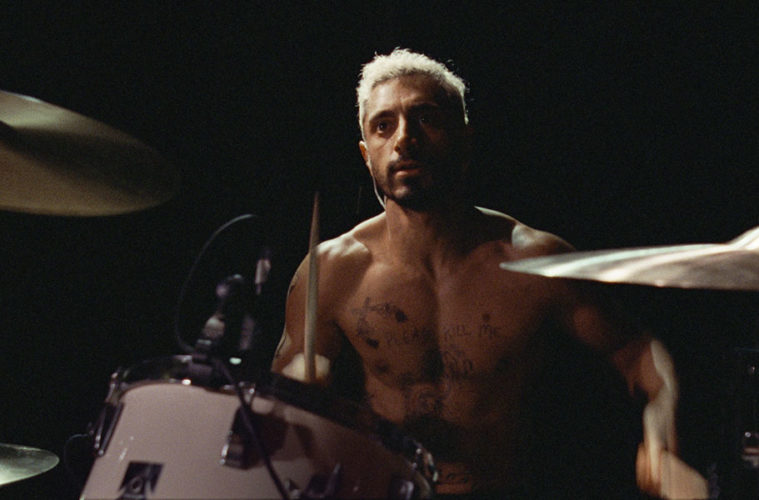

Sound of Metal opens with Riz Ahmed’s Ruben sitting at a drum kit while guitar distortions deafen us. Eventually, Olivia Cooke’s Lou starts screaming as his sticks connect for a steady beat until all hell breaks loose. We’re in this venue with them, the in-close camerawork proving Ahmed’s lessons paid off because he is in a groove and rocking out (not that he needed help on the second part considering his rap career as Riz MC and one half of Swet Shop Boys). With line drawn tattoos covering his chest, bleach-blonde hair, and that screaming, you’re probably assuming the after show will consist of booze and drugs before the visuals cut to a new day of health shakes and eggs in an RV. Appearances can be deceiving.

That’s when writer-director Darius Marder rips the rug from under his lead via an incessant ring. A day after that blistering on-stage performance, Ruben is left with a dull roar that underwater voices can barely penetrate. He goes back behind the kit anyway, hoping it’s temporary until the next morning delivers even less clarity. A trip to the pharmacy leads to a doctor’s appointment—a godsend considering their tour brought them to a state where they don’t know anyone—and he’s told the life he knew was over. It shouldn’t be about the sound he lost, but the sound he might retain instead. Only after another show ends with a panic attack, however, does he finally let Lou know what’s happening. That’s when the difficult journey towards acceptance and healing begins.

This is a very personal story to Marder and it shows in the intricate ways he uses sound to place us within Ruben’s plight. He and his brother (co-writer Abraham Marder) had a cinephile grandmother who went deaf from complications with antibiotics and subsequently petitioned theaters to subtitle films for the hearing impaired (Darius honors that with closed captioning for the duration). The director also grew up in a spiritual community led by a man whose philosophies helped define his life like the character of Joe (Paul Raci), the leader of a recovering addict program for the deaf. As such, the places Ruben is written to go take on an intensely emotional weight as memory, respect, and truth permeate te fiction on-screen. And Ahmed’s performance injects more of each.

Shot with a very intimate handheld style that reminded me a lot of Derek Cianfrance’s Blue Valentine (he’s an executive producer here and an original collaborator before his Place Beyond the Pines writer brought brother Abraham on board), we’re forever witnesses to Ruben’s struggle and desire to get back what‘s gone. As Joe says straight away, however, that line of thinking is destructive. To truly help this lost soul drowning in self-pity and fear, all connection to the past must be relinquished so he can rebuild himself anew in the reality he’s yet to face. That means Lou forcing him to go alone—a tall order considering where she and Ruben were when they met and how they saved each other from their personal oblivions.

He’ll have to also table the pipe dream of paying for a cochlear implant his denial won’t let get fully explained. All Ruben absorbs when the surgery is mentioned is a return to “sound” while the details of that sense fall into the silence. Because one of Joe’s rules is a refusal to treat deafness as a handicap—something “fixing” inherently does—Ruben must harbor that fantasy in secret while learning ASL (thanks to his enrollment in Lauren Ridloff’s grade school class) and becoming a valued member in this deaf community. The addictive mentality ruling him, however, won’t let him breathe in this brave new world if a door to the past remains open. This war within therefore risks ruining everything he’s gained for a chance that might never arrive.

The layers to this truth are many as we learn about Ruben’s history and recognize he must lose the constant from his life in recovery to recover from something else. How quickly he slides into old habits and self-harm is heartbreaking to us and Lou because him being unwell means her barrier from falling too is gone. Ahmed loses himself in Ruben’s descent, turning from violent tendencies to breathless contrition until even the character recognizes something must change. It won’t be easy, though. Especially not for someone too prideful to take the work Joe is giving him on faith. Ruben is a doer and quiet has never been a safe place for him. That’s why isolation is key to learning and why his continual defiance proves detrimental.

Marder does let optimism in, though. After the gut-punch of act one envelops us in this new world devoid of understanding (sign language is never subtitled and the impeccable sound design shifts from extreme loud to a sea of white noise), Ruben does excel. He’s working towards a reunion with Lou after all. The question is then whether he makes the journey as a deaf man made psychologically whole or a prisoner to what can never be again. Is his place in Joe’s world therefore authentic or disingenuous and if the latter, how irreparable will the damage prove? I’ll let the film provide that answer itself and simply say the conclusion is as devastating as the start with the bittersweet addition of hope to help us through the pain.

That pain is what sets Sound of Metal apart, though, so don’t assume its lasting power is a reason to avoid the film. It ultimately inspires. Knowing it can be used as a strength to endure isn’t something many writers are willing to embrace these days. Where others would have kept Lou as Ruben’s rock regardless of her own issues, Marder ensures she won’t fall prey to her boyfriend’s whims. Cooke might have a fraction of Ahmed’s screen time, but her character is crucial to the message of the whole. The same goes with Ravi’s Joe and the honesty that exists in revealing how saviors aren’t beholden to their saved. Love is transformative and what we needed to survive then isn’t always what we need to keep surviving now.

Sound of Metal premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.