Jimmy’s Hall, rumored to be Ken Loach’s final film, condenses the various political ideologies and conflicts of post-civil war Ireland into a manageable historic overview for its viewers. The film opens with Jimmy Gralton’s return from the United States to his native Ireland. This sequence, which should establish the ethereal beauty of the landscape and the gravitas of the film’s titular character, is dominated by title cards explaining the historical context of Gralton’s life, British aggression, and ratified treaties. Loach’s approach here is jarring. This is the filmmaker who dropped us into the complexities of the Irish War of Independence and Civil War, two events directly informing the content of Jimmy’s Hall, in his Palme d’Or-winning feature The Wind that Shakes the Barley, without such an academic approach.

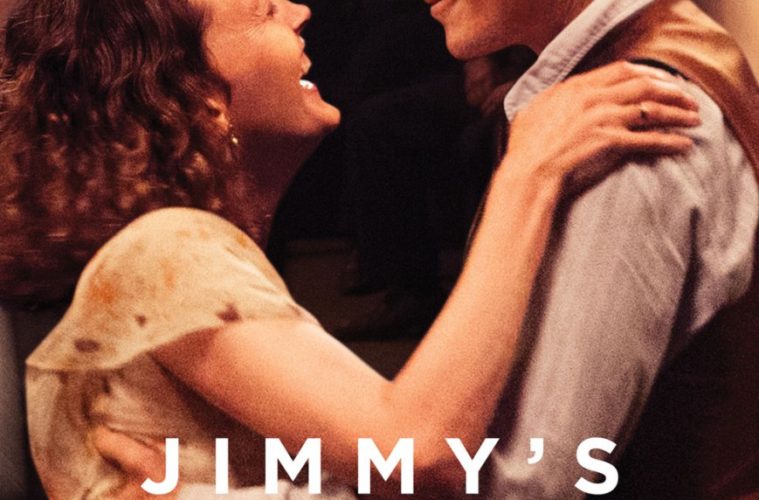

Jimmy Gralton (Barry Ward), forced to exile to the USA for his communist activities, is determined to stay out of the political arena upon returning home. His widowed mother, his old friends, and an previous love interest Oonagh (Simone Kirby) have settled into domestic lives. The dilapidated village hall, which once housed community dances, classes in arts and literature, and functioned as the hub for those dissatisfied with the course of its oppressive government leaders and religious institutions, is the lone remnant of Jimmy’s political life.

Given that Loach’s film quickly becomes about the struggle to re-open and protect the hall, with those who support the effort pinned as the heroes, Jimmy’s Hall bypasses whatever complexities hinted at in that historical-heavy opening. Loach and screenwriter Paul Laverty paint the Catholic Church, spearheaded by Father Sheridan (Jim Norton), as the clear villains. It’s the Church who serves violent parishioners, stern fathers who beat their daughters, and who direct their wrathful proselytizing at Jimmy for his political outlook and life choices. For a film that begins with complex characters and historical situations evading a clear moral stance, it feels like a regression to see characters rendered in such archetypal fashion as the film progresses.

Also proving troublesome is the inconsistency of the performances. Ward is committed to a portrayal of an oppressed and yearning Gralton. It’s hard to pinpoint where his character is emotionally, however, because the film crams dramatic beats into awkwardly constructed flashbacks. Ward as Gralton, in a short span of time, has to convey the optimism at the construction of the hall, fear the impending interference from the church, and serve as a leader to a mob. Also, Ward is often pinned against in scenes against a bombastic performance from Norton as Father Sheridan. Both actors are reduced to the talking points of their respected characters, only Norton as the malicious priest does it louder and with unwavering intensity. He also offers the most dynamic acting in the film.

Still, Loach is a talented enough filmmaker to completely squander material so seemingly in line with his aesthetic and thematic sensibilities. Over a discussion of poetry at the hall, the question gets asked, “Does all that longing break your heart or fill you with hope?” The film’s best moment poses this question visually – as Father Sheridan and his squad of priests take down the names of those traveling to the dancehall alongside the road. Here, Loach’s reminds us that oppression does not have to function on a colossal scale for it to impact the lives of the people. I only wish more of Jimmy’s Hall was rendered in this sort of evocative minutia than the bland sweeping overview it strives for.

Jimmy’s Hall is now in limited release.