The big story surrounding Grayson Moore and Aidan Shipley’s feature debut Cardinals playing the Toronto International Film Festival stems from the fact that both men graduated from the city’s own Ryerson University. As a longtime festival venue/partner, this premiere will inevitably be treated as a homecoming. But don’t let that fool you into screaming “favoritism!” while dismissing it as a “homer” pick: it’s the real deal. Stripping away the college they graduated from, the knowledge that both are TIFF alumni after screening their short Boxing, and their Canadian nationalities still leaves you with a singular work of devastating emotional psychology and infectiously biting wit. So remove the local fanfare and judge it on its own merits because it earns that right and deserves any accolade bestowed upon it.

Written by Moore, the story centers on Valerie Walker’s (Sheila McCarthy) release from prison after serving a decade for vehicular manslaughter while intoxicated. He and Shipley don’t start things with the buzz of the gate and flood of light as she exits the premises, though. They decide instead to supply us a prologue depicting what happened to put her there. More a tonal collage of condensed snapshots than concrete series of events, we’re meant to hold onto its imagery and mood until context can be made visible in the aftermath. We meet Valerie at the construction plant where she works, spy upon her two young daughters drawing in the break room, and suddenly become transported to the scene of the crime. It’s disorienting, intentionally cryptic, and absolutely unforgettable.

Without denoting any passage of time, the title flashes before whisking us away to Eleanor (Katie Boland) and Zoe (Grace Glowicki) driving. It’s a minimalistic transition devoid of words (even Valerie’s conversations at the plant become inaudible with changing vantage points to ensure we know what’s said isn’t important), and yet brimming with as yet unseen implications. Whether you realize these two are Valerie’s daughters all grown up before they hug her in the prison lot is inconsequential, but the simple fact you can is a testament to Moore and Shipley’s handling of the medium as a visual art form. Dialogue eventually enters to introduce the presence of a secret and every new scene forces us to recall evidence we so blindly (and purposefully) misinterpreted at face value.

While the premise swims in heavy drama on its own, the tension inexplicably finds a means to grow even thicker once the son of Valerie’s victim (Noah Reid’s Mark Loekner) rings the doorbell. He still resides across the street, waiting these ten years to confront her and understand what happened that fateful day. It’s an awkward scenario all around as Valerie and the girls’ attempts to laugh again are cut short by the presence of the one person who had it worse then them. The conversation leads to odd questions with the whole interaction becoming more accusation-based fact-finding mission than plea for contrition or forgiveness. There’s obviously something else going on here and the longer certain parties are left in the dark, the more precarious everyone’s lives become.

Despite this palpable weight exposing a dark horror more atrocious than the known tragedy connecting these families, Moore and Shipley prove their skill with a welcome strain of humor that never feels incongruous to their goals since the characters’ ability to make us laugh is what confirms their authenticity. Each time the suspense builds due to a fresh encounter of ulterior motives between Valerie and Mark, a subtle barb of sarcasm cuts through or a deftly placed line of dialogue pushes us far enough past our threshold for anxiety to emit a gasped chuckle while those onscreen tense up more. Add a blunderingly passive parole officer (Peter Spence’s Jonah) to the equation — someone who brings leftovers to a serious meeting about a potential violation — and comedy is unavoidable.

It’s a necessity that keep things from going too dark too soon, each glimpse of humanity and discomfort a key distraction from what remains unsaid. McCarthy plays Valerie with the utmost severity to keep up her poker face and yet I think I laughed at her dry retorts more than anyone else. It helps that she delivers them with a knowing twinkle in her eye — a mixture of frustration and determination — opposite either the obnoxiously nice Jonah (Spence is a scene-stealer) or the equally guarded and shrewd Mark (Reid is forever on the cusp of falling to pieces or blowing up in rage). Her Valerie becomes a sort of bomb diffuser, always saying and doing the right things in order for everyone else — including Mark — to remain safe.

But therein lies the problem of her actions. This maternal drive to protect is what drove them towards their current predicament because her decisions never took into account the devastatingly volatile chain reaction that would eventually ensue. Valerie stole her daughter’s voice, left both Eleanor and Zoe without a mother, and rocked Mark’s entire existence in an instant. And unfortunately for everyone involved, time does not heal all wounds despite how the saying goes. It conversely has the effect of letting those wounds fester until knowing the truth becomes more important than quelling the pain. The hope was that life would move on and tragedy would be forgotten, but the opposite holds true instead. To end the charade, however, is to destroy what little peace had been retained.

Was it though? No one seems like they’ve put the past behind them. Valerie’s crime looms large over and has every day she was gone. The difference now is that she cannot hide in isolation and those who endured her silence will make sure she can’t. This is done through silent expression (Boland is ravaged by fear, but ready for a much-needed catharsis), unwitting ignorance (Glowicki’s aloofness is a product of not knowing what everyone else does), or aggressive manipulations (Reid’s Mark has planned his scheme to acquire the answers he covets with psychological precision). And all the while Valerie stands strong, confident that her silence will be their salvation. This flawed certainty leads them towards a harrowing, violent climax full of the consequences time could only postpone.

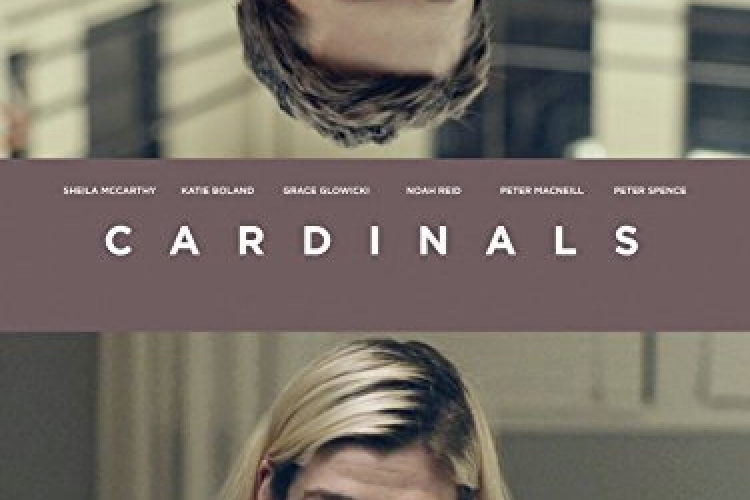

Cardinals premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.