Legendary documentary filmmaker Steve James has a gift for effortless empathy. His films have a pre-natural ease with their subjects, chronicling the ordinary and extraordinary with equal levels of awe, and regularly showcasing an ability to enter his subjects’ inner most sanctums without feeling intrusive. James’ films are primarily observational with a few exceptions, but there’s never a sense that James’ camera is anything less than an old friend.

His latest film, Abacus: Small Enough To Jail, is a formal and tonal departure, but also a reiteration of some of James’ most prevailing thematic interests – namely underexposed communities and their mistreatment. A procedural probing into the stranger than fiction court saga of Abacus, a Chinatown bank plagued with wide-scale fraud, it’s anything but a pedestrian court film.

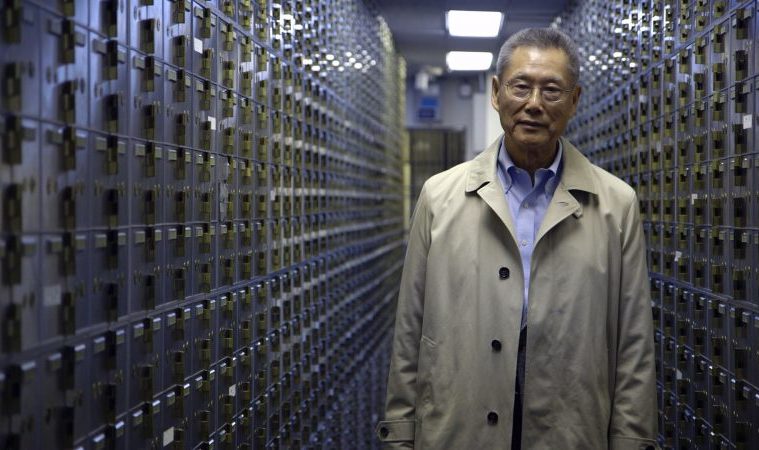

Embracing the disadvantages of recounting an ongoing court case — James and his crew were barred from filming the trial, and were unsure if they would have access to either the prosecution or defense team — Abacus instead leans into the outsized personalities of the Sung family. Patriarch Thomas Sung is a classic figure of martyrdom while his daughters epitomize the double edged sword of being deeply involved in both an immigrant community and a family business.

With the film now in theaters, I talked with James about making Abacus and his career as a whole. In a sprawling conversation, we talked about the process of making his first procedural without all the pieces, the benefits to filming in your hometown, and even broadly about the state of modern documentary film ethics.

The Film Stage: I know that your long time producer, Mark Mitten, was personally familiar with one of the main subjects of Abacus, Vera Sung, and came to you with their story while you were making Life Itself, but what was the genesis of this film?

Steve James: Well, that’s partially correct. It wasn’t while we were doing Life Itself that I found out about it. That film was done, but Mark Mitten was an executive producer on Life Itself, and someone that I’ve known for about ten years. And so it was him that brought it to my attention literally back in 2015 right around the beginning of the trial. That’s when he talked to me about it, and he said, “There’s this crazy trial about to kick off, and I know this family. I’ve known them for a long time. It seems like an important story.”

So you became involved literally right as the trial was beginning then?

Yes, yes, because we didn’t start filming until then, and I didn’t know about the story until then. The spine of the film really is the beginning of the trial through the end, and the decision. But you know, there are other things that we got — New York District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr.’s press conference back in 2012, for instance. We were able to get archival material that takes you back to that time, but our filming covered the trial basically. It was a five-month trial, and then we filmed afterwards. And you know we did interviews and stuff after the conclusion of the trial.

I know it’s probably instinct or an intangible quality, but what was it initially about meeting the Sung family that made you think you wanted to pursue a film or larger project? Was there something specific, or was it just the process of spending time with the family?

It was a combination of learning more about the situation of the trial, what was going on, what they were up against, and just further understanding that. Here’s this bank going through this, and no one seems to be paying any attention to it from a media standpoint, which when you’re a documentary filmmaker is not a bad thing. [Laughs] You feel like you’re telling a story that other people are not telling. And frankly, I was surprised that no one was really following it. The New Yorker eventually did a piece, and that reporter [Jiangyan Fan] was in the court regularly, and she became a great interview for us as a result of that. So it was a combination of that, and learning more about the particulars of what they were up against, and why they were brought to trial. But then a very big part of it was just meeting Mr. Sung and the sisters. I didn’t meet Mrs. Sung until later. I didn’t meet her on the first trip, but she was a gift from the documentary gods [laughs] yet to come. But just meeting the family, and finding them engaging, strong-willed, funny. Everything about them, I would have had to be an idiot to not grasp how interesting they were as subjects. But there was a point in that filming – and I made the decision very quickly – but it became clear that we weren’t going to be able to get in the courtroom. The DA’s office was not going to cooperate in any way during the trial. And there was a real question — although it was resolved in the first shoot — as to whether the Sungs’ lawyers would really cooperate much until the trial was over. And so, I had to make a decision based on, well, we would literally just be following the story with the Sung’s family outside the courtroom, but I decided that alone was worth it because of them and the story.

That was a gamble, but I think it works here. There’s documentaries where you notice when a filmmaker doesn’t have the coverage, but even though you’re only able to have small touches like the door closing to the jury room, or the illustrations of a court artist, all of those elements work to the film’s benefit as it adds a layer of suspense, but also a grim inevitability as to where this story could go.

Yeah, that’s nice to hear. I think we had to decide in terms of the actual unfolding trial that given that we weren’t able to be in the courtroom — how were we going to tell that story. I knew that since we were going to be following the family in real time; like how would we when we got to putting this all together, how would we find a way to have the trial unfold in a way that was satisfying. So I knew that we would film the empty courtroom, and do those kinds of shots, which are pretty standard when you get into a courtroom for a trial, but I knew I wanted to do something more. That’s how we landed on the idea of using this phenomenal court illustrator to go and spend several days at trial, and do a bunch of illustrations that then became the foundation for visualizing the trial once we got to editing and decided which parts of the trial we were going to feature.

From my experience with your work, this seems to have the most procedural bent.

Yeah. [Laughs]

Had you ever had to specifically think about this much with a court room?

Well, no. This was a different kind of film for me. But if you look at my body of work, I do different things from time to time. My better-known work tends to be in the more observational mode of Hoop Dreams, The Interrupters, or even a film like Stevie, although Stevie was very different. It had a very personal aspect to it. So this was different, but so was Life Itself. I mean, Life Itself, was a biography on one level, and on a very big level, it was a biography of a famous person, which I hadn’t done before. And then this is a procedural. I hadn’t been going around being like, I’m really looking for a good courtroom film. You know, it just presented itself, and then I asked, what do I think the best way to try to tell this story is. Had we gotten the kind of access that I would have loved to have had — to the case, to the courtroom — It would have been a very different film than the one you saw. But I feel like filmmaking, as I go along in my career, that increasingly, what filmmaking is really about is dealing with what you don’t have, not just with what you’re fortunate to have, and still trying to find ways to tell a good story. And so this presented real challenges to the kinds of films I’ve done in the past. But I also welcomed that challenge. I welcomed the opportunity to try and tell a courtroom story, and one in which it’s not like sexy murder. It’s not sexy material, if you will. [Laughs] Part of the virtue of this for me was that all of this stuff was so freaking petty. And yet, they were putting this family through this for all these kinds of petty fraud that the family had even admitted that they had discovered and tried to deal with. I mean, I’m rambling, but I love trying to stretch myself as a filmmaker, and not just do the thing that I do a lot of that I enjoy doing greatly, which is to follow people around for a year or longer, and create a more vérité-related film.

You had pretty extensive access to a usually closed community with Chinatown, a place that is generally portrayed in cinema with a mystique and exoticism that’s rarely ever removed. What were your impressions of Chinatown, especially as an outsider?

Yeah, I think you’re right. It’s sort of like, part of the attraction to telling the story as we went along was to get this access to a community that is not easily accessible. I’ve been to Chinatown once or twice in my visits to New York over the years, but I wasn’t aware of how closed the community was when we started to film. But I found out pretty quickly that it was, and you know, Mr. Sung was really our passport into that community. Because of his stature in that community and all that he’s done in that community. And so it really was through him that we were able to be there in a way that went beyond just rolling up and shooting postcard shots of Chinatown. I loved that. That’s always true with every film that I’ve done. It’s sort of like the way into any community that’s not your community, and most every film I’ve done, if not every film I’ve done, is then about communities that aren’t mine. The key is always your subjects, and them bringing you into that community in a way that you would not otherwise have access. That was true with Mr. Sung, and that was exciting, and it was also confirming of his significance. It’s one thing to hear people say he’s a pillar in the community, it’s another thing to walk around with him and really see it.

Related to that, you spend some time with an activist, Don Lee, who has a couple of choice quotes, and advocates for the Sung family. Was there a large group who was defending the Sung family in the community, and could Lee have been a bigger part of the film?

He could have. He was a friend of the family, and he was one of those people that also helped with our access. He embraced the fact that we were making this film. He was hugely supportive of them. So even being with Don Lee in the streets of Chinatown was wonderful because if Mr. Sung was the mayor of Chinatown, then he was his right hand man. He was really an extremely well-known and well-liked and well-respected presence in that community, so we did spend time with him and he was one of these very outspoken people in the community about the family and their innocence. And so we didn’t follow him as such, except to the degree that you see in the film – but he was someone that very important to them for sure. And he’s there. We don’t lower-third him, but he was there that day we were waiting for the verdict. He was there in support of them, and hanging out with them.

I wanted to ask you a little about your remarks at the Cinema Eye Honors earlier this year.

You mean my jokes. [Laughs]

You definitely had jokes [laughs], but you spoke specifically about Weiner and ethics, and your quotes made me curious about your own views. I don’t have the whole context of the conversation, but you said, “Who among us wouldn’t have killed for access to this story. It makes me wonder what compromising photo Kriegman and Steinberg had of Anthony Weiner to be able to blackmail him.”

That was a joke though. I was attempting to be funny because then I said, no, I don’t want to see that photo actually. [Laughs]

I know [laughs], but I am still curious about your views about recent shifting approaches in documentary filmmaking. You’ve been a non-fiction filmmaker for going on thirty years, has your view toward documentary ethics changed or expanded? I’m speaking specifically of films like Weiner, or even something like Matthew Heinemann’s Cartel Land, films with an incredible level of access, but arguably muddy presentation of their respective conflicts.

I think the whole question of ethics in documentary is something that I think has always been there, but is increasingly one that deserves more discussion and debate among people who care about documentaries. I think that’s because the genre – we used to kind of think of documentary as genre, but that’s a wholly inadequate way to categorize a form of filmmaking that really traverses every kind of genre imaginable. There are comedy documentaries, there are horror films. What is The Act of Killing, if not a horror film? There are thrillers and caper films. That film about the dolphin slaughter, The Cove, was like the documentary version of Oceans 11. The medium is expanding in so many ways, including pushing the boundaries of what we define as non-fiction with re-enactments, animation, all manner of manufactured realities that then become documentaries. I think these questions of ethics are more with us now and more urgent than ever. I’m not one of those people that feels one should not manipulate, or one should not use fictional material — that that’s forbidden. I’m not one of those people at all, but as a rule, I think we need to maybe do better about being candid about what the lines are within the work itself, so that the audience is very much aware of what they’re watching. I think the self-reflexive aspect of examining one’s work within the work is something I think there could be more of. And sometimes whenever I find a film problematic from an ethical standpoint, it’s frequently because I feel like the film is attempting to present itself as a kind of truth without that reflexivity, or is questionable, and the film is not acknowledging its questionability.

One of the projects you’re currently working on is America To Me, a miniseries that follows high school students over the course of a year. You’ve chronicled high schoolers a bit in Head Games and then The Interrupters before that if I remember correctly, but what was it like returning to high schoolers?

Yeah, and even in that film, the focus really isn’t on high school students. There’s some families that have high school students who are at risk of head injury in the sports they’re playing. But I think in many ways, this is the first time i’ve really returned to kids like that since Hoop Dreams. In Hoop Dreams, a big part of that story that people may not remember when they remember the film takes place in schools and classrooms, and is focused around the academics of Arthur [Agee] and William [Gates] and where they’re succeeding and failing. That is a big part of that film that’s probably forgotten because the basketball and the family life is what you remember, but so yeah, it’s not been since then. I think one of the things that’s been exciting to me about this project, America To Me for me as a filmmaker is that i’m telling stories about kids and families who I have not profiled in the past. They’re not living on the West side of Chicago or Cabrini Green. These are stories of kids who are a different part of black and biracial America, kids who are in well-funded schools in Oak Park, who live in a very liberal community. It’s not like there’s not economic need at work in some of our stories. There is, but none of these kids are in danger of being murdered on the corner or falling prey to gangs. And so these are some stories that fascinate me that I want to tell that don’t conform to a lot of what not just the stories that i’ve told, but many filmmakers have told when they try to tell the stories of young black people.

I know you live in Oak Park, did it feel significantly different to be filming in your own community?

That’s a good question. First of all, because it’s a miniseries, I recruited some really talented collaborators who followed stories of kids. There were three other filmmakers involved, and they were each filming and following stories, as was I. So this is a very collaborative work. They didn’t live in Oak Park, even though i’m the one that lives there. It’s different because I have a history in the community, and I think the only reason this film even happened was because of that. It wasn’t because of my track record as a filmmaker, but because I lived there — for the community, for the school board, to vote to allow me in for the year and give access at a school that is struggling with these issues of achievement. That was a brave thing for the community to say yes to. It would have been a lot easier to say, No thanks. We’ll just struggle with it, but we don’t want a film made about it or a miniseries about it. I think all of those things only happened because I lived there. My kids went to that high school and the grade schools too, and so they were willing to take a risk with me to allow me and my team in.

Abacus: Small Enough to Jail is now in theaters.