About halfway through both Jean Renoir’s and Luis Buñuel’s interpretations of Octave Mirbeau’s 1900 class satire, A Diary of A Chambermaid, there’s a scene where Joseph – the sociopathic valet – proclaims his obsession with Célestine. “We may be different on the surface, but we’re the same underneath,” Joseph slithers out as he grabs her.

For Buñuel, it’s the emergence of a pattern of wanton perversion, a moment that showcases the director’s personal fondness for abrasion, while also blurring his intentions with Célestine. For Renoir, it’s the Hollywood introduction of a sinister villain, a possessive sadist who covets Celestine for her perceived impurity. But in Benoît Jacquot’s psychologically sublimated adaptation, the scene never comes.

Joseph (Vincent Lindon) isn’t the hunter, he’s the prey, and as much as Célestine talks about being tangled in his lurid magnetism, she’s fully in control of both of their fates. Jacquot’s interpretation attempts to parse the story as psychological fencing and emotional masochism, but his direction and storytelling decisions constantly cloud the film’s purposes.

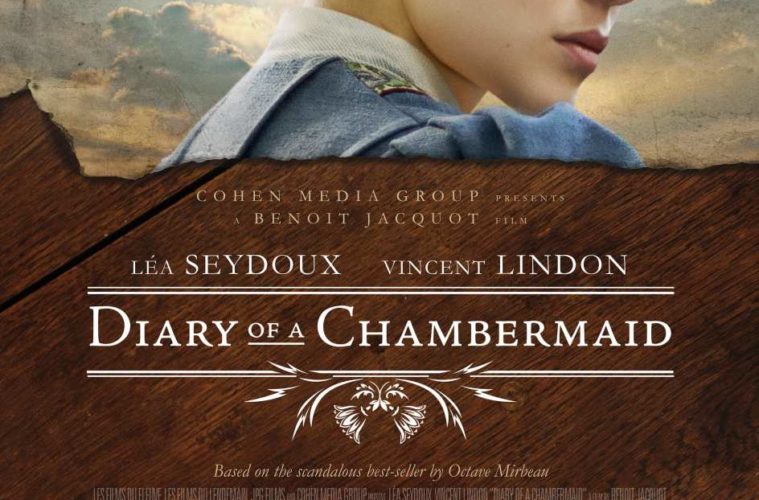

Diary of a Chambermaid follows Célestine (Léa Seydoux), a prickly servant who’s tires of her position in life, and schemes of being her own master, while under the employ of the Madame (Clotilde Mollet) and Monsieur Lanlaire (Hervé Pierre), a bourgeois couple with no illusions about their unstable marriage.

Madame Lanlaire treats Célestine as if they’ve had an eternal grudge, wearing her down with pointless tasks like forcing her to sprint between floors for every individual piece of a sewing kit, or berating her for not working hard enough when she finds out a family member passed away. Célestine isn’t the average servant. Compared to her more docile counterparts, she has no problem stepping into a dominating position, regularly taunting her superiors with quick-witted retorts and rebellious behavior like stealing their food. All the while, she’s dodging romantic invitations from the lecherous Monsieur (Pierre), a flower-eating Captain (Patrick d’Assumcao), and Joseph, who seethes with lust.

The story is told in a nestled flashback structure that interrupts Célestine’s time with the Lanlaires for her experiences with previous mistresses, such as a snooty one whose late night activity is paraded in front of an entire room of taunting onlookers, and a sick teen, Georges (Vincent Lacoste), who Célestine falls in love with. Diary of A Chambermaid carries a weighty art house ponderousness, but it rarely feels focused or connected with the film’s largest aims. These sequences veer the closest to melodrama with one scene that’s straight out of Downton Abbey with Seydoux screaming, “Look how afraid I am,” as she climaxes.

Backed by sinewy piano lines, a disaffected compositional style and clinically elegant production design, Diary of a Chambermaid aspires for the probing psychological portraits of latter-day Francois Ozon, but for a film that’s ostensibly about passion, it feels particularly stunted. The camerawork feels modulated for insinuating suspense, but more often, it just enhances the strained sense of repression on screen.

Seydoux plays Célestine as a masochistic ice queen, cocky and disdainful of her station, but also delighting in the attention whether it’s wanted or unwanted. In Buñuel and Renoir’s interpretations, Célestine was always the tease, a women who suggested sexual energy, but was never able to act on these impulses. Jacquot’s version has far more sexual agency, free to seduce and be seduced. But while Seydoux’s performance is intensely watchable, it’s ultimately at odds with the various subplots, which all hit unsatisfying dead ends.

Jacquot’s Diary of a Chambermaid ultimately feels beholden to art-house dictates, especially with an ending that’s less confounding than poorly articulated. Jacquot has updated Mirbeau’s milieu with a group of France’s finest actors, and a moral maturity that’s less concerned with conceptions of justice than the thrill of that moral ambiguity, but it’s all built on a foundation of false equivalencies.

Diary of a Chambermaid is now in limited release.