Ahead of the Academy Awards, we’ve reviewed every short film in each category: Animation, Documentary, and Live Action. Here are the Best Live Action Short nominees:

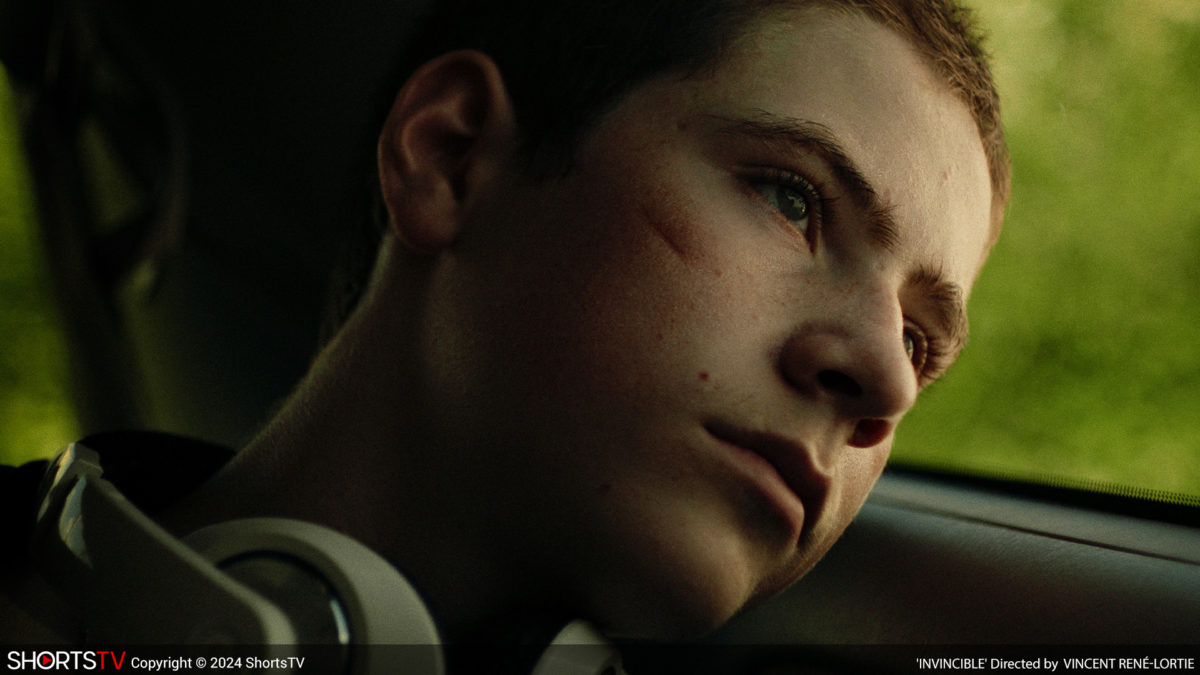

Invincible | Canada | 30 minutes

The line “I’ll never be in your position” hits hard about halfway through Vincent René-Lortie’s Invincible. We’ve already seen it come true because of where Marc (Léokim Beaumier-Lépine) ends up––courtesy the prologue-set future that unfolds before the short film rewinds backwards in time––but those words are less premonition than tragic reality. He speaks them in response to his juvenile-detention-center case worker (Ralph Prosper’s Luc) asking what he should do about the boy’s latest transgression. Despite good grades and an empathetic heart, Marc finds himself on a path that does not lead towards authoritative roles. His past deeds have marked him. His present resentments have destroyed hope.

Based on true events, Marc’s dual nature pushes and pulls him off the line that separates the artistic soul within from the troublemaking grin on the surface. Will he listen to Luc’s words and realize he can still earn his ticket out? Or will he let impatience and fear drive him to escape and discover running isn’t freedom? We want to believe it will be the former. Maybe he’ll even point out the latest security flaw to Luc to prove he can be trusted after all. Even knowing what we know, we can’t yet relinquish our own hope for him. Because believing that kids like Marc are inherently beyond help is akin to giving up on humanity itself.

René-Lortie does a phenomenal job distilling this story to its barest bones so emotion can carry the narrative rather than plot. He neither wastes time telling us what Marc did wrong nor leave us hanging with cliffhangers diluting the potency of where this tale must go to deliver the message at its center. And Beaumier-Lépine supplies the role an unparalleled authenticity from the opening’s tearful silence to the final cut to black. The complexity and contradictions of this teenager resonate to ensure he remains three-dimensional despite a trajectory that could easily fall into cliché. Because Marc isn’t a bad kid. He’s merely a desperate one who can no longer see the promise of tomorrow.

B+

Knight of Fortune | Denmark | 25 minutes

Karl (Leif Andrée) isn’t ready to lose Karen. Knowing that opening her coffin makes it real, he does everything possible to avoid the act. Attempting to fix a faulty fluorescent light in the chapel. Hiding in a bathroom stall. Joining another grieving widower in need of a friend. We want to believe that helping the latter (Jens Jørn Spottag’s Torben) push through his anxieties might help Karl, too, but the situation gets complicated when another family suddenly joins in. Heartbreak moves towards embarrassment as the heavy drama is hit with a healthy dose of humor. Yet Karl still must eventually say goodbye.

Lasse Lyskjær Noer’s Knight of Fortune possesses the best type of unpredictability––the kind that surprises in its absurdity without losing the authenticity that prevents it from becoming absurd. Yes, certain revelations will make you laugh despite the somber environment, but none feel false. Death just tends to make people do crazy things. To ask others to join an objectively inappropriate (albeit superficially harmless) act and / or force yourself to lie so you can save face and, perhaps, the day too.

The script itself is a huge part of its success, both via the main thrust of Karl finding the strength to be vulnerable and the surrounding bits of deadpan comedy––e.g. extremely thankful mourners and an undertaker (Jesper Lohmann) turning the air even more uncomfortable by needing to corral his intern. For my money, though, it’s Andrée and Spottag who shine brightest by delivering touching portraits of sorrow interrupted by second-hand embarrassment and a mortifying fear of being somewhere they shouldn’t. Them breaking into laughter two-thirds of the way through is such a salve for the soul and exactly the levity needed to finally get things back on track.

Because Karl can’t be allowed to run away and ultimately regret never seeing his love one last time. The journey there isn’t routine, but the chaos provides the perfect avenue towards accomplishing what he must by simultaneously lessening the burden on his heart and ensuring he recognizes how that burden isn’t uniquely his. Anyone who has ever dealt with loss knows it. And anyone who has ever said their goodbyes knows that type of closure can sometimes prove their only relief. Torben’s presence thus exposes that truth for Karl while Karl’s courage to say the words presents Torben with that which he tragically cannot experience himself.

A-

Red, White and Blue | USA | 23 minutes

It’s a modern-day Call Jane of sorts. We meet Rachel (Brittany Snow) as she stares down at a pregnancy test, unsure what to do. Already barely scraping by as a single mother of two young children, abortion is the only option that ensures they won’t all starve to death. Unfortunately, the procedure is no longer available in every state. And being that Rachel lives in Arkansas, she must cross more than one such anti-abortion border to find a clinic willing to treat her. What should cost a couple hundred dollars a short drive away suddenly balloons to over a thousand on a two-day trip.

That’s the reality of living as a woman in the good ol’ Red, White and Blue. And since it’s one that has been intentionally created to force women into reaching full-term no matter their circumstances or age, writer/director Nazrin Choudhury uses her short to highlight the anonymous sisterhood willing to risk their own freedom to make certain those like Rachel aren’t stripped of theirs. Maybe it’s a bystander who can read between the lines and offer financial assistance. Maybe it’s a nurse who acknowledges the desperation on a patient’s face before moving her up the queue.

The first two-thirds of the run-time proves a solid narrative doing its best not to preach as much as reveal the unavoidable truths of our post-Roe v. Wade world. The camera does well to show us that Maddy (Juliet Donenfeld) and Jake (Redding Munsell) are too important to Rachel to even consider the alternative. Some moments are overt for easy contrast—a misogynistic customer smacking her butt while her boss shrugs his shoulders—but stereotypes are concise. So too are nightmarish reveals at the eleventh hour. You can’t say that where Choudhury takes this story isn’t manipulative, but you also can’t say isn’t powerful.

It’s only when the obvious Call Jane concept is spoken aloud via a clunky end-scene monologue that you pause to wonder if you’ve been giving the whole a benefit of the doubt it doesn’t quite earn. I personally believe it still does since imperfect execution shouldn’t fully negate an effective and important message told in an impactful way, but I wouldn’t begrudge audiences for disagreeing. The unfortunate truth, however, is that the audiences who need that message will use this manipulation as an excuse to dismiss it as “liberal propaganda.” Not that they wouldn’t have done so anyway, the twist simply ensures it.

B-

The After | UK | 18 minutes

Sometimes the constraints of a short film’s length can augment the emotional potency of its subject matter; sometimes it ensures the drama will never transcend its artificial approximation of the truth. Misan Harriman’s The After (written by John Julius Schwabach from a story originated by the director) sadly falls into the latter category. It wants us to feel for Dayo (David Oyelowo) as he grieves, but it’s too interested in the idea of catharsis to allow the act the necessary room to unfold as more than the result of an actor following script directions.

Oyelowo is good, though. He does everything he’s asked. Pushing him through the stages his character must travel as if it’s a clinical process rather than an organic one sadly does him no favors. The script is too rigid, the trajectory to obvious to foster any spontaneity. When Dayo finally chooses family above work, he’s punished for it. Then, in a bid to wall himself off from the world, this businessman inexplicably pivots to rideshare driving (!) wherein he’s forced to endure constant triggers that remind him of what he has lost? By the time release finally arrives, we don’t know its point. Is he unceremoniously healed? Merely relieved to finally cry?

I also can’t shake the idea that this detachment between us and the character might be intentional. Harriman is a photographer making his directorial debut, and many moments feel meticulously designed towards aesthetic purity at the price of authenticity. The scene where he’s lying on top of an assailant with two other Samaritans only to have them drag the criminal away so the camera can capture the Oscar-bait shot of Oyelowo’s shock epitomizes this, the act so theatrically pre-planned. They might as well have let them get up and walk away, breaking the fourth to not pretend that the purpose is having the protagonist emote without competition.

And I don’t even know what to think about the ending. If having Dayo drive a family that reminds him of his own to conjure a response isn’t manipulative enough to ruin the moment’s potential gravitas, subverting his climactic melodramatic moment by having that family completely ignore his pain so they can leave the frame as quickly as those Samaritans lends an unintentional humor to the whole that fully undercuts Oyelowo’s performance. The film is toeing this line between realism and artifice in a way that makes it seem unfinished. I kept waiting for Harriman to yell cut and have the camera zoom out to show the set and crew, officially giving life to its big-time “rehearsal exercise” energy.

C-

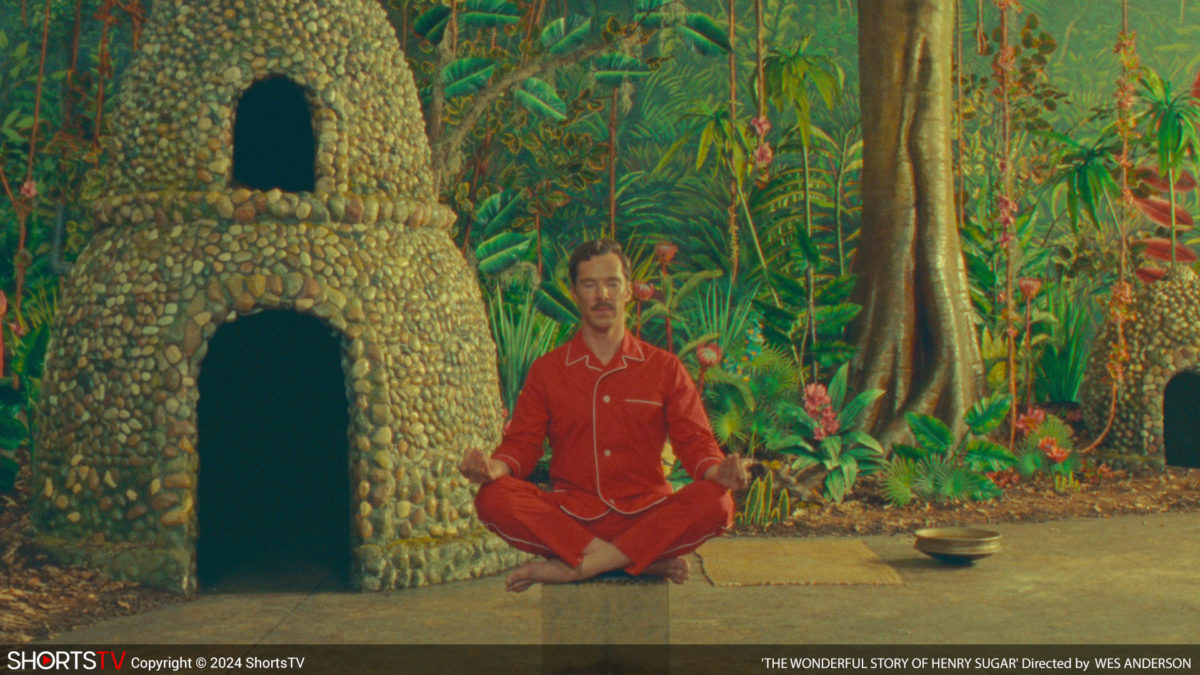

The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar | UK/USA | 37 minutes

What an inspired choice to not only have his actors read their own narration––often speaking to another character before turning to the camera to breathlessly continue the exposition to us––but also have them speak it at lightning speed to ensure Roald Dahl’s The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar clocks in at just under 40 minutes. Wes Anderson could have easily expanded it out to feature length by slowing down and adding back the passages he cut and / or truncated visually with aplomb, but he sought to make a collection of short films out of the famed author’s short stories instead. It’s a purposeful, fanciful, entertaining aesthetic.

So too is the production design. Shot in full frame (even shifting the camera in some moments to turn the square composition into a vertical) with fun, layered sets resembling those we used to make for school plays, the whole progresses more like a theater show than a film, with its fourth-wall-breaking performances and visible stagehands keeping everything in rhythm. Props are handed to actors and given back. Actors perform multiple roles to keep the main troupe as small as possible (five leads and a bunch of extras) and the costuming and make-up even become diegetic gags to fuel the artificial nature of the whole feeling like a puppet show of real people stiffly pulling their own strings.

Benedict Cumberbatch delivers a great deadpan Sugar––necessary, considering how effortlessly clinical the character moves from being an uncaring man of unearned wealth to a methodical Robin Hood (albeit selfishly so). Ralph Fiennes plays Dahl himself (a self-insert crucial to the story’s eccentric “true life” nature) while Ben Kingsley lets Anderson poke fun at his age by constantly making his character “younger” before then having him play an even “younger” second role that he could have written older without the added charm of the juxtaposition. For my money, though, it’s Dev Patel and Richard Ayoade who really embrace the exercise and tone. All five are Brits and experts in dry humor, but those latter two are bringing next level genius.

Like the visual aesthetic, this tone is also a very conscious creative choice on Anderson’s part to inject some life into a rather straightforward, droll telling of an off-kilter tale. When reading the short story before pressing play, I also found myself rushing through it with a similar staccato beat, each line brief and to the point to tell us everything we need to know without wasting time with superfluous detail. It’s thus perfectly suited for the decision to let performance fill in the gaps. To let the actors channel our perspective as viewers right alongside their perspective as the characters they play, reacting to the job as well as the material. It’s a delightful romp that leans into Anderson’s own style while retaining the joy and humor of Dahl’s prose. They truly are a match made in creative heaven.

B+

Starting February 16, the 19th annual Oscar® Nominated Short Films releases, presented by ShortsTV, will debut in theaters only. To learn more about the participating theaters and how to purchase tickets, please visit www.shorts.tv/theoscarshorts.