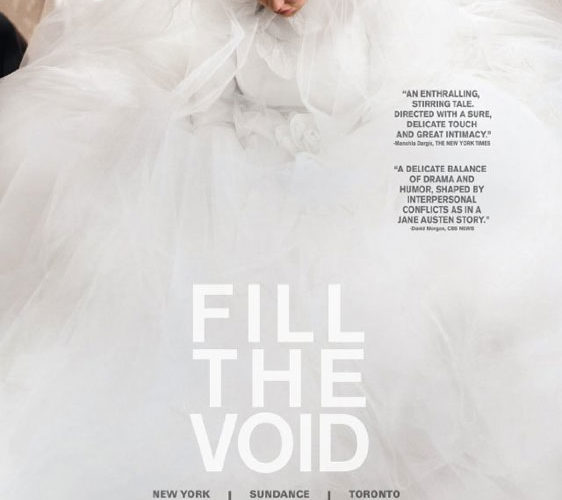

Rama Burshtein’s Fill the Void is an intricate and intimate portrait of a world insulated against the modern and secular; it could well be a previous century for all its values and antiquated traditions, but it belongs to the haredim, an ultra-Orthodox Jewish sect in Tel Aviv. Burshtein, a resident of Tel Aviv and a female member of this community (by choice, not birth), brings an observer’s eye and an insider’s understanding to this secretive enclave.

The story itself is a model of simplicity, cutting directly to the tension and struggles characterized by extreme orthodoxy, even in a segment slightly more relaxed like the one portrayed here. Eighteen-year old Shira (Hadras Yaron) has a dilemma that will decide the fate of her forthcoming years; who will she marry? There’s a courtship and subsequent engagement to a red-bearded young Hasid, but these plans are halted when her older sister Esther (Renana Raz) dies during child-birth leaving her newborn son and widower Yochay (Yiftach Klein) in the wake.

Although taken back by the loss, Shira’s mother suggests that perhaps her daughter and Yochay may wed, if for no other reason than to prevent her grandchild from leaving Israel for Belgium. Of course, that’s not the only reason that emerges for the parties involved. Although Shira warms to the often brooding and unreadable Yochay, she’s trapped within a moral and emotional stalemate with her own conscience, fearing a betrayal of Esther’s memory in her actions.

Yaron delivers a sensitive and insightful performance, engaging the audience’s sympathies and curiosity over Shira and how she truly views her place within both the microcosm of her own family and the larger one of this community. Shira as a character is modest in her speech and careful and discreet when revealing her thoughts, but the actress uses body language and facial expressions to suggest conflicts and passions underneath that inform her actions and choices. Klein as Yochay matches her with a turn that is compelling and focused, but often inscrutable to exact emotion. His reservations look often like moral superiority but the chinks left in his armor by his wife’s passing tell other stories.

Burshtein has emotional ties involved and paints the treatment of women here with a narrow brush specific to this individual community—their opinions are listened to and valued, they have some latitude when it comes to decisions like the one before Shira, and they occupy a focal point in the society—but this perspective is important to absorbing who her characters are, and how this life has shaped and will shape them. She takes the time to portray the routines and observances of the culture and how they tie into implied devotion, while often illuminating specifically the female perspective, even when it appears limited and fragile to secular eyes. Burshtein is a natural storyteller and an effective and gifted filmmaker, who offers up a culture not cloistered and drab, but full of feeling and emotional urgency, held-in-check and sometimes inflamed by the laws and customs of its faith.

The camera angles and shot compositions open up two worlds; one depicting the fastidiously coiffed human architecture of the haredim—side-curls and wide, dark hats contrasted against less usual sights like a young woman’s accordion—and the other reflecting the rich, furtive landscape of Shira’s own head-space. The first is concrete and evocatively etched, vibrating with energy even when it initially appears insular and cramped. The second is mostly implied through scene lighting and placement of Yaron in her environment. The final sequence of the film leave us with this other realm exposed to a certain degree, as Shira offers up her own measured feelings through body language and poise alone.

Burshtein’s outstanding work is not a religious screed interested in proselytizing. Instead, she’s relating a very specific and palpable female view from within, embodying the way all members have the weight of family, faith and tradition upon their heads as they make life decisions many defer to the heart on. She has done this with a mostly unbiased introspection and with a quiet poetry that may, in fact, lead to great things in the future if she’s willing to follow that curious fire burning behind Fill the Void.

Fill the Void is now playing in limited release.