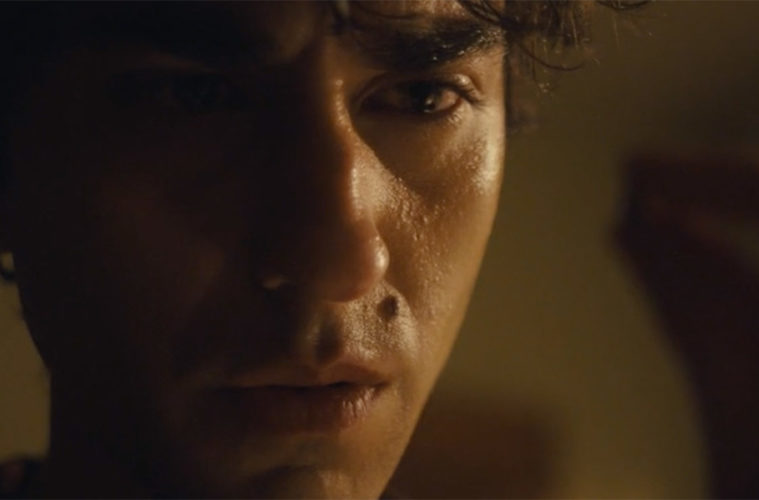

An addict is an addict whether they’ve become one via doctor’s orders or not. Sometimes the “not” part is even a direct result of those orders. When you’re working with volatile drugs like OxyContin, the line separating too much and not enough is razor-thin with the inclination being to err on the side of numb. We’re talking pain management after all and the more we take, the more tolerance we build to make the cycle worse. And for someone with Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, it can be excruciating enough to prevent your caregiver from saying, “No.” What’s Henry (Alex Wolff) to do when his mother (Neve Campbell) screams for another? As someone pushing off college to provide her comfort, how much of her suffering can he endure before agreeing one more can’t hurt?

This is the slippery slope that begins Joey Klein’s Castle in the Ground–one that’s paralleled by the plight of his new neighbor Ana (Imogen Poots). She’s struggling to get back on her feet after spiraling out of control to the point where methadone no longer works. So she starts chasing the high to get back to zero, schemes with friends (Tom Cullen’s Jimmy and Kiowa Gordon’s Stevie) to rip off her dealer (Keir Gilchrist’s Polo Boy), and ultimately drags everyone down into a dangerous cat and mouse game with people willing to kill them to get back what’s theirs. And since Klein started breaking down during his introduction at the mention of Sudbury, Ontario (where the film takes place circa 2012), that type of bad men has obviously killed a lot.

Where this instance brings the threat of point and shoot murder, the kind of genocide brought about by the opioid crisis is a much more insidious version. Maybe it’s people like Ana who escalate their drug use and subsequently get hooked on the next more volatile kind. Or maybe it’s those like Henry who find themselves in need of answers that will not arrive. Drawn as a veritable straight-edge nerd at the beginning, he stays home to watch mom while his about-to-leave-for-college girlfriend (Star Slade) goes to a party alone. He prays for his lone parent to get better, leans on positivity to protect himself from the truth, and ends up ravaged by pain anyway. Numb that sorrow once and you might never stop.

How these two (and to a lesser extent Jimmy, Stevie, and a just sympathetic enough Polo Boy despite his role in the epidemic) react to their present is where the film excels because they’re allowed to expound upon their characters’ psychological wounds. The ways in which Ana uses Henry and vice versa possess a desperation that trumps any superficial manipulations to devastating effect. We want to hope they’ll claw their way out of the hole they’re digging, but know it won’t be easy. That things get as bad as they do augments this truth via a shortcut, but it’s a believable one. I like how the imminent danger forces them into corners they don’t quite have the clear-headed judgment to escape even if it steals the wheel.

What I mean by that is the devolution of atmosphere from darkly authentic drama to straight suspense thriller. I don’t want to say it happens on a dime, but moving from the love between Henry and his mother to the race against the mortality clock of the second half is a noticeable change. Even the editing style with abrupt cuts to black at key moments shifts from melancholic inevitability to cliffhanger anticipation. It’s a testament to how good Wolff and Campbell are that we’re able to stick with the former once the plot takes control of him. That alongside a gradual peeling back of Ana’s defenses to render her as important to Henry and his Mom makes us care about their fates–familiar journey there or not.

How they stick together despite mounting tensions and increased stakes has as much to do with their skewed survival sense courtesy of a good “pop” as it does their depressive states of having nothing else to lose. Conjure a raw memory and the need for escape grows. Protect your friends enough and you eventually get caught up in their peril. Things get heavy pretty quick once the drugs take hold and not everyone will get out alive. While Klein lets that genre conceit cut some chaff for him, however, he doesn’t lose the overarching perspective that those who do narrowly get back home aren’t out of the woods. Whether they’re facing a bullet or pill, the game remains Russian Roulette. No adrenaline streak is worth the inevitable oblivion.

Castle in the Ground premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.