Maria Theresia von Paradis was the daughter of Empress Maria Theresa’s Court Councilor and thus a young woman of standing despite the blindness that took her eyes before the age of five. Her father Joseph Anton and mother Maria Rosalia had the means to therefore teach her the finer things such as piano — a vocation to which she found expertise. The Empress allowed her a disability pension as financial assistance to help offset the strain of raising a daughter in the eighteenth century without prospects for marriage. But the pain in her eyes grew and every doctor hired to alleviate it only made matters worse. Franz Anton Mesmer became their last hope with his laughable method of healing via an invisible, odorless, and weightless magnetic “fluid.” It worked.

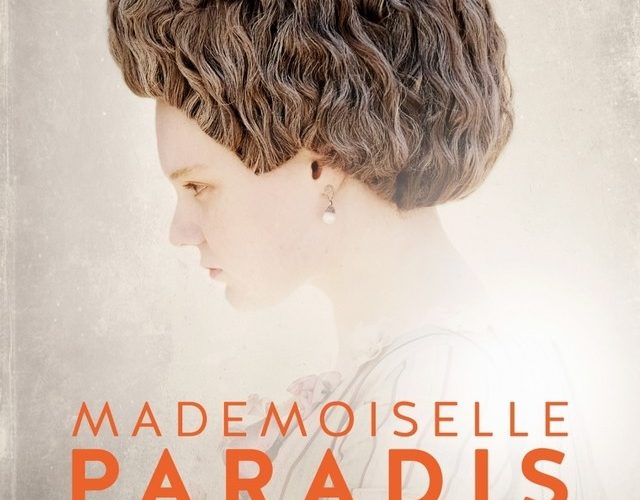

Paradis (Maria-Victoria Dragus) would eventually become a touring musician and composer who may have also been an inspiration to Mozart (she even learned under his supposed rival Antonio Salieri amongst others). But that success isn’t what makes her such a captivating subject. It’s the period of time with Mesmer (Devid Striesow) that intrigues because of the rumor and speculation surrounding her recovery not only from the pain, but also her blindness. She becomes a pawn in the aristocratic games of many including both Mesmer and her father (Lukas Miko): one seeking fame and a university position in reward for his success and the other a “normal” daughter who could be seen as more than a pianist in order to alleviate the burden she’d become. Her wellbeing became secondary.

It’s this theme of opportunism that runs rampant in Barbara Albert’s Mademoiselle Paradis, scripted by Kathrin Resetarits from Alissa Walser’s novel Mesmerized. We watch as a young girl so attached to her mother (Katja Kolm) that she won’t let her go upon arriving at Mesmer’s home turn into a headstrong woman imbued with the independence she’d never before been afforded. She was given a new identity through her treatment, the faint return of sight (shadowy shapes on bright lit backgrounds) allowing her mind to see as well. No longer was she merely the blind girl who plays piano. She was also a person now. If only she could have known the miracle of sight would turn her into more of a “freak” than when she was without.

Initially paraded by her parents, Resi (short for Theresia) was later paraded by Mesmer. But while the former had selfish prospects in mind completely, the latter does actually care about her. Yes she’s ultimately a means to an end that his other patients never could prove — her sight catching the interest of the Empress’ famed doctor — but he still works to cure her. He doesn’t stop at amorphous blobs and muted colors; he continues her therapy to go even further. Resi becomes his favorite and many assume adulterous intentions as a result. Her father implies it too upon discovering her musical prowess had weakened as her eyes improved. Suddenly she no longer had his best interests in mind. Perhaps a blind savant better-suited Joseph Anton’s needs after all.

The film thus expands out to include the over-arching notion of ego and importance that consumed the elite in eighteenth century Europe. There are the parents quick to unload their “problem” on others as seen by the many unfortunate souls residing at the Mesmer residence. There’s the rampant entitlement both intellectually (Resi’s former doctors trying their best to trick her so they can call Mesmer a fraud rather than allow themselves to be failures where he succeeded) and sexually as shown by the silent yet devastating abuse conducted upon Paradis’ chambermaid Agnes (Maresi Riegner). We watch as a simple boy younger than ten is treated like garbage, his mere existence a strain on his servant parents, their “gracious” employers, and anyone forced to look at him in passing.

Albert places a cruel world onscreen despite its opulent finery. Her cast plays its characters as the monsters of greed, superiority, and vanity we believe them to be. Everything that happens to Resi is put through a lens of personal impact. What will legitimizing Mesmer’s work do to my reputation as a scientist? What will Resi’s sight do to her ability to play the piano and thus affect my livelihood? (After all, a lack of musical talent makes her less of a “catch” while the increase in sight risks her pension.) The only person who could begin to understand her limits (despite not having the courage to explain them and lessen his breakthrough) is Mesmer. To take her side, however, was to also welcome external whispers of infidelity.

All this pettiness and vindictiveness occurs before her eyes yet she sees nothing. Her blindness has made her a devotee to whoever is positioned to be her advocate. She followed her father through a revolving door of horrible men experimenting with nightmarish treatments and then followed Mesmer’s lead to be gawked at and called a hoax to her face. The only thing that ever gave Resi true joy was the piano because when she played all else faded away. The whispers of those talking behind her back, the blurry visages of beauty she still couldn’t quite experience in context beyond shape, and the heinous acts of men emboldened by their lack of witness: gone. One could say her ailment provided an innocence her social class couldn’t usually afford.

It’s a wonderful lead performance by Dragus with wild eyes rolling in pain before settling and an uninhibited smile throwing caution to etiquette. There’s an obvious frustration and sorrow to her Resi, a conflicted war between what she should feel and what she does. The best example of this is when she catches Agnes trying on her dress without permission. Her anger isn’t in the act as much as the deception. These two eventually become very close, the chambermaid’s position to help without requiring compensation a new thing for Resi. While all on her level haughtily talked about advantages and status, Agnes let her be an equal. In the end perhaps it’s better for her to be blind because it affords her this freedom to truly be herself.

Mademoiselle Paradis premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.