Lemon opens with a title card disclaimer: “This film was photographed and recorded in its entirety in Los Angeles, California.” It’s clear why the setting is important. This isn’t Hollywood, home to celebrities and various success stories. This is L.A., and the amateurishness and desperation of locals looking to make it big is in the air. The film plays to the setting quite a bit. The city’s cultural diversity is explored as director-writer Janicza Bravo and writer-star Brett Gelman inject aspects of their own heritage (and possibly relationship? — the two are married in real life) into the film. Then there’s the heat, which turns the film’s aesthetic as deceivingly bright as its title fruit, and a constant over-reliance on cars that serves as a sort of inside joke for the inhabitants of the city, who become neutered without a means of transportation.

The first shot focuses on a television screen, as an African Woman (Inger Tudor) emotionally describes the war-torn conditions of her country, before the camera slowly pans to middle age Isaac (Gelman), who teaches an acting class and mistreats his blind girlfriend Ramona (Judy Greer), also present. Her leaving him is the most significant in a series of otherwise minor tribulations, all of which he responds to in the most inept, frustrating ways. The film hardly takes its characters seriously. It does everything in its power to keep the pathetic Isaac from being sympathetic — he is misogynistic, racist, socially awkward — and in doing so, shoots itself in the foot. After all, unsympathetic characters are, by nature, hard to be interested in. Most of the humor stems from the humiliation of its protagonist — the binding thereof — and it is all quite funny, in a demented, cringy way that makes it difficult to sit through. Here, Bravo’s experience directing theater shows, as long extended shots with exquisite framing wring out the painful anxiety in each scene.

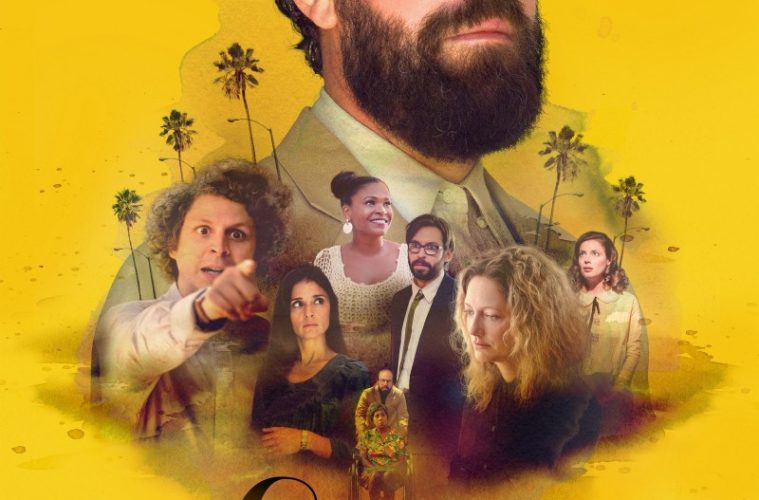

A miserabilist comedy in the vein of something like Entertainment or The Comedy, it’s satire of the media industry in the first act feels minimally purposeful only in how it mocks the performance process. It’s a strange beast, at once somewhat reductive towards the artistry involved in acting, but simultaneously a product of that very same struggle. These moments, set in Isaac’s acting school, are stolen by Michael Cera, whose laughably radical methods are some of the film’s most conventionally entertaining to watch. Brief moments seem to hint at some larger form of commentary. Isaac’s brother, Adam (Martin Starr) at one point criticizes the commercial industry’s employment of false figureheads after Isaac, free of STDs, stars in a PSA about STDs, putting Isaac down while bluntly making a charged point.

The cultural diversity at play here is one of the more interesting facets of the film. The second act follows Isaac at a family reunion for Passover, where Gelman’s jewishness becomes a factor. The third act follows Isaac as he courts African-American Cleo (Nia Long), who introduces him to her family friends at a barbecue at which he struggles to fit in. Both of these scenes end with bombast — two largely unpredictable, hilarious, seemingly significant events (if the music would have you believe), but they don’t amount to much apart from reiterating that Isaac is sort of an odd fellow.

Lemon opens on Friday, August 18.