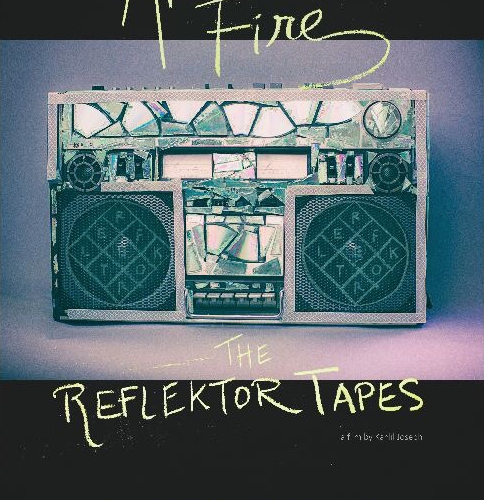

A list of things The Reflektor Tapes comes close to being but doesn’t quite end up as: a concert film stitching together Arcade Fire‘s work on a worldwide tour supporting their most recent album, Reflektor; a travelogue of said tour; a sense-memory visual essay tracing the years-long life of songs, tracing from hashing-out and recording to a presentation for thousands of screaming, jumping fans; a channel-futzing sonic exploration of song structure; a look at the making of a highly anticipated album; a study of the creative and romantic partnership between band leaders Win Butler and Régine Chassagne; a voiceover-supported glimpse into their thoughts on creative processes, influences, love, and the course of their lives; and a cultural document of Haiti, the country from which Chassagne hails and to which Arcade Fire bear a strong connection.

The film that resulting from this hodgepodge of approaches, possibilities, and creative stamps is a hyper-active Frankenstein monster, veering from one to the next at an always-rapid pace and rarely with a taste for proper transition. As directed and partially cut by Kahlil Joseph, assembled with the editing work of Matt Hollis and Daniel Song, and shot by Lol Crowley, Autumn Cheyenne Durald, and Malik Hassan Sayeed, The Reflektor Tapes uses the skeleton of a concert film — complete with an encore-of-sorts and post-credits bow-of-sorts — while attempting a meatier document by journeying down the thought-driven rabbit hole of where certain songs and ideas emerged from — to some extent. It’s ultimately ineffective as the latter, having relegated much to vague generalizations — Win says a trip to Haiti and experiencing the country’s creative side helped breed “a new way of thinking about rhythm and thinking about music”; this is about the furthest we’ll go on that front — yet is consistently different and daring as an entry into the risky territory that is the former. Oddest of all is that the constant jumping back and forth between onstage and off makes them inseparable from one another; while its moments of shining beauty aren’t dulled, the feeling that a better movie is lurking somewhere in this ocean of ideas nags from first moment to last.

If you’re an Arcade Fire fan who can tolerate some of their worst tendencies — e.g. cases of flat-footed lyricism and embarrassing self-seriousness, both of which are present here, because, boy, “Porno” does not click without its synth beat — it almost goes without saying that basic pleasures are to be found amid the scramble. Yes, watching these expert live performers energetically work though songs that you enjoy is a nice way to pass some time. Yes, the colorful widescreen compositions rank among some of the best footage of them that’s ever been shot. Yes, separating vocal harmonies to explore how husband and wife complement each other, particularly on last-resort romancer “Afterlife” is lovely, even if you’ve already heard the actual song a hundred times; the same goes for watching them discover complex arrangements in the studio. (I’ve no good idea why the best scene involving either of those was left on the cutting-room floor, though.) Yes, “Haiti” and their performances of it both remain perfect.

Yet it’s telling that The Reflektor Tapes’ more complex pleasures always hint at a smarter film. Joseph’s concert footage shuffles between various performances in various venues, and, having been captured with different shooting formats, color temperatures, film stocks, and aspect ratios, become indecipherable from the other, suggesting a creative unity and consistency that seems otherwise impossible on a year-long, globe-spanning journey. The intimacy so obviously striven for is best played with at one particular moment: a minutes-long, black-and-white close-up on Butler and co. performing a particular song gives the impression they’re playing in one of their “secret,” small-venue shows shows, only to be immediately followed by a black-and-white wide shot collapsing them within the same frame as a stadium-sized crowd taking in that same song.

Many thoughts can spring from this quick, easily missed bit of editing work. What does it mean to slave over a song that eventually grows into a massive celebratory anthem? How do the inevitable differences found in every performance change its character? Do we ever get close to understanding the people making these songs, or are we getting all we need and could ever have? What are they thinking at these moments, and are Tapes‘ digressions a representation of that? (Other questions, such as “What if the camera? Really do? Take your soul? Uh, oh, no!” on “Flashbulb Eyes,” and other signifiers of the band’s creative intent, such as the whining guitar on “Normal Person,” don’t necessarily improve in this setting, but other, better aspects of either track stand out when we can see them being performed.) Most satisfying, in retrospect, is how the sequence manipulating “Afterlife” on a channel-by-channel basis eventually rhymes with these segments, in its placement not necessarily answering any of the above questions but supplying more to consider on those fronts. If there aren’t many personal revelations to be found in The Reflektor Tapes — or if what’s present in that department is a bit eye-rolling, e.g. Win Butler saying “People have false expectations of what love is, you know?” over the sight of black-and-white Haitian vistas — these at least suffice as intimations. In certain cases, that’s preferable.

I’m nevertheless singling out two spots in a feature-length film. Outside these noteworthy signs of intent, its structure is at once too manic and predictable, altogether piecemeal in delivery, to harmonize its many pieces of content and forms of presentation. (I’m sure just one more replay of the color-saturated time-lapse skyline would convince me it serves a real purpose.) Those moments when Tapes‘ sense of shape peeks through — a standout being the way Chassagne discussing her heritage leads into footage of Haitian Carnival, a noted influence on the group — imply that a comprehensive work could be culled from however much footage Joseph shot, ultimately frustrating all the more as a result. (Not for nothing that its montage- and sensory-heavy attempts at a close-quarters portrait brought to mind Miroir Noir, a largely forgotten document of Neon Bible’s production that, whatever its own flaws, has a few moments which outshine anything here.)

It’s to The Reflektor Tapes’ credit that I’d have sat through something a bit longer — at 75 minutes, this is just about the same length as Reflektor; if one removes the end credits, which are set to the title track, Joseph may have directed the only album-centered film that’s shorter than its subject — if only out of hope that something more piercing would eventually come to light. (Or perhaps I just want to see more of Régine and Win backstage — yet another thing that was filmed and excised.) As an admirer of Arcade Fire’s music and, more personally, as one who’s found great beauty and comfort in some of the songs prominently featured, it’s frequently engaging as viewing material. Being a viewer who not only seeks a greater impact than what I was given, but, more specifically, also feels that their dynamic, sweeping sound very much deserves a cinematic accompaniment, it’s far less concrete as an experience — if still one I’ll gladly revisit out of curiosity and, for better or for worse, a desire to again grasp its fleeting successes.

On a final note, I feel it’s necessary to note the conditions under which this was viewed. Critic Mike D’Angelo has said that, in the world of online screeners sent out to critics for review purposes, “There are only two platforms: Vimeo and Bullshit.” The Reflektor Tapes was viewed via bullshit, specifically Shark Player, an insanely compressed window with logos burned into it so as to ensure that, as the accompanying email explained, “any pirated version of the content can therefore be traced directly to [the critic].” (See here and here for an example.)

Even if the central, worst watermark wasn’t a result of the player’s policy — oh, how well those black screens acting as transitional effects work with “PROPERTY OF ARCADE FIRE LLC.” emblazoned across them — I feel compelled to ask: who the fuck do you think I am? If you don’t trust me with the film, don’t bother sending it, and certainly don’t put me through the process of watching something that looks like it was transferred from a decades-old VHS tape. (Image-quality differences between the supplied film and online clips — that is, footage virtually anyone with an Internet connection has been able to watch for weeks — are night-and-day.) Imagine this scenario in other professions. No person in their right mind would ask a food critic to review a salmon steak that’s been cooked at the wrong temperature and sprinkled with dust mites, and the chef who prepared it almost certainly wouldn’t be pleased if that were the case. I suspect that this is not how Joseph, Crowley, Durald, and Sayeed — or anyone who worked hard on the images in this film — wanted their work to be experienced, and I know it negatively affected my perception of the endeavor.

The Reflektor Tapes premiered at TIFF and will enter a limited theatrical release on September 23.