Albert Lamorisse, the talented maker of fantasy short films and the board game Risk (here the game is rebranded as The Arbalest) influences a young Foster Kalt, a dreamer whose invention, despite being dazzling, is laughed at on the eve of its debut in 1968. His proposal is a device that converts oxygen to helium, filling a balloon without a clunky tank. It appears the world, or at least the object of his affection, prefers the Rubik’s Cube.

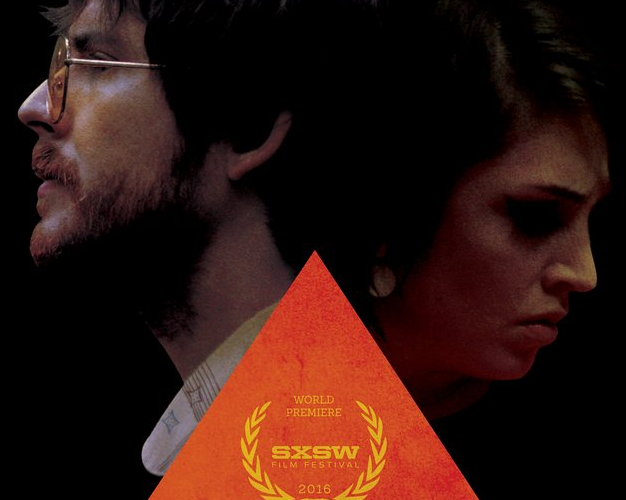

Luckily for writer/director Adam Pinney, The Arbalest is a far more fitting title than Risk. A piercingly original and very funny debut feature, the picture takes no prisoners as it constantly changes shapes and form. Its subject, the elusive fictional Foster Kalt (Mike Brune), is a narcissist who takes aim at those that dare laugh at him — an unholy combo of Donald Trump’s ego and The Hudsucker Proxy’s Norville Barnes’ gumption with the personality of Unabomber Ted Kaczynski, right down to the shack he finds himself held up in for most of 1974. He’s not an easy character to like or pin down, yet he’s one of the more original cinematic creations of the year; a self-made man seemingly without a past, present or future, he gets lucky when the inventor of a fictional cube puzzle ODs on the floor of his hotel room at a toy convention in 1968.

Kalt’s desires aren’t entirely noble. Flipping through a catalogue he wants a sexy partner in crime which he never seems to find despite his wealth and fame. Perhaps even for gold diggers, he’s got one too many screws loose — either that, or his obsession with Sylvia prevents him from getting close to someone else. Let’s back up to 1968.

Foster finds himself in a hotel room with a man in a suit (John Briddell) and Sylvia (Tallie Medel), a travel companion. After a night of drinking the man expires, and Sylvia encourages Foster to scrap his revolutionary idea and pitch the man’s cube game. It turns out to be a hit and the Kalt Kube rockets Foster to A-list status, yet still his life is unfulfilled. Making good on the promise of royalties to Sylvia he starts to send love letters as well — the checks are cashed, the letters are returned.

Foster then takes up residence in a Unabomber-style shed on a property across from Sylvia and her husband John (Robert Walker Branchaud) for much of 1974 before circumstances force him into a monk-like silence.

Jumping between 1968, 1974 and “present day” 1978 where reporter Myra Ney (Felice Heather Monteith) vows to get him to break his silence, The Arbalest hits its stride as a complex character study with notes of the French New Wave, most explicit with its production design. While Wes Anderson has crafted magical portraits of self-obsessed narcissists, they’ve never been quite this dangerously deranged. One has to wonder what would have become of Foster Kalt had he not magically stumbled into success thanks to one magical death by overdose. His reaction to it essentially sums up his theory of life: he tells the operator the man is already dead, no need for the ambulance to rush.

So little is known or justified about Foster Kalt, adding to Myra’s mystery, and the film continues to shock and delight all the way to its final conclusion. Like Willy Wonka, her camera team refuses to believe his inventions are real, much to their own regret as it were. The Arbalest is one of the sharpest black comedies of recent memory, never apologizing or justifying the insanity of Kalt as those around him and the audience watch with morbid curiosity as to what he’ll do next and why.

The Arbalest screened at the Montclair Film Festival.