As the end credits rolled during TIFF’s first press and industry screening of Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave, a peculiar thing occurred: very few people moved. Some quickly sprinted down the stairs, hurrying for their next screening, but many, like yours truly, just sat and stared, feeling emotionally overwhelmed by the experience. The film is that kind of success, a stunningly realized achievement that will clearly rank among the finest — if not the finest — films of 2013. McQueen, the British helmer behind Hunger and Shame, has brought America’s most shameful period to the screen with a fury and authenticity the likes of which audiences have never seen.

Perhaps a story of slavery set along these particular lines was necessary to truly connect with modern viewers, for the protagonist of this true tale, Solomon Northup, was a free man sold into slavery in 1841. (The film itself based on Northup’s eponymous account.) Solomon, played by the great Chiwetel Ejiofor, was a musician in Saratoga, New York, a respected husband and father of two. When offered the lucrative opportunity to perform with a traveling circus in Washington, D.C., he cannot help but accept. But in a stunning jump cut, we shift from a wine-fueled dinner to Solomon in nightmarish shackles, cruelly betrayed by the gentlemen who recruited him. Despite the almost 150-year time differential, the situation of a free man made enslaved is identifiable; there is a moment when Ejiofor looks directly into McQueen’s camera, and it hammers home the feeling that Solomon is one of us, and we are Solomon.

And whether one already knows how Northup’s story ended or not, we are an eyewitness to his brutal journey. One of Solomon’s early encounters after losing his freedom is with slimy trader (Paul Giamatti), with whom Solomon is rather lucky to have been sold to William Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch), a plantation owner who, about as likable as an onscreen slave owner can be, treats him with respect, even something resembling kindness. But, after an altercation with a monster in Ford’s employ (the ever-weasel-y Paul Dano), Solomon is sent to the cruel, complex, diabolical Edwin Epps. In what is perhaps the actor’s most effective performance yet, he is played by McQueen’s Hunger and Shame star, Michael Fassbender.

The majority of the film takes place on Epps’s horrific plantation. Here, we meet Epps’s equally vile wife (Sarah Paulson gives a performance unlike any she’s delivered thus far), the sweet-natured Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o), and, eventually, a Canadian carpenter played with confident efficiency by 12 Years’ producer, Brad Pitt. All are memorable, especially Fassbender’s Epps and Nyong’o’s Patsey, but there is no one who commands the screen like Ejiofor. Not every actor could make a shouted line like “I will not fall into despair” work, but nothing which comes out of his mouth sounds rote or unbelievable; the man is in almost every scene, and he nails all featuring his presence.

The film is, then, a tremendous achievement for its actors and director, but also for screenwriter John Ridley, composer Hans Zimmer, cinematographer Sean Bobbitt, and, frankly, virtually everyone else involved. It’s rare to say a movie has no false notes, but such is the case with 12 Years a Slave, a film that, days later, may still leave viewers shaking. When was the last time you experienced a movie that truly lingered in the memory? McQueen has crafted such an epic, and, in doing so, has made a 21st-century masterpiece. This is likely to be the most moving cinematic experience of the year, and if there is any justice, McQueen’s film will be required viewing in American classrooms — itself something of an ironic statement, given that McQueen is British. You want to see, hear, and feel slavery? Here is the system, in all its awful components.

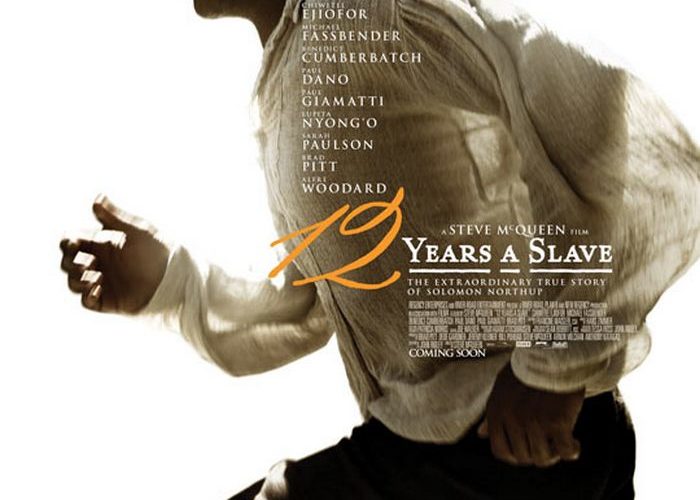

12 Years a Slave premiered at TIFF and opens on October 18. Click below for our complete coverage.