Based on lead actor Adrian Schiop’s fictionalized biography, Ivana Mladenovic’s Soldiers. Story From Ferentari shows a world of poverty and futility possessing few avenues of escape for those born within. Schiop’s character Adi arrives at the Bucharest ghetto known as Ferentari to study its people’s music of choice: manele. He’s researching the sound for his PhD thesis, the recent dissolution of a relationship at the behest of his ex-girlfriend providing the room to uproot himself for the work. But while this setting provides cheap rent—thanks to sharing an apartment with young translator Vasi (Cezar Grumarescu)—it also holds the unpredictable danger of desperation. Adi finds himself surrounded by unemployed hustlers and ex-cons using fear to satiate their vices. And it risks consuming him.

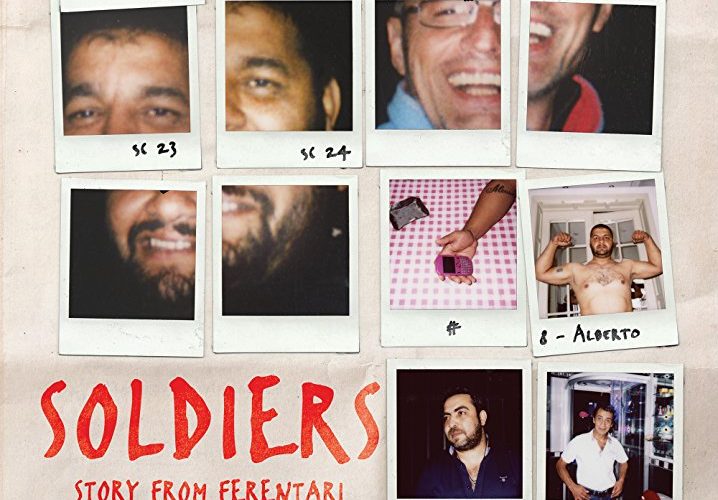

The film is his meandering journey: an optimist gradually trapped within a world devoid of optimism. Adi is a soft-spoken intellectual, unassuming and genial with enough charm and innocence to win over those who look to take advantage of him. One such example is the psychologically damaged Alberto (Vasile Pavel)—a man with a good-natured smile that brings you closer before his temper instantly replaces it upon not getting his way. Adi buys his kindness with a beer, sealing a deal for Alberto to become his local guide amongst the corrupt managers exploiting young kids blessed with voices that sustain manele as a moneymaking operation. Working for a Mafioso named Borcan (Nicolae Marin) provides connections, but what starts as a professional relationship for alcohol and smokes soon evolves.

Loneliness gets the better of them and they let their guard down as a result. Adi is heartbroken; Alberto a victim of oppression who has compensated by becoming an oppressor himself. The latter opens up about his time in jail from the age of fifteen and the sexual abuse that went on. He would never call himself gay—merely an opportunist who realizes the gender of he or she that gives him pleasure doesn’t matter behind closed doors. So Alberto’s advances towards Adi are rooted in companionship and past feelings of safety and security bred in prison by his assailants’ “protection.” Adi lets him in, seeing this other side of the brute those around Ferentari know. But as soon as he does, Alberto’s destructive nature is revealed.

Suddenly the manele thread is completely thrown out the window where it doesn’t present a scenario able to anger Alberto. What replaces it is this domineering romance wherein the man quick to declare his love ensures the other is aware it doesn’t come for free. Alberto is the one who desperately needs Adi—his embrace the only escape from a cruel fate that he’ll probably ever experience. But his only examples of “love” come from transactional relationships. In his mind his love costs money. So he demands payment for his affection, something Adi provides first as a way to keep his guide happy and second because of necessity. Their dysfunctional love ultimately becomes their ruin. Their sexual lifestyle isn’t accepted in Ferentari and their single-income economics proves unsustainable.

Mladenovic portrays these truths with little interference and little desire to craft something more than the very human tale contained within. It’s so slice of life that you have to wonder whether the enterprise would have been better suited to documentary. With so many non-actors and the poverty of Ferentari so blatantly on display, a glimpse at the real tragedy endured might feel more raw and imperative. I won’t lie and say I kept waiting for Adi’s thesis to come back into focus. I kept waiting for Borcan to play a bigger role than abstract boogeyman looming above to affect their existence. With all of that fading away into the background as motivational excess, it does become hard to truly invest in the abusive drama that remains.

The reason stems from both characters being sympathetic. While Alberto is obviously the predator, he’s become one thanks to a devastating history. He’s a product of the very poverty that imprisons him now. He can’t get a job without proper ID, but he can’t get proper ID without going to those who’ve disowned him for what he was forced to do in jail. And while Adi is the obvious victim, you can’t deny his charitable instincts. He’s positioned to know this man as more than his circumstances. He sees Alberto as deserving a second chance and someone who does have a good heart if only he let it shine brighter than the dark cloud of tempestuous rage created to survive. Leaving isn’t easy because their love is true.

Soldiers therefore becomes a trial of endurance as Adi and Alberto’s love continues to grow stronger in direct correlation with the reasons it must remain secret. We wonder if the former will finally say enough is enough and whether the latter will move from verbal abuse to physical as a means of keeping him like a piece of property. All the while Mladenovic cuts to vignettes of Ferentari and its deplorable conditions to give a sense of place. But where these would prove effective in a documentary, they take us out of the heavy drama of this specific romance seemingly going nowhere. And while there’s honesty to everything with the performances and character trajectories never feeling false, it’s tough to sustain the necessary attention to reach its end.

Soldiers. Story from Ferentari premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.