America isn’t the only country with a portion of its population rejecting refugee clemency (although it’s the most high profile due to international stature, economic wealth, and so-called Christian charity). It’s also not the only one blinded to its hate when confronting the matter. Because that’s what it is to look down on someone worse off than you: hate. Blaming immigrants for “stealing” jobs and “ruining” neighborhoods exemplifies resentment. Just because your community backs this thought process doesn’t make it any less a product of bigotry, racism, and baseless entitlement. Suddenly citizens sympathetic to these outsiders struggling to survive on a basic human level are labeled traitors and made into enemies themselves. Soon enough life becomes “us versus them” until even the righteous must fall prey to desperation.

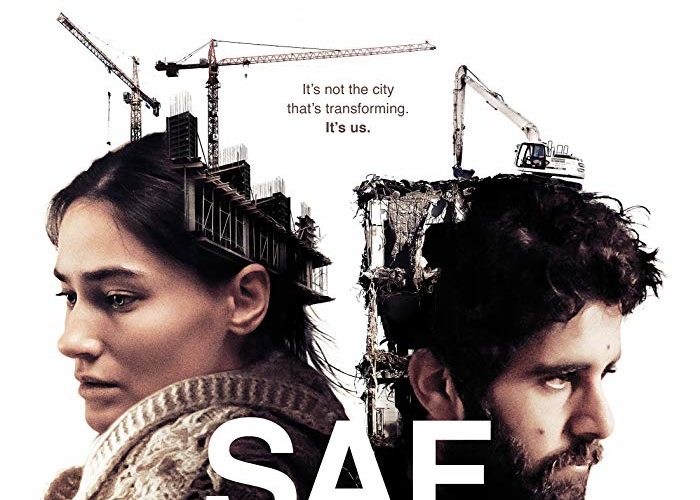

It’s this unfortunate reality that lies at the back of Ali Vatansever’s Turkey-set Saf. He introduces us to Istanbul’s Fikirtepe district, an area in the midst of an extreme gentrification-fueled overhaul displacing those who’ve lived there their entire lives. Add an influx of Syrians using the abandoned buildings that are sold but not yet razed for makeshift homes and you’ve got a wealth of poverty-stricken folk with nowhere to turn while giant skyscrapers are erected upon a graveyard of history. Who is forced to work demolition and construction? Those same people pushed out to make it happen. And when they prove too prideful to actively help displace their neighbors? In come those immigrants more than willing to work for less in order to put food on the table.

What then is a man like Kamil (Erol Afsin) to do? Unemployed for too long, he has no choice but to apply for the business his community curses for what it’s done. He must also beg to win a job from them because he lacks both experience and the necessary license. His privilege as a native Turk is therefore what his employer is willing to take the risk on. They can pay Kamil the same low wage as a Syrian (Kida Khodr Ramadan’s injured Ammar) and also feel patriotic by keeping it “in the family” so to speak. While it’s no skin off their back, however, Kamil has walked into a veritable trap. His neighbors harass him as a turncoat, his coworkers a “scab,” and himself a hypocrite.

The latter is because of what he’s always been: kind, generous, and moral. Kamil is the type of guy to take care of his block’s “shared” garden by himself and still refuse to take extra vegetables than what is equal for all. And while this idealism was probably a reason as to why his wife Remziye (Saadet Aksoy) fell in love with him, even she can’t help herself from trying to get him to wake up and face reality. To steal this job from someone more qualified and responsible for feeding a much larger family isn’t therefore in character. While it eats away at him, though, the pressures crushing his resolve prevail. He can only witness loved ones becoming selfish and jaded for so long before following suit.

The first half of the film depicts this gradual devolution marked by a guilty conscience, personal disappointment, and heart-breaking assumptions. The second turns its focus onto Remziye as she’s left to learn everything that Kamil hasn’t told her upon his disappearance. She too had probably been someone unable to fathom what we ultimately watch her attempt — her second-guessing and refusal to follow through on cutthroat ambitions proving her anger is a product of the times more than her true identity beneath the stress. Remziye works as a maid for a rich woman (Ebru Ojen Sahin’s Mrs. Burcu) who also employs a nanny (Mihaela Trofimov’s Ivona) for her infant. And in a moment of greed she schemes to deport the latter’s Romanian immigrant to take on both jobs instead.

Vatansever shows how quickly we will let our own dire circumstances dehumanize those much worse off. The simple knee-jerk justification that we deserve something more than another because of where we were born or who we were born to can be an alluring excuse. “I live here and therefore I should be put first. I have a piece of paper that grants me certain rights you’re without, so why shouldn’t I let the authorities know where you are before you cause trouble?” It’s a slippery slope wherein too many of us find ourselves on the other side unscathed. To still be standing sows the seed that perhaps we belong there — a thought that emboldens us to fall further down a rabbit hole of superiority. Karma, however, never forgets.

As soon as you cross that line there can often be no turning back. To press pause on your humanity or compassion for a second is to risk losing it forever. Kamil is given multiple tries to combat the urge to be indecent like everyone else. He’s provided ample opportunity to turn around and do the right thing except for the reality that “the right thing” can sometimes be impossible to choose over “the easy thing.” It therefore proves devastating to watch Remziye put the pieces together to reconcile what she’s told happened against the man she thought her husband was. It’s only through that mirror that she can acknowledge her own missteps — her own cruelty dismissed with an indifferent shrug until finally putting herself in her victim’s shoes.

Saf proves an illuminating drama with relevant and resonant themes moving beyond its Turkish borders to our own. It’s populated by complex characterizations that exceed their seemingly two-dimensional surfaces (see Onur Buldu’s Fatih, a friend of Kamil and Remziye who talks loud yet avoids conflict) and two lead performances possessed by emotional depth and unforgettable moments of comprehension that sometimes arrive too late. Afsin propels the first half forward with his increasingly unpredictable anxiety while Aksoy carries the rest through an authentic progression from indignation to shame and ultimately to clarity. Theirs is a couple struggling to build a home without realizing their role in destroying the world around it. You can’t have one without the other. And unless we work together, we all end up with nothing.

Saf premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.