Has the hype around a nearly wordless, 54-minute, India-set documentary ever been so high? This is what happens when Paul Thomas Anderson, a not-unpopular choice for the “greatest living American director” label, puts his hands on something. It’s for this reason and this reason alone that Junun, which chronicles the making of an album by regular collaborator Jonny Greenwood and Indian musicians, is already the subject of much discourse and will serve as the launching point for MUBI’s new theatrical-distribution arm. This is generally a modest work, perhaps only requiring a theatrical outlet when it comes to the excellent soundtrack, and Anderson mostly uses its loose framework as a playground for new-to-him forms — the documentary, first and foremost, but also (and more interestingly) the possibilities afforded by digital filmmaking. The images of a far-away land are genuinely curious (never just pretty-looking and postcard-like), the performers making the music at its center are terrific, the work they’ve produced is booming and unique, and, above all, everyone seems to be having a good time. If your expectations call for a new benchmark in his career, you might want to come back down to earth before diving in.

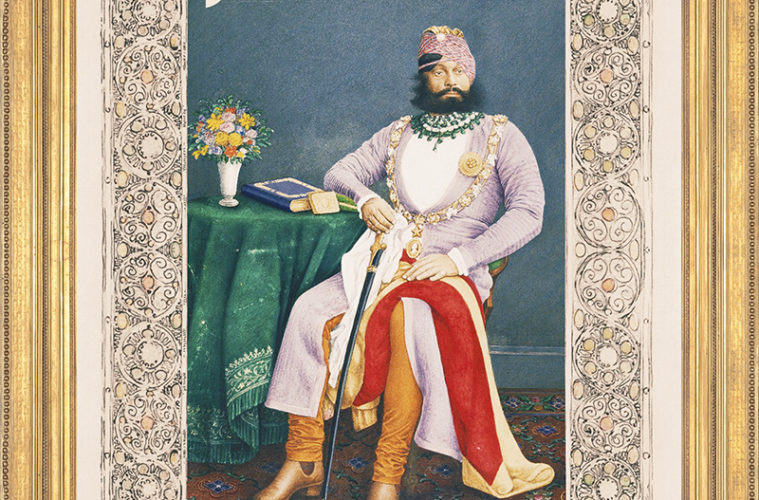

Above all else, Junun serves as a proper hangout movie where we, the outsider, have been invited to watch its talented players sit around as they strive to create compelling, satisfying art. Its calling card is the opening sequence, an intense instrumental performance held during an afternoon call to prayer in Jodhpur’s Mehrangarh Fort: these men, Greenwood the only recognizable one among the lot, are in their element, we’re in their grasp, and Anderson’s fixed, swirling camera clearly wishes to hold that grasp as much as possible. When this forceful introduction was immediately followed by Anderson’s intimate, washed-out digital images, I wondered if we were in store for a major work.

I was also getting a bit ahead of myself. In retrospect, the only real frustration comes from comparing those and other moments of experimentation with the clean-cut, less-than-surprising documentation that largely comprises this project. (The focus on musical performances, Greenwood’s own presence, and the equipment-strewn setting all inevitably drew mental comparisons to one of Radiohead’s From the Basement episodes.) The atmosphere afforded by these shooting locations is never taken for granted — even if said location is a room with a door or window open to the outside world, Anderson will make something of that — yet Junun shines brightest when it’s plunging past the surface to investigate things more ineffable: questions regarding the creative drive of these performers and he, the documentarian, loom large, as does (albeit more obliquely) the way perspectives change when the surrounding hemisphere isn’t your own.

These subtexts are rather snugly joined by the use of digital photography, a territory Anderson is broaching for the first time. These images often boast the solid, stable visual character expected of latter-day technology, thus mostly making them indistinguishable from their physical brethren, and so the greatest surprises — even wonders — are found via the grainier cameras that rove Mehrangarh Fort and capture experiments in time-lapse sequences. Otherwise, performances are shot and edited in a fairly classical style by highlighting everyone included, despite the camera sometimes choosing to focus on a pigeon fluttering around the room or Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich chasing it out with a music-note stand.

Even if it’s a bit shocking when at least some (if not all) of the lower-quality cameras are revealed to be drones, none of this is groundbreaking; it’s just Anderson running free, an artist unconstrained by screenplay, schedule, or budget. The man will sometimes make his presence felt by posing an off-camera question — often ones that that tacitly underline a stranger-in-a-strange-land status — but he almost never appears onscreen, and the one exception that I’m certain of, having been captured by a flying drone, is distant. In the spirit of this movie’s selflessness, Greenwood, ostensibly the second-biggest attraction, is also sidelined. Why should anyone in a collective effort be treated as a special individual?

What Junun leaves us with, then, is an extended collection of small moments: those heretofore noted, brief insights from its stars, some (non-performative) fun with instruments, and, most notably, one musician’s trip into town to tune a trumpet. That the beautiful music at its center can only be reached with the help of an ugly, cheap-looking, battery-powered keyboard helps encapsulate this endeavor entire: sometimes the unpolished and everyday are all we need to create something greater than the sum of its many parts. I question whether or not Junun succeeds at this, but maybe that’s irrelevant when the peculiar place inside Anderson’s oeuvre breeds an additional interest for itself and that which surrounds it. More filmmakers could stand to breathe easy with a minor effort; jam sessions have their place, too.

Junun premiered at the New York Film Festival and is now streaming.