It’s 1994 and young Dudu and Duke have little in the way of inspiring role models to build lives for themselves in Mdantsane, South Africa. Apartheid is over and Nelson Mandela is president, but they’re taking notes from a father (Zolosa Xaluva’s Art Nyakama) raving about how “real men” take care of their family despite cheating on his wife with teenagers and barely knowing what his sons are doing or where they are at any moment. What he means by “protection” is the willingness to steal, cheat, and kill—to prove himself better than the next man trying to follow the law or daring to interfere with what he has ownership over. When escape is only possible through the boxing ring, jail, or death, possessions become identity.

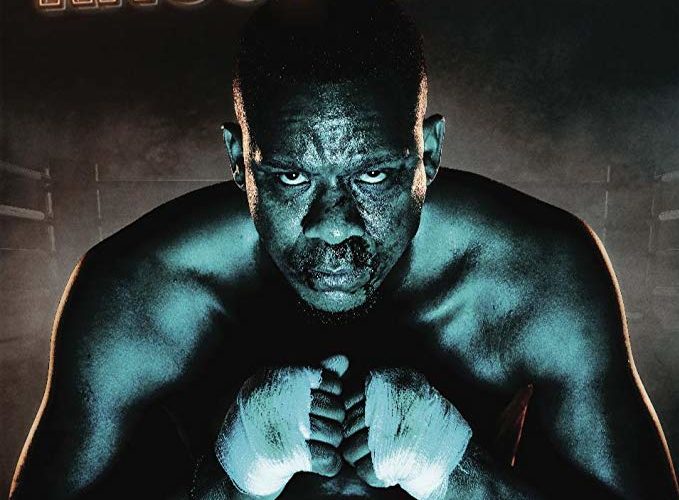

Nobody should then be surprised about where these boys find themselves in 2019 as two halves of the same chip off the old block. Dudu (Bongile Mantsai) is an aging out boxer who whores around with young girls while his mother (Faniswa Yisa’s Mother Hen) watches the ever-increasing stable of children he fathers. Duke (Thembikile Komani) is a career-criminal getting out of prison yet again to continue his fast lifestyle of opportunism and lack of regret. The young blood coming up in the ring (Sivuyile Ngesi’s Goatee) and on the streets (Athenkosi Mfamela’s Bloodshot) respect them now for who they were, but it’s ever more fleeting as time starts rendering them obsolete. One wrong step with the wrong person and the pine box their father warned about waits.

As Jahmil X.T. Qubeka says, this depiction of life where he grew up is about “understanding the wolves.” Knuckle City doesn’t seek to forgive these men and their deplorable actions, but instead contextualize where that ingrained misogyny, toxicity, and violence comes from. This is an eye for an eye environment one must steel him/herself to early in order to survive. Dudu’s eldest daughter Nosisi (Awethu Hleli) epitomizes this truth. She’s taken the role of mother to younger half-brothers and sisters, caretaker to grandma, and student to a world where sex is the sole source of pleasure removed from pain. So if anyone has the power to remind Dudu and Duke of their failings when they decide to “protect” as “real men” rather than as fathers, it’s her.

While Duke’s unbridled enthusiasm is fun to watch, we know he’ll ultimately be the cause of Dudu needing to rise to an occasion beyond his means. The elder brother isn’t expunged of his own failings simply because he’s more sensible and pragmatic, but he is trying to be better. He treats Nosisi like an adult who can make her own choices. He’s trying to rein in Duke so he doesn’t lose him for another three years because of a stupid stunt at the expense of an entitled white man who drove into the wrong neighborhood. And the “Night-Rider” himself might be settling down with an age-appropriate woman (Angela Sithole’s Minky) for once. If Dudu can get onto Goatee’s ticket, one more legitimate win might just restart his career.

Doing this means paying his promoter (Owen Sejake’s Bra Links) a bribe, incentivizing boxing legend and gangster Bra Pat (Patrick Ndlovu) with higher stakes than money, and catching the perpetually-nonplussed eye of fight benefactor Ma Bokwana (Nomhle Nkonyeni). Accomplishing all this means risking tragedy, unwittingly putting his family in the crosshairs of murderers, and ensuring his own life is forfeit against someone much younger and stronger than he in the ring. And all the while Dudu recalls the nightmarish past ruled by a domineering father to acknowledge where he himself has gone wrong following in those footsteps. Will any of these men ever really change? Probably not. But they can be better right now. They can reclaim what Art lost even if they might lose it later too.

That fallibility is key to what Qubeka delivers because it ensures we never know how dark he’ll go. The lengths traveled to achieve Dudu’s opportunity are far enough, yet Duke continues taking more until both must rely on gangsters upholding their word. Luck therefore becomes crucial too since Mdantsane never hands you anything. Whether you take it or earn it, someone will be gunning to do the same. How can they not when women like Mother Hen purposefully rile up their boys to draw blood? How can they not when men exploit their talents and refuse to hide it if it means squeezing a few more bucks from their pockets? Family might be all anyone can rely upon, but it’s more often to receive a bullet than a hug.

Toxic masculinity plays a huge role in Knuckle City because it must. While that doesn’t excuse the script letting it be the impetus for many good fortunes, Qubeka injects enough sensitivity and introspection to ensure he’s merely keeping reality intact—not condoning it. Mantsai helps create this complexity by allowing Dudu to be cognizant of his shortcomings even when they rule his actions. Where Duke truly is numb as a result of everything he’s seen and done, Dudu understands the difference between right and wrong regardless of whether he remains of the side good or not. The film is thus less about these boys beating or outsmarting an opponent than it is surviving against extremely long odds. Rather than accrue power or fortune, success is taking another breath.

Knuckle City screened at the Toronto International Film Festival.