Directed by Mahnaz Mohammadi (her feature fiction debut) and written by Mohammad Rasoulof (a renowned Iranian filmmaker), Son-Mother is about exactly what its title infers. The labels themselves are somewhat subverted, though. Split into two halves with interstitials, “Son” actually centers on Leila (Raha Khodayari) while “Mother” stars Amir (Mahan Nasiri). The reason for the switch is that these sections prove as much about who’s not on-screen as who is. In a conservative culture balanced upon reputation, these characters are ultimately forced to sacrifice their own happiness in the moment for the other’s potential future. “Son” is therefore about what Leila does to protect her boy while “Mother” concerns what he must endure to return the favor. And hope for a happy ending seems forever like fantasy.

The drama is born from tragedy: Leila becoming a widow. It was okay to work a factory job and raise two kids when her husband was alive because he brought “social” stability. His absence therefore sparks rumors that don’t need a factual basis to ruin her name. All it takes is one person discovering the employee bus driver Kazem (Reza Behboodi) proposed for gossip to spread like wildfire. The longer things go without an answer, the more salacious and damning the talk becomes. Once deemed a tease (or worse), she’s transformed into a vulnerable target for co-workers worried about losing jobs amidst an impending strike to pounce on. The patriarchal rules of Iran make her beholden to one man when married and every single other man when not.

While marrying “solves” this abuse (by reinstating a reputation that never should have been slandered in the first place), it would also guarantee having to let Amir go. Because Kazem has a daughter soon to be of marrying age, his reputation would be ruined if he let her co-exist in cramped quarters with a boy Amir’s age. It doesn’t matter that he says he’d love his stepson as his own because you truly can’t trust any man in a society bred upon lechery and male superiority. Having their mutual friend Bibi (Maryam Boubani) vouch for him also proves meaningless since it could all be a lie. Leila chooses to remain single and not betray her son, but the world surrounding her is rendering that choice impossible to sustain.

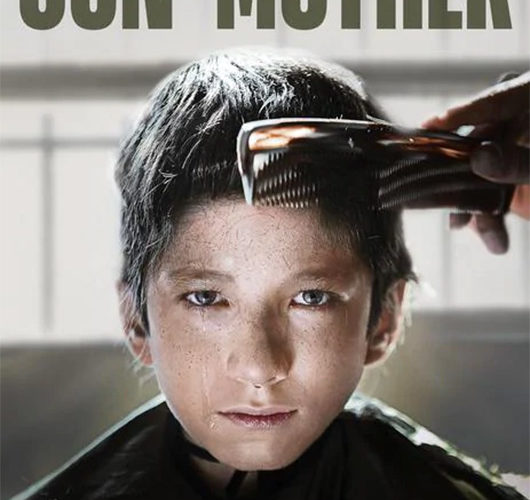

And what about Amir? If Leila does decide to marry and improve her and her daughter’s lot while holding onto the hope he’ll join them later, what will he be asked to do? The best-case scenario is three weeks to butter Kazem up into saying, “To hell with rumors.” The worst is three years until his daughter can be married. Since Leila has no family to care for him in the interim, Mohammadi and Rasoulof create a wild solution by way of having Amir fake deafness to earn room, board, and education at a school where he doesn’t belong. This is the level of desperation in which Leila finds herself—lying, cheating, and risking the sort of exposure that sees him placed in an orphanage before her arms.

The lives of mothers and children in Iran are thus rendered forfeit by the men coercing them to conform to their selfish wants and desires. When a good man like Kazem is helpless to buck that trend, what chance does anyone else have? Mohammadi isn’t afraid to ensure we know which gender is to blame either as Leila’s boss feigns charity via an unspoken desire for her and a co-worker treats her like garbage because one word of slander is enough to place him in the right without the need for corroborating facts. And no amount of confidence or courage (don’t forget opportunism too) can render any so-called “heroes” exempt from finding their hands tied once a situation they manufactured leaves their control. Winners simply don’t exist here.

Kudos to Khodayari and Nasiri as they nail the mix of futility and delusional optimism necessary to keep their characters on the edge of self-sacrifice. The defeat in Leila’s voice whenever she attempts to push Kazem away is heartbreaking because we know she knows what he can provide her family for the price of her son’s present. The anger in Amir’s expression is just as potent because he’s determined to achieve the endgame he’s promised. And Behboodi also delivers a poignant turn considering his internal war between conformity and morality. His Kazem is so good with Amir and yet he’s powerless to keep him under wing. Eventually the lies they tell each other to construct their elaborate happily ever after become the lies they tell themselves.

Son-Mother premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.