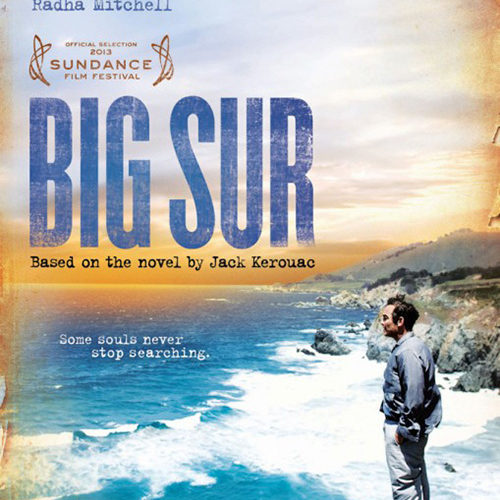

I’ve never read a novel by Jack Kerouac—the only Beat Generation tome I have leafed through is William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch—but I imagine the experience is similar to that of watching director Michael Polish’s adaption of the author’s 1962 work, Big Sur. The film is a literal stream of consciousness depiction of the legend’s own word, eight-five percent driven by voiceover narration assumedly being read directly out of the book. This is all backed by a sprawling Explosions in the Sky-lite score from The National and gorgeously composed images of the On the Road scribe’s (non)fictional band of bohemian hedonists and the California environment they inhabit. An ingenious way to bring the story to life, such an experimental visual form’s potential to captivate might leave something to be desired.

One half of twin indie darlings The Polish Brothers—who had before now worked exclusively as a team—Polish utilizes the dazzlingly constructed imagery that made Northfork such a beautifully sumptuous work to give Kerouac’s recounting of the months following his whirlwind three years of fame an almost otherworldly vibe. We enter conversations without seeing their beginning or end; struggle to hear what characters are saying before realizing Jean-Marc Barr’s oral account as Jack is describing these interactions as they’re happening; and ultimately get transported into the alcohol-haze of evening excess, morning hangover, and the stir-crazy boredom induced by what’s offered as a quiet, contemplative retreat of isolation courtesy of poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s (Anthony Edwards) west coast cabin on the sand.

The subject matter deals with personal demons battled post-On the Road, introducing Kerouac as an almost forty-year old lost soul far removed from the 26-year old hitchhiker the world believed him to be, thanks to his groundbreaking masterpiece. This Jack—less than a decade before his untimely death—is troubled by notoriety yet scared of solitude. He wants the peaceful tranquility away from New York that a summer on the beach provide, yet can’t help himself from making a large enough scene so his entire San Francisco commune of new age thinkers know he’s arrived. One phone call gets Lew Welch (Patrick Fischler) to chauffeur him around or Philip Whalen (Henry Thomas) to wax philosophical, but as his drinking increases so too does the neurotic paranoia propelling him towards nervous breakdown.

We see a disapproving glare from Ferlinghetti watching his friend self-destruct rather than heed his advice; see cold rivalry with Michael McLure (Balthazar Getty); idolatry from Lew’s young lackey Paul Smith (John Robinson); and the perfect symbiotic friendship with Neal Cassady (Josh Lucas), a man only recently excised from jail after serving time for marijuana possession. The experience had by these peace loving sexual revolutionaries wanting nothing to do with societal of moral constraints — a precursor to hippie culture, as far as its desire for the freedom of pleasure, while also a direct antecedent of hipster culture for its beatnik bohemian image — is on full display as mistresses come, go, and get passed around, all while raucous parties continue into the late night hours as wives go to sleep in empty beds.

Polish takes the irreverence of the novel and turns its vignettes into semi-surreal moments mixed with the cloudy interpretations of serious moments, all filtered through an alcoholic’s eyes as less pertinent than they really are. Passages with death looming above them like Jack and Neal’s friend Albert dying of Tuberculosis turn into playful scenes of hide-and-seek with childish smiles and pure joy fighting against the example of mortality staring back at them. And as far as love’s concerned, just when we believe Jack as he speaks of a grand four-way marriage between he, Neal, Neal’s mistress Billie (Kate Bosworth), and Neal’s wife Carolyn (Radha Mitchell)—whom he loves—his penchant for self-destruction leads him onto a selfish path of insecurity and disloyalty towards a pleasure he’ll never believe he deserves.

Big Sur resultantly turns into a visual poem of flowery words and artistically rendered visual stimuli enhancing them. Each character is stilted in their performances to push forth the idea that none are actually the true embodiments of Kerouac’s friends, but instead his shadowy memories of them while lost in a drunken stupor of epic proportions. Or maybe it’s just the carefree lifestyle they live—one allowing the notion of a day out to consist of one sleeping the whole time, while the other stares off into the distance in silent introspection. We see Kerouac fall into despair during his first trek to Ferlinghetti’s cabin alone, enjoying the company of his crazy sidekicks the second visit, and crippled by hastily made plans for marriage to his best friend’s mistress the third.

Despite so much happening on the surface for Barr’s narration to appear emotionally heavy against his character’s fragile state of being, however, Kerouac ultimately finishes exactly where it started, as though everything was merely a dream concocted within the tumultuous recesses of his sleep-deprived brain. The mostly silent vignettes are beautiful in their simplicity—watching through the Cassady’s picture window as Jack purposefully introduces Carolyn to Billie with Neal helplessly looking on is an inspired bit of perfectly blocked voyeuristic intrusion—and the actors play up the fabricated aura of Jack’s experiences nicely, but I still found myself asking, “That’s it?” I applaud Polish for adapting a free-form novel about mental deterioration with equal formal abstraction, but at some point you must wonder if you should have simply read the thing instead.

Big Sur opens in limited release on Friday, November 1st.