At a time when freedom of expression titters on the brink in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, there’s something thrillingly contemporary about Kirill Serebrennikov’s Soviet-set musical drama. Early 1980s St. Petersburg proves a breeding ground of underground music as rebellion, however tacit, emerges in home-grown rock and punk. Leto’s melancholic ode to rough-and-ready counterculture proves ever more relevant as Serebrennikov, himself an avant-garde theater director, remains under house arrest in Moscow.

Serebrennikov gives us a fictionalized version of his youth in urban Leningrad–as it was then known–shot in cool monochrome amid dimly lit apartments and the grotty confines of a bohemian side on the Soviet margins. In a blistering opening sequence, we see that in a microcosm: a handheld camera follows a posse of girls as they climb through a toilet window to the back of Soviet rock concert. Inside the crowd can only sit and quietly nod their head–anything as vulgar as dancing or waving long is met with the cold fist of the Soviet authorities. Lyrics have to be authorized by Kafkaesque procedures, with Dylan-esque ballads re-marketed as simple songs of the proletariat working class. However, there’s a frisson of excitement, an erotic charge even, in knowing there are boundaries that cannot be crossed, and for artists to tiptoe as close to the line as possible.

The curious thing is in the late Soviet period of the film, the establishment began to mellow, allowing the emergence of Russian rock into the mainstream as Perestroika reared its head. Here, if you jumped through the bureaucratic hoops, the authorities permitted artistic license. But today is Russia heading in an opposite, more repressive, direction? The Leto of the title, which translates to “summer,” might mark this a sort-of high point of Soviet popular culture that later gave way to the autumn of the regime and then the wintry period of post-USSR contemporary Russia.

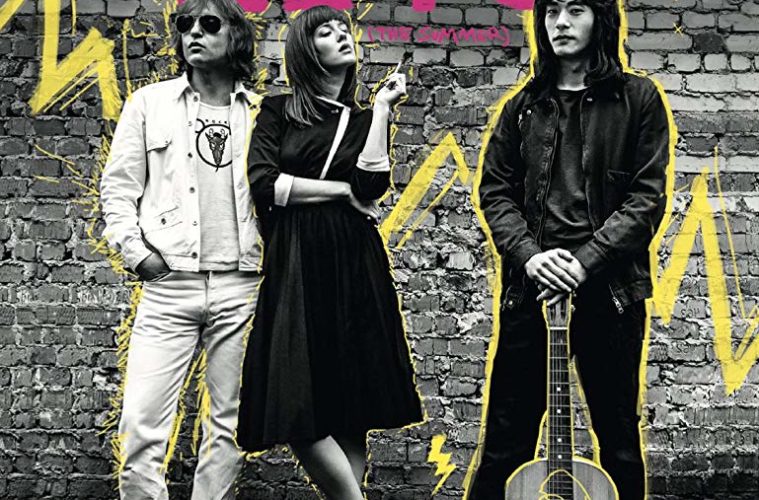

The story centers on the rise of Kino, a post-punk outfit who became one of Soviet rock’s most significant bands. Led by coolly dressed Viktor Tsoi (Korean-German actor Teo Yoo, remarkably in his first Russian-language movie), he’s supported by an old-school blues rocker Mike (Roma Zver, himself a singer with the band Zveri) who gives him the chance to embrace the influence of western artists from Lou Reed to Bowie, Talking Heads and Bob Dylan. The irony is the Soviets might never have had home-grown rock successes without the renegade artists of the West.

Neither, however, are the pivot of the film, which really is Mike’s young, sidelined wife Natasha, played in a regularly scene-stealing performance by Irina Starshenbaum. The film is notionally based on her memoirs, and Starshenbaum carries a casual melancholy as she begins to realize the rebellious streak in her rocker friends is found in her too.

Serebrennikov has a number of electrifying musical sequences, both in the diegesis of the film and outlandish imagined fantasies. One of the best is on a public bus where riders start belting the chorus to Iggy Pop’s “The Passengers.” Another is a rehash of Mott The Hoople’s “All The Young Dudes,” now retuned as a moody elegy to the period. It’s complemented with nifty intertitles and sometimes the black and white film stock changes to color. While these sequences are impressively choreographed, it retains a vital coarseness, and reminded me of the films of John Carney or Lukas Moodysson’s We Are the Best!, which can only be a good thing.

Leto sometimes comes across as a film a bit too pleased with itself, but it’s clear Serebrennikov wants his audience to taste the experience of the post-punk Soviet scene, to smell the sweat, to witness the ecstasy of a new track coming together–not to take his movie as a historical document. That’s why there’s a censorious Greek chorus-type figure listed in the credits as “Skeptic” (Aleksandr Kuznetsov), whose role is to talk to camera and say “this didn’t happen.”

Certainly anachronism abounds in Leto, but perhaps the director is taking on the Russia tradition of “vranyo” there, a term meaning “I know you know I’m lying,” as if to say despite the contradictions, “there’s truth to what I say.”

If only we could ask the director himself.

Leto screened at the 2018 San Sebastian Film Festival.