To say Southcliffe gets off on the wrong foot would be to realize that beyond the seemingly well-orchestrated images in its opening minutes, there already lies the signs of something deeply systematic and portentous: an oppressively grey color palette, “moody” exteriors of a small English town highlighting its empty rural plains during a seemingly eternal dusk, only to then be interrupted by shots ringing into an old lady. Seems menacing and atmospheric? Well, when — only a few minutes later — we see the contrast of this violent action with the shooter embracing his own frail mother in his home, it reveals not only its non-linear narrative structure, but also the cheapness of it that will ensue over the next three hours.

By following his debut feature Martha Marcy May Marlene with, surprisingly, a miniseries — a format that, by its very nature, entails a bigger story to tell — director Sean Durkin has trickier terrain for smoothly weaving in and out of time, which despite the issue of his debut’s overall machine-like nature, at least made it appear to be the work of a seasoned pro. Yet the miniseries requirement of at least a three-hour runtime mercilessly elongates a pointless series of juxtapositions and ellipsis: while Durkin seems a victim of his script (by Red Riding Trilogy scribe Tony Grisoni), the clunky, heavy-handed flashbacks and flashforwards ultimately bear the sign of someone who believes too much in his material.

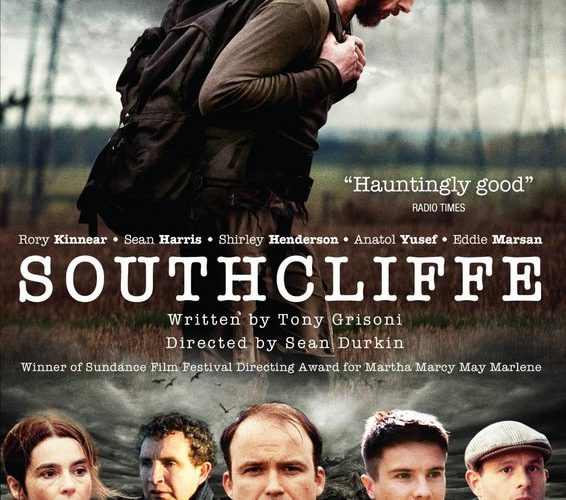

The strands shred up and re-arrange throughout, beginning with our shooter: a young soldier, Stephen, played with Sean Harris’ bearded, bird-eyed thousand-mile stare, at no point seemingly capable of coming off as an introverted weirdo prone to a violent outburst. Next are the family of his victims, including the couple Claire (Shirley Henderson) and Andrew Salter (Eddie Marsan), the former a social worker caring for Stephen’s mother, and whose daughter dies at his hands; Paul (Anatol Yusef), a cheating, unappreciative husband and father who of course only learns to appreciate his family once they fall victim; and, lastly, David (Rory Kinnear), a television host returning to his hometown of Southcliffe only to face turmoil over ethics once getting deeper into the incident.

But all these characters, while sympathetically performed by their skilled actors, are simply clamped too tightly in the vice of the conceit. Anatol Yusef, in particular, is the victim of multiple smash cuts, his character only able to be dealt with through ellipsis whipping us from the middle of one pathetic and despicable act to the next, as if so much as empathy towards him is some impossible act for the filmmakers. It’s a strategy which makes this awkward morality tale deterministic rather than considered.

And perhaps this is why Southcliffe’s strategies don’t seem to land with any grace, as their intention is always a sudden impact — harsh cuts before violence for easy contrasts. But this becomes an issue in that these smash-cuts are acts of violence themselves; while not seeing the actual aftermath of bullets ringing into a car or a suicide attempt would seem to be making its humane intentions ostentatiously clear, the problem is that the offscreen violence simply becomes another pattern. When our anticipation is that it’s eventually going to abruptly cut away — and it always does — it rewards in a fashion similar to the way splatter-fests play to gorehounds.

The source of only more formal suffocation — and to, unfortunately, drag in the name of a great, humane director amidst its glib art-film quotations — is its use of the car as a primary location, undeniably recalling Abbas Kiarostami. Yet unlike his motif of the vehicle, the interior of a machine, while enclosed, still manages to articulate a relationship with the outer world; a camera outside the windshield is not just a functional medium or two-shot, but, rather, opening the film up. In Southcliffe, however, the constant framing behind the driver’s head — leaving a marginal view through the windshield, except of course to “artfully” frame the middle of a beating — only encloses the film more, separating us from the characters even if we’re claustrophobically trapped with them.

But that Southcliffe is playing at the Toronto International Film Festival in its entirety is no surprise, as it ultimately comes in a trendy film festival package combining British miserablism and tired fractured-narrative tricks. The package itself is all design, a stylistically “correct” box with nothing in it.

Southcliffe screens at TIFF on September 6th, 7th and 13th. Watch the trailer above.