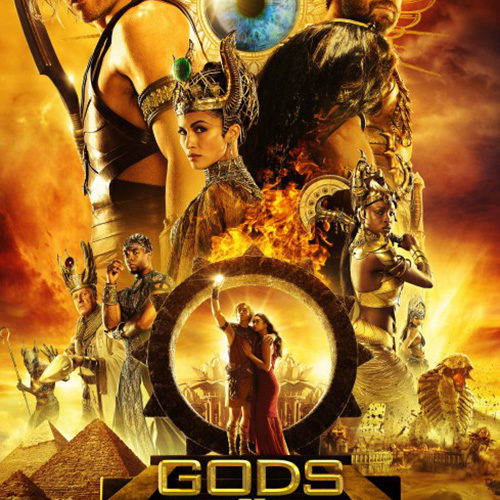

It’s tempting to want to give too much credit to Alex Proyas’ Gods of Egypt for sheer invention. Not since last year’s polarizing belly flop, Jupiter Ascending, has a blockbuster been so filled to the brim with intricate, nonsensical, transcendently stupid world building. Within the first twenty minutes, an amber-encrusted Egypt obsessed with pageantry and grand gestures becomes a fiery hellscape ruled by winged mechs with designs based on dense Egyptian mythology shooting laser beams at each other.

From there, the mythology keeps building an ornate, jeweled ladder to nowhere, throwing in every manner of insane set decoration, from immortal leviathans made of smoke to chariots led by gigantic scarabs to floating portals to nether realms. But while the film becomes a constant test to outdo itself, the raw ambition isn’t nearly enough to make up for the content of the actual film: an ungainly, ugly, nearly interminable monstrosity.

As the film begins, Egypt has seen a century of peace thanks to the benevolent ruling of the God Osiris (Bryan Brown). But his time has come to an end, and he’s preparing to relinquish the throne to his son, Horus (Nikolaj Coster-Waldau), a cocky playboy with an inherently good heart. That doesn’t sit well with Osiris’ exiled brother, Set (Gerard Butler), who has returned for the coronation. Enraged at his station in life, he kills his brother, and leaves Horus blinded, before taking the throne and immersing Egypt in a cycle of war and enslaving the people of Egypt to erect grandiose monuments in his honor.

Banished to an unknown location, Horus waits in darkness for his followers to return his eyes, the source of his strength. His followers don’t come, but a street urchin mortal named Bek (Brenton Thwaites) miraculously manages to retrieve one of his eyes. Spurred by his idealistic girlfriend Zaya (Courtney Eaton), Bek believes that freeing Horus is the only way to return Egypt to its former greatness.

Using maps that are only available through Zaya’s job as the assistant to the king’s lead architect, Bek locates the vault holding one of Horus’ eyes and navigates a series of lethal booby traps befitting an Indiana Jones installment before breaking free Zaya and heading off to find the blind hero. That’s a convoluted string of events in itself, complicated further by the death of Zaya, who’s killed by a few perfectly aimed arrow, becoming the axis of the entire story.

As Bek begs Horus to resurrect Zaya, she’s sent to the eternal DMV known as the line to the underworld. But luckily, Horus has a solution. If he can reclaim the throne from his tyrannical uncle then he will be granted the power to resurrect anyone he wishes. Soon, they’re thick as thieves, wisecracking and adventuring across bizarre lands and fighting magical beasts. Unfortunately, what follows is less an entertaining popcorn adventure than a green screen extravaganza spammed with endless CGI that’s indistinguishable from current generation video game consoles for huge swathes of time.

Even their destinations could serve as templates for element-themed video game worlds – the ancient ruins level, the fire level, the forest level, etc. In this age of blockbusters, this level of artificiality isn’t uncommon, but there needs to be some sense of engagement with what’s happening on the screen. The stakes are nonexistent as Horus hacks and slashes beastly grunts and wrestles with anthropomorphic sphinxes as the camera spins around with the same floaty axis that comes with playing a modern button-masher.

When Proyas isn’t dealing with eye sores, it’s clear he can frame a scene. One of the earliest sequences in the film, set in a bathhouse, is nearly elegant in its framing, placing Horus within the frame with economy before gracefully zooming out to demonstrate the exotic architecture. At its best, the visual milieu is fondly reminiscent of Tarsem Singh’s Immortals, his immensely flawed but visually stunning ode to mythology. But too often, the screen is gummed up with nothing more than stuff to communicate scale, falling into the same pratfalls of latter-day Peter Jackson.

The performances may be the one dimly-bright spot, but that’s not to say they’re good, rather actively entertaining. There’s long been a choir singing about Butler’s need for a new agent, so there’s no need to repeat those sentiments, but he really is pretty great as the brutish Set. There’s nary a line that couldn’t double as an entendre, and he’s practically purring them out. Coster-Waldau knows his way around a one-liner, maximizing his ability to bring a pretty boy arrogance to his line readings, but he’s still never been able to surpass his turns in Game of Thrones or Headhunters. Meanwhile, Thwaites has a face for YA adaptations with his malty eyes and gleaming smile, but still has yet to prove himself as anything more than a distraction. Eaton, his love interest, is given even less to do in a purely reactionary role.

The supporting cast does have some unexpected gems. Chadwick Boseman is still a relatively unknown quantity, despite a lead turn in 42, but as Thoth, a smug know-it-all, but he manages to bring a real charisma to a character that could have easily been incredibly irritating. Geoffrey Rush is even bolder as the God of all creation, Ra. Clad in robes that resemble the Pope and enthroned in fire, his performance is all explosive outbursts and muttered annoyance, but he’s hypnotizing all the same.

There’s more to say about the utter insanity of the climax, in which the world threatens to literally engulf itself, but Gods of Egypt sounds ten times more fun on paper than it does in practice. The audacity of its failure is at least enough to ensure a shelf life in podcasts about bad movies. In reality, it’s an endless slog that loses its WTF factor long before the credits have rolled.

Gods of Egypt is now in wide release.