number of Sundance films that deal with communes and closed communities, but few bring the level of danger found in Partisan. The directorial debut of Ariel Kleiman is a patiently unfolding drama that displays the lengths one will go to provide shelter and community — and what happens if you step out of bounds. Vincent Cassel provides a chilling, commanding performance as the commune’s leader, complete with both the compulsory patriarch traits and the lingering sadness of what he’s doing. – Jordan R.

Son of Saul (László Nemes)

László Nemes‘ debut is dominated by traveling long takes, rushing along with our as he attends to his horrifying tasks in frenzied succession, all the while struggling through an incessant barrage of screaming, shoving and beating. Saul is thus established as a mere cog in a gigantic and unfaltering industrial machine. The technical prowess involved is immense, all the more so for having used an unwieldy 35mm camera: in their movements, pace, proximity and duration, the shots are exceptionally complex, yet they are executed with the utmost precision and always kept in perfect focus. The result is claustrophobic and overwhelmingly intense and the film barely slows down for a single one of its 107 minutes. As a viewing experience, it is relentlessly harrowing, bordering on the traumatizing. Yet while Son of Saul dares to delve even further into the horror than the majority of Holocaust films, never once does it so much as threaten to slip into exploitative territory. – Giovanni M.C.

Slow West (John Maclean)

I previously made a point that a western could be anything that its creator wanted it to be, and, to add further fuel to my rhetorical fire, I offer Slow West. Director John Maclean brings a strange, whimsical touch to this story of wandering on the open range and mountainous frontier, and the movie sings for it. Whereas Bone Tomahawk builds tension and character through stillness and patience, Slow West creates a bizarre dreamscape through intimacy and lightness. Episodic in the best of ways, this film gives equal time to major action and lyrical interludes, and allows for humor both in character and incident, with Maclean taking the time to focus on pieces of the story and tiny ironies that other directors wouldn’t bother with. It’s the wryly grinning flipside to Bone Tomahawk’s blood-drenched sneer. – Brian R.

Uncle John (Steven Piet)

Sleepy thriller. Indie rom-com. Dark comedy. The debut feature from writer-director Steven Piet — who co-scripted the work with fellow first-timer Erik Crary — is all of those things and so much more. Besides balancing multiple genres with ease, this double-pronged story of a retired farmer, a big-city office worker, and a murder cover-up stands apart with dynamic parallel editing, charming characters, and a knack for capturing the simple beauty of modern-day rural America. Complete with a real nail-biter of a climax, Piet has managed to deliver one of the year’s most pleasant and masterful surprises. – Amanda W.

What’s your favorite directorial debut of the year?