The year “2012” doesn’t appear at the beginning of Eva Mulvad’s documentary Love Child because it’s an era-specific story. No well-known international news headline is about to arrive as motivation for why Sahand and Leila fled Iran for the hope of sanctuary far, far away. The real reason for that date is perhaps even more heartbreaking when proven to be a simple case of timeline logistics. This is when the couple’s story starts, and we’ll eventually see more demarcations as it continues forward. What they believed would be a few months of exile in Turkey before the UN could review their case and send them somewhere “safe” quickly morphs into years. And the country threatening their lives remains a border away.

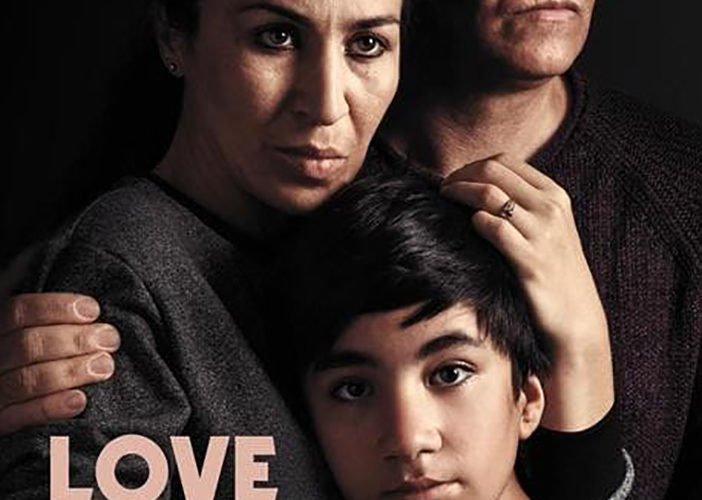

Sahand and Leila have become refugees because of the boy alluded to in the title: Mani. As they explain to the psychologist working their asylum case, Mani’s mere existence puts their lives in jeopardy. While he’s their biological son, he wasn’t conceived as a product of wedlock. Both Sahand and Leila were married to different people at the time and decided to keep the affair hidden to the point of letting her husband think the boy was his. It ultimately became impossible to keep up the lie once Mani’s home life grew untenable from domestic violence, though. In order to rescue him from that situation, they’d have to expose their crime. That’s how Iran sees adultery. Sahand’s sentence would be execution and Leila’s death by stoning.

Mulvad has a stunning amount of personal and private footage at her disposal to provide a sense of the terror they endure and probably will endure for the rest of their lives regardless of the conclusion. From the tearful phone call with Leila’s mother upon arriving in Turkey to their uncensored history told behind closed doors at the UN, it’s impossible not to understand how much fear is driving their actions. Both know in their hearts that a return to Iran will guarantee their deaths, but they also know there’s a chance the families they left behind will pay the price if they don’t. So they live with uncertainty and guilt above the anxiety-inducing panic born from checking the UN website for status updates ten times a day.

Can they start a new life in this purgatory? Turkey is in fact very good to them with new jobs and an apartment to call their own. They make friends, become a part of the community, and begin feeling comfortable despite still looking over their shoulders. In their minds they’re too close to home and simply resting at a way station upon a journey to Canada or the United States. But as anyone who’s lived through the past three years of the Trump administration knows, things don’t bode well as far as relocation is concerned if it takes too long for Leila and Sahand’s refugee status to be granted recognition. They’re fighting against a slow bureaucratic system and now a ticking clock they’re not even aware exists yet.

Love Child‘s best feature is Mulvad’s choice to never interject herself into their lives. The camera is a fly on the wall capturing good times and bad with a wholly objective eye. She picks which moments to use (birthday parties, squabbles, screams of profanity, etc.), but the drama is inherent to Leila and Sahand’s circumstances. The waiting keeps us guessing, Mani’s youth keeps him in the dark to details, and the potential for things to go sideways isn’t solely a narrative device—these cases have an appeals process for a reason. We truly don’t know if their ordeal will end with them breathing easy or boarding a plane to Iran with a black screen telling us when they were killed. How can we remain optimistic if they can’t?

That’s the point. We shouldn’t. We shouldn’t sit around thinking cases like this will sort themselves out when blanket immigration bans lump innocents into xenophobic exclusions based on religion. Add the hoops they must jump through to be taken seriously as a family (a paternity test isn’t enough) and it’s a wonder refugees escape trouble at all. When marriage becomes their one chance at leaving Turkey together, it too is shrouded in suspicion. The country demands divorce certificates and Sahand can only receive his from the consulate he’s too afraid to step foot in for fear of deportation. He and Leila aren’t perfect, but neither is the system used to judge them. If it’s willing to separate their household and implicitly make Mani an orphan, something is wrong.

Rather than guess how to fix it, Mulvad is satisfied to show it instead. This is the procedure, there’s where things go wrong, and here’s the fallout. Look no further than young Mani being told in exile that Sahand was his real father to recognize the latter’s extent. It breaks him. Their lives might have been derailed right then if Mani wasn’t able to gradually understand there’s more happening here than a man he barely knows forcing him to leave his toys, home, and friends behind. These are the emotionally potent details the news ignores to preserve a broken status quo. We’re so quick to generalize and pigeonhole people into ready-made categories for mass consumption and vilification that a personal account of their struggle like this proves invaluable.

Love Child premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.