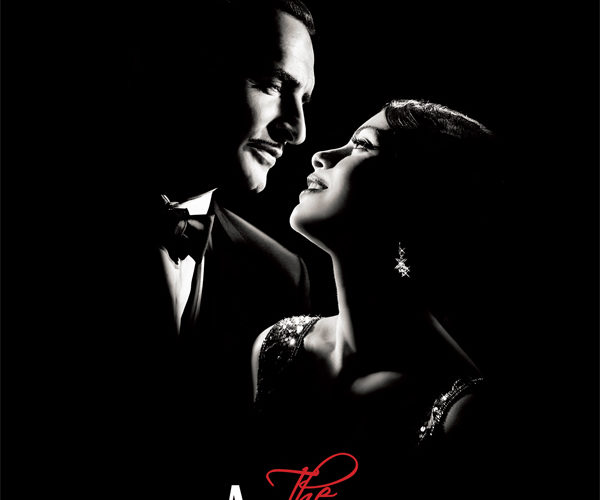

Whether it be The White Ribbon, Control, The Good German, Tetro or In Search of a Midnight Kiss, there have been a number of films that have utilized the black-and-white aesthetic in recent years, to mixed results. We’ve seen some use it as no more than a gimmick and others succeed in grasping the beauty of the monochrome, but director Michel Hazanavicius has taken it a step further with his sure-to-be Oscar darling The Artist.

Following George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), a silent film “artist” at the top of his game, Hazanavicius’ approach includes everything one would find in a film from the 1920s. Presented in 1.33 aspect ratio, audible dialogue is exchanged for title cards while the entire production is complimented by a swelling orchestral track.

Dujardin exudes the charm required for such a role: a handsome figure that conveys palpable emotions with a simple glance. Upon meeting Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo), a fan and aspiring actress, at the premiere of his latest Hollywood hit, he becomes infatuated with the woman. She finds herself auditioning for his next production, and after getting the part, she is reacquainted with Valentin, leading to two of the most charming sequences in the film.

Blocked by a passing prop, with Valentin on one side and Miller on the other, they can only see each other from the waist down, cloaking their identity. A back-and-forth playful game of dancing occurs and it is these moments of completely visually storytelling where Hazanavicius and his film shine. After realizing who the other is, the scene must be shot and there is another brilliant implementation of silent film constructs involving multiple takes.

Blocked by a passing prop, with Valentin on one side and Miller on the other, they can only see each other from the waist down, cloaking their identity. A back-and-forth playful game of dancing occurs and it is these moments of completely visually storytelling where Hazanavicius and his film shine. After realizing who the other is, the scene must be shot and there is another brilliant implementation of silent film constructs involving multiple takes.

As charming as these moments are (and the film is peppered with them), the story is unfortunately rote. Miller begins her rise to the top, through an example of escalating credit rolls, showing the correct way on how to execute a montage. At the same time, Valentin fades into the background as he refuses to do “talkies,” and the aftermath of these similar situations occur for much of the second act.

I understand the intention to strip the narrative down to the basics, in order to match the inherent nature of a limited silent film. But when your lead character hits a roadblock that lasts an entire reel, it makes for a sluggish time. Instead of forward momentum with him, we explore the cinematic period at the time, with the birth of “talkies.” This is welcome, but the story never moves along as quickly as the opening would have us guess.

With this radical invention of diegetic sound forever changing Hollywood, we take a note from the classics Singin’ In The Rain, Citizen Kane, A Star is Born and many others, enabling a dose of film history, which occasionally overcomes the loose narrative. In strictly Oscar race terms, this is a feel-good package, inoffensive and perfectly suited for The Weinstein Company’s elaborate campaigning.

With this radical invention of diegetic sound forever changing Hollywood, we take a note from the classics Singin’ In The Rain, Citizen Kane, A Star is Born and many others, enabling a dose of film history, which occasionally overcomes the loose narrative. In strictly Oscar race terms, this is a feel-good package, inoffensive and perfectly suited for The Weinstein Company’s elaborate campaigning.

Spot-on soft lighting from cinematographer Guillaume Schiffman, a rousing score from Ludovic Bource, a fitting supporting cast (including John Goodman chewing scenery as a studio head) and top-notch production from the rest of the crew makes for a festival darling. As for an austere, lasting piece of work, it would be too precocious to immediately deny The Artist, but I can’t help the feeling this more of a rare, but minor exercise to show something like this can be pulled off.

The Artist will hit theaters on November 23rd, 2011.