A movie that attempts something new or controversial is often instead deemed “risky,” but that term does not even begin to describe Closed Curtain, which also carries the risk of making a film despite being imprisoned and banned from filmmaking. Even more so than his aptly titled previous feature, Jafar Panahi’s latest work is simultaneously a cry for help and a zealous statement that, given his current living situation, filmmaking is the only thing Panahi has left.

That may sound excessive, but Closed Curtain makes more than a few references to suicide. Early on, a refugee, Melika (Maryam Moghadam) tells The Writer (co-director Kamboziya Partovi) — a fellow refugee whose house she has wandered into — “[suicide] beats living behind closed curtains like you. Suicide is your only way out.” Later, when the film begins to reflect back on itself, a recording of her that Panahi watches through his iPhone sees her tell him, “follow me” before she drowns herself, a sequence we see repeated shortly thereafter with Panahi in her place, only for the footage to be rewound as if some sort of perverse fantasy. A friend tells him that there are more things to life than work, to which he replies, “yes, but those things are foreign to me.” The art of filmmaking and the opportunities to partake in it — even during the gravest of times — is, quite literally, keeping Panahi alive.

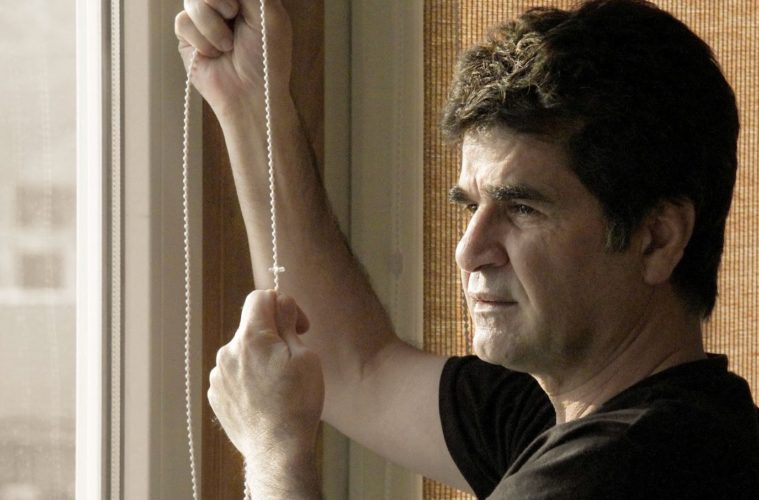

Closed Curtain begins like it could be any arthouse film. The camera stares out the window for a couple minutes before The Writer enters, takes his pet dog out of his bag — we’ll soon see that dogs are no longer legal pets — and goes about his house. Craft is immediately on display; the shot approaches eight minutes before breaking, while the interior is a three-story architectural wonder that the camera effortlessly glides through. At the same time, we can already see Panahi crying for help: The camera can stare outside, but, like the filmmaker himself, it cannot leave; the camera is constantly in shallow focus, harkening back to the iPhone aesthetic of This Is Not a Film, in turn mirroring Panahi’s inability to truly “see” from his own prison.

Closed Curtain proceeds for more than 20 minutes before another person graces the screen, the aforementioned Melika and her brother, Reza (Hadi Saeedi), interactions between the two, again, littered with meta-text. Discussions of suicide are especially heavy considering how much of a stand-in for Panahi Partovi’s character would appear to be; Melika’s question to him about why he is writing a script when it’s impossible for someone else to turn it into a film could just as well be Panahi’s own conscience speaking to him.

But then Closed Curtain begins to venture toward an altogether stranger place. The Writer tries to replicate the events that led these refugees into his house — a mystery, as he swears he shut the door — and records it on his phone. Then Melika reappears, tears down the black curtains that keep authorities from looking in, and Panahi himself walks into the frame and begins to admire the posters of his own films that decorate the walls before covering them up again. Near the conclusion, Panahi watches The Writer’s phone recording of the recreation of the events that let the refugees in, and this time we get to see the film itself being made, as if Panahi were making that film and decided to turn the camera on himself again.

That’s exactly what must have happened: The Writer and Melika were just Panahi’s characters. Suddenly, the discussion about whether Reza was Melika’s brother or husband click into place, revealing themselves as a representation of how Panahi is trying to fill in the details of his story. Melika drowns herself, but she still creeps into the film as Panahi is unable to free his mind of his uncreated characters. That Panahi becomes the main character when the curtains are pulled down and the windows break seems to represent the intrusion and fright of reality — Panahi cannot legally make this film, and one of the men who fix the window bluntly states that he’s afraid to take a picture with him due to potential legal consequences. Melika tells The Writer that “you can’t steal reality,” explaining why the burglar’s did not take anything, but what they can steal is security and comfort, and the fact that the curtains are down and the windows are broken means that things aren’t as safe as they used to be.

Closed Curtain may get caught up in its personal statement, but intimacy is matched by density. The curtains are what keep Panahi safe, but it’s only when they’re torn down that he can see what the outside world brings. It takes a movie character to bring those down, meaning that it’s the very act of making Closed Curtain that allows Panahi a taste of the exteriors that his camera can fixate on but never enter. It’s also the act of making Closed Curtain that lends him visibility to the “reality” that could break in on him at any moment. That Melika and Reza, ostensibly movie characters, enter through the door that The Writer did not properly shut reinforces the metaphor that Panahi’s characters cannot be shut out; indeed, whenever The Writer thinks they have left, they are suddenly in the apartment again. One is the believer, the half of Panahi that keeps going, while the other is the skeptic, the other one telling him to give up. That they both are presented as characters tells us who wins.

With its auto-critique and self-referential aesthetics, Closed Curtain attempts to cure an inability to connect with the outside world precisely by recognizing that problem. As an examination of the shifting faces of doubt and bravery against political oppression, a meditation on filmmaking, and a chronicle that is at once universal and intimate, film, as an expression, has never felt so important.

Closed Curtain is currently screening at the Seattle International Film Festival.