Finding solace in constancy – times of turbulent change and ever-shifting paradigms of social expectations can be a source of intense stress – and the desire for a firm and steady track in life can be overwhelming. The problem with this idea is that the very essence of growth and betterment lies in change, and so the act of avoiding the difficulty of evolution can turn constancy into inertia. Without the energy and courage to seek something better, you may find yourself in a terrible situation purely out of comfort in a lack of motion.

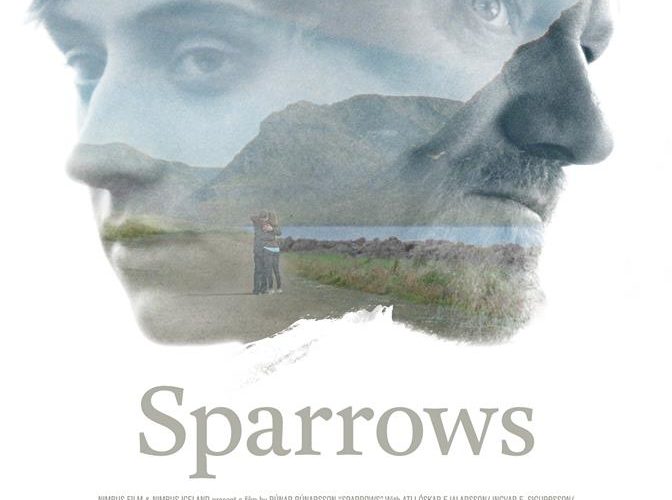

This is the existentially mortifying idea at the heart of Sparrows, the newest film from Volcano director Rúnar Rúnarsson. Ari (Atli Óskar Fjalarsson), a teenage choir singer in Reykjavik, is forced to move back to his rural hometown with his estranged father after his mother follows her new husband to Uganda, the first step in a trip that will take her to many underserved countries, presumably as part of a humanitarian effort. His father, Gunnar (Ingvar E. Sigurdsson), scoffs at his ex-wife’s new lifestyle, her marrying of a foreigner and desire to change the world. Dissolute from his failed marriage and the loss of his house and boat, Gunnar spends his days in a dilapidated cottage drinking and partying with his friends, spending dinners and some early evenings with his elderly mother, Ari’s grandmother, the only person who seems to understand and respect the energy that Ari’s mother possesses.

Forced to work at the fish processing plant in town and with only the haziest recollection of his time spent in this area as a boy, Ari spends his days slowly drifting through a life that was thrust upon him, abandoning any sense of agency. He breaks into his old house to avoid his father’s arrest development lifestyle, and mopes around on the outskirts of a group of kids his own age. His stupor is unchallenged by his father, who shrugs off the words of warning lobbed at him by his own mother. Life has begun to stand still for these people, and the only voice of reason and progress and hope in their lives belongs to a woman who is facing the end of her own life.

Rúnarsson shoots these scenes of torpidity and inert social collision with a static camera, changing focal length more than changing shot composition. This helps to both highlight the beautiful, misty landscape of the northern Icelandic setting and the stupor of those who inhabit it like ghosts. There is an ever-present stillness in the air, and the inhabitants of this town seem to have taken this to heart. Even as Ari seethes with a sense of righteous anger over his circumstances, he is tamped down and reined in by those around him.

For all the excellent work that Fjalarsson does at communicating Ari’s disaffection and unhappiness while remaining sympathetic and compelling, it is Sigurdsson’s work as his father Gunnar that deserves the most attention. A man composed for pain and uncertainty, he turns what could be a brusk, loathsome character into a figure worthy of true empathy. Every time he shows a sign of pulling himself out of his torpor, one cannot help but hope that this is truly the time it takes hold. His utter lack of effectuality and understanding is at once pitiful and easily understood. When he feints at being a better father, it is hard not to hope that Ari meets him halfway, allowing them both to prop the other up and out of their emotional quagmire.

Yet the most important character for understanding the meaning and purpose of this story is probably the sun. Near or above the arctic circle, the sun never sets in the summer. Every scene is awash in a grey-blue light that makes the specific time of day in each scene impossible to determine. Time between scenes is likewise difficult to discern. How long has this bender lasted? How late did this character sleep in following a night of debauchery? Is this party roaring into the morning, or just getting started in the early evening? It gives the story the feeling of being locked in a single time, the constancy of the sunlight allowing the very concept of time to lack any meaning. Lacking the natural rhythm of light and dark, it isn’t hard to see how life could be allowed to stretch into an eternal miasma of youthful insouciance.

What one takes from this movie, and how one eventually lands on the subject of its quality, will likely depend on the final gut-wrenching decision that Ari has to make. Having allowed himself to succumb to some degree to the lifestyle of this town, and having scene the depravity and blackness at its heart, he makes a moral choice that is wholly amoral. The damage has been done, but it can be contained with a lie, one that robs someone of any agency – just as he was robbed of his – while at the same time sparing them the darkness of existence. The film, rigid in its stylistic naturalism and lacking any non-diegetic music, does not tip its hand as to its feelings regarding the choice Ari makes, and it could be said that the true final act of the film takes place in the viewer’s mind, while they struggle to comprehend those final moments.

Even Ari doesn’t seem to know what to make of his choice, and of course there is no one around to counsel him or guide him. He is alone at the end much as he is alone at the beginning, a scared young man standing on the brink of adulthood, alone and confused, longing for even the pantomime of parental or adult attention and protection from a life he never asked for.

Sparrows allows us an unsparing glimpse into a life we might never know ourselves, and when it closes the curtain on the scene we are left only as enriched and moved as we allows ourselves to be. The final verdict on this film is like a choose your own adventure novel, where the choices are to turn away in disgust, or meditate in silent, appalled ambivalence. To a certain kind of audience, the latter option will make this a film well worth seeking out.

Sparrows premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.