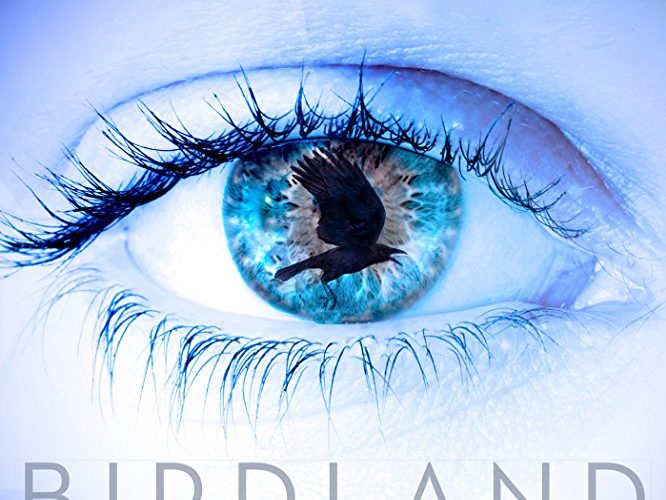

Some filmmakers keep their endings ambiguous so the art lingers with the viewer in order to interpret the piece rather than merely consume it. Writer/director Peter Lynch looks to go one step further with his noir Birdland (co-written by Lee Gowan) by rendering the whole a mystery wherein beginnings and ends are both fluid as far as linear coherency is concerned and meticulously structured to amplify the emotional machinations of his lead Sheila Hood (Kathleen Munroe). Lynch intentionally disorients so that mood overshadows action. He focuses on Sheila’s place within a story branching off in multiple directions independent of her despite her obvious visible presence within each as lurker, voyeur, lover, or friend. Is she therefore a victim of external circumstances or the one deliberately pulling every string?

Even before the title flashes across the screen we’re drowning in images strung together as though tonal poem, gleaning that Sheila is a private detective or police officer following a couple at night (David Alpay’s Tom and Melanie Scrofano’s Merle). Suddenly it comes into focus that Tom is actually Sheila’s husband, the “case” his stepping outside her own marriage. The scenery is constantly changing while the clinical lens of observation remains the same, her task objectively devoid of the jealousy and rage we’d naturally assume she’d possess. And then we watch Merle walk onto a bridge before a quick edit to a woman screaming in the train below transitions to her slomotion descent to an assuredly swift death. Did Sheila watch Merle fall? Did she supply a push?

Lynch barely provides time to ask those questions before showing brief vignettes of a dark-haired Sheila with Tom at home, the sexual exploits of Tom and a blonde-haired Merle in bed, and shots of Sheila waving into the many surveillance cameras she set-up inside her home and Tom’s work. But before we can process that we’re whisked away to Calvin (Benjamin Ayres) meeting a now blonde Sheila at station headquarters wherein he takes her badge and leads her towards interrogation under the assumption Tom murdered Merle and a man named Ray Starling (Joris Jarsky). So our minds are racing yet again. Who is Starling? When did he die in relation to Merle? Is that blonde woman in bed with Tom actually Sheila? Down the rabbit hole we go.

The hair is necessary to mark the passage of time, but even with it we remain unsure about what if anything is real. Eccentric characters are introduced in the form of Merle’s oilman father John James (Stephen McHattie), flirtatious sister Hazel (Cara Gee), and mystery cowboy Bob McIntyre (Earl Pastko). Sheila is eventually seen inserting her way into all their lives: investigating sabotage in the James’ business and helping Starling find a murderer all while keeping tabs on the woman stealing her husband away. We realize just how clichéd these cyphers are from the egomaniacal and financially wealthy opportunist to the overly sexualized femme fatale of distraction and multiple motives. Identity gets muddied as intentions sharpen. And those short snippets from the start begin to expand with clarity.

Present-day consists of the interrogation with Calvin incredulous in his attempts to coax a reaction from Sheila. Why is she ignoring evidence that implicates Tom? Why does she admit to never confronting him about the affair? And what parts of what we’re shown is surveillance footage that Calvin projects atop the police station’s walls or third-person memories of warped reality? At one point Sheila even manipulates video on her computer, forcing us to infer that her fingerprints are all over the crimes swirling and the so-called “truth” as Lynch presents it in clipped passages that we might never fully experience. He toys with us while Sheila toys with Calvin. The answers are there to give, but they’d both rather let the darkness of not knowing prevail and incite.

The result is inherently divisive. As many audience members watching with investment in the complex mystery will ultimately detach themselves upon discovering their yearning for answers is only ever met by more questions. It gets so confounding that I began to believe the same actor played both Sheila and Merle because I stopped being able to tell them apart. Is that the blonde traveling towards oblivion or the one we’re meant to accuse for sending her there? Hell, you may even think one didn’t exist at all. It doesn’t help that Sheila is introduced to some characters more than once as a product of the plot’s secretive nature and/or manifestation of her duplicitous existence. Everyone leads two or more lives and Lynch augments that confusion with his structure.

He frustrates as a means to engage, utilizing noir tropes so that we feel rather than see. Birdland‘s excess of subplots mask the truth rather than bolster its revelations, drawing us in to pretend we have a bead on who these characters are only to show how inconsequential our desire for more is to understanding what’s happening. Looking back on the whole reveals a very familiar line from A to B that Lynch has buried beneath surface noise before chopping it apart. It’s as though he’s deconstructed the genre and rebuilt it in a way where its traits become more important than the blueprint holding them. He understands that we love hard-boiled narratives because of their particular style. He’s created a film wherein that style becomes its substance.

The film becomes similar to the birds Tom’s ornithologist reassembles for his museum show (sponsored by John James of course). It’s easy to say it’s one thing because it resembles it on the surface despite reality proving much different. Birds today don’t descend from the bird-like dinosaurs of old — they share more in common with the reptilian ones. So while Lynch’s film looks like noir, it’s more post-noir than neo. The result is more a commentary on the genre than an entry into it because it’s entirely self-aware. Sheila uses its devices in spinning her yarn just like Lynch, twisting Calvin’s head much the same way ours teeters between excitement and confusion. They’re willfully obtuse so we pay attention, the endless possibilities always more thrilling than the truth.

Birdland hits limited theatrical release in Canada and VOD in the United States on January 26.