Something isn’t right. Jonathan (Ansel Elgort) is tired despite his routine bordering on monotony being the same for who knows how many years. He wakes at 7:00 am without an alarm, goes for a morning run, and heads to work as a draftsman at an architecture firm run by a man he respects as a genius. He returns home, films a video message to his roommate about the details of his day and any interactions with mutual acquaintances, and goes to sleep … at 3:00 pm. His television pops on as the next day begins to show someone who looks exactly like him with a much more laid-back demeanor. John (also Elgort) talks about playing basketball with friends instead of what happened at work. And he says he’s tired too.

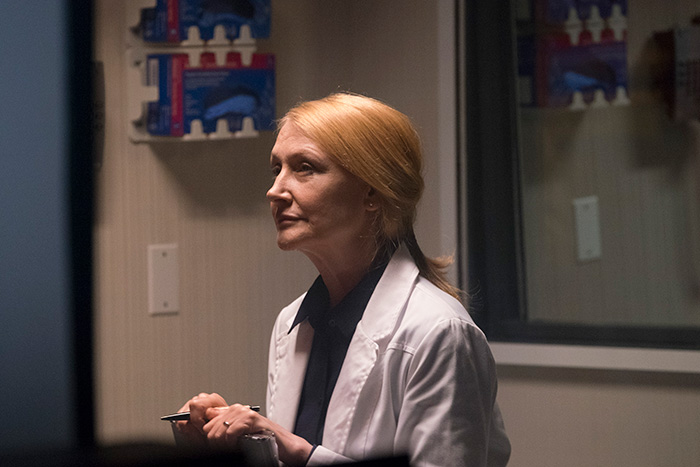

What we quickly discover is that while Jonathan and John are roommates, their apartment isn’t the only domicile shared. There’s also the body housing their individual consciousness flipping between the two on the sevens thanks to an ingenious device that Dr. Mina Nariman (Patricia Clarkson) implanted into their neck. Jonathan gets the day shift (7:00 am to 7:00 pm) while John gets the night (7:00 pm to 7:00 am). It’s an arrangement that’s worked since these brothers were teenagers and it obviously must come with rules. The biggest of those is recording a daily message to ensure their respective ducks are in a row as well as to interact considering they’ll never be able to do so in-person. Theirs is a loving relationship wherein they truly only have each other.

This is why a sudden onset of fatigue is problematic. It could be stress, age, or any number of things, but it could also be sabotage. Since Jonathan is the responsible half of their pair who’s sacrificing progression within his career due to being available fifty percent of the day, he believes John is the culprit. We agree with him too since we also only see his doppelganger via the TV screen. Because director Bill Oliver (who co-wrote with Peter Nickowitz and Gregory Davis) has made it his film Jonathan is always shown via its title character’s perspective, we know it’s not him. So Jonathan discovering a bar napkin in their laundry creates paranoia that John’s outraged response to accusations subsequently exacerbates. He needs to know what’s happening.

Long story short: it’s a woman (Suki Waterhouse’s Elena). Blatantly disregarding one rule (no girlfriends), John must break another too (lying). A confrontation via technology is had and routine becomes fractured. Jonathan finds himself waking in places that aren’t his bed and John stops sending messages. We start to wonder how bad things might get since it appears these two men are spiraling out of control. Dr. Nariman is shown as a maternal figure desperate to help while Elena unwittingly becomes the sole shared point of connection outside their secretive and experimental condition. For forty minutes we become intimately aware of Oliver’s sci-fi conceit through heightened emotions, visual puzzles, and potential betrayals. It’s the perfect set-up for a thriller built on exclusion and yet it becomes much more.

I won’t lie and say this initial third is without problems, though. It can be extremely sterile thanks to Jonathan’s lack of personality and the information overload necessary to comprehend what’s going on without confusion. Kudos to the filmmakers as far as the technical nuts and bolts of their scenario goes because it’s pretty airtight. This is probably helped by the fact that they only have to provide one half of the whole, but don’t discount the difficulty of turning the conditions with which Jonathan wakes up into pertinent, contextually crucial details. Unfortunately such proficiency can be just as alienating as laudable. And since John is barely seen, we’re often left with analytical pragmatism. Only when Jonathan thaws to show comparable feeling does the film really grab hold.

It’s here that we start seeing him as more than an automaton. He becomes vulnerable once John (figuratively) disappears, worried their coexistence might be in peril. Survival becomes more than simply living his own life separately and the reasons for this will prove heartbreaking if you let them. Elena becomes Jonathan’s salvation in John’s absence, but also his potential destruction if his brother discovers they’ve begun a friendship. And Dr. Nariman becomes a more robust part of their story as a seemingly impartial third party with more than scientific interest staked in their success. They initially present as pieces on a game board and as such the film might appear unworthy of your time on first blush. This is wrong, though, once their actions reveal an underlying love.

Jonathan the film becomes two disparate pieces much like its namesake. The first half centers on Elena impacting their relationship, the second on Dr. Nariman. These two women are catalysts who might not ever truly become more on their own, yet what they ignite is critical to the plot progression’s success. Elena conjures jealousy to tear them apart while Nariman reminds them of the sacrifices they’ve endured and the reasons why they’ve willingly embraced them. Jonathan and John must fracture in order to understand the other’s impulses, needs, and identities because they are human and humans lie whether or not they realize they’re doing so. They lie inwardly too about personal happiness and comfort, putting on a brave face wherein they become the victim of their own deceit.

Except the idea of “self” isn’t so simple here. Whereas brothers possessing individual physical forms can co-exist and grow closer with distance, these two aren’t afforded that luxury. They’re instead sitting front row at the other’s demise, unable to give him a hug or share his pain. And since their duality is biological, any change in equilibrium risks throwing a wrench into the system itself. Passion gets weighed against utility; flaws that make one unique against those that hold the other back; and love against self-preservation. The filmmakers lead us to dark places in the process, flipping stigmas on their head to hide the psychological consequences of what’s happening beneath emotional ones. And it culminates in a beautiful expression of melancholic sorrow you never could have anticipated an hour earlier.

Jonathan hits limited release and VOD on Friday, November 16.