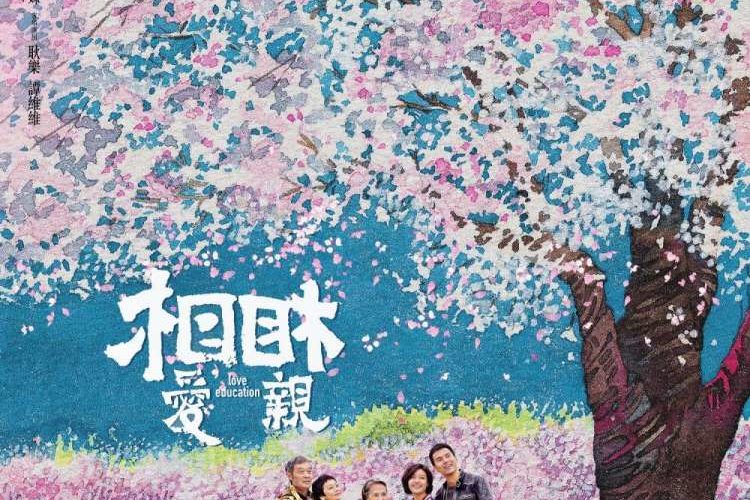

Death is literally the beginning in the cross-generational relationship drama Love Education, which closes the 2017 Busan International Film Festival today. In depicting a quintessentially Chinese family dispute about burial sites that sets free unspoken sorrows building across half a century, it reveals how the idea and expression of love have evolved in a vastly changed Middle Kingdom.

The movie opens with an aged lady on her dying bed. As per the long-standing tradition of cinematic romanticism, the last flashes of consciousness play out in a dreamy, amorous sequence of remembered bliss with her white-haired beau. Somewhat more surprisingly, no profound parting words seem to come out of her trembling mouth when daughter Huiying (Sylvia Chang), son-in-law Xiaoping (Zhuangzhuang Tian) and granddaughter Weiwei (Yueting Lang) gather around to send grandma off in a moment of heightened sentimentality.

This initially insignificant detail proves to be a source of intrigue later on. Because, despite Weiwei’s account to the contrary, Huiying insists that her mother has asked to have the remains of her late husband moved back from the country in order for them to be buried together. As the party of three then travels to grandpa’s home village in an attempt to relocate his grave, it’s revealed that he had married someone else before going to the city, where he met grandma and decided to settle down. Said first wife, “Nana” (Yanshu Wu), who had waited a lifetime only to be reunited with her husband after he’s been sent back in a coffin, now refuses to let anyone take her man away. What follows is a portrait of three generations of Chinese women: a post-war widow, a college-educated working mom, and a worldly, free-spirited millennial, each faced with the questions of love at a different stage in life.

Earnestness best describes the multi-hyphenated Chang, who co-wrote, directed and starred in the film. This hurts her storytelling in the sense that whether emotionally or narratively, things are too readily available to wow. The way she stages and cuts a scene, too mindful of getting the point across, often lacks imagination. Where Ang Lee would have suggested using camera angles and compositions, where (pre-blockbuster) Zhang Yimou would have simply stayed a beat or two longer on an empty stare, she spells out immense sadness, suppressed loneliness or camouflaged insecurity with keener strokes to lesser effect. Although to her credit, there’s such sincerity to the picture you can’t help but feel the warmth. The unexpected bond formed between Nana and Weiwei, for example, is touchingly rendered. What started perhaps out of a teenager’s natural rebellion against her mother eventually grows into a grudge- and age-defying understanding of sisterhood and kindness.

Her level of directorial finesse aside, Chang’s screenplay (co-written with Xiaoying You) is – for lack of a less obvious word – quite lovely. On the one hand, it investigates the monumental changes to a society both inside and out. The scenes where Huiying struggles to get her parents’ old marriage certificate re-issued illustrates a country so violently modernized it barely has time for its past. And the subplot about the television station where Weiwei works creating a spectacle out of her family tragedy, turning Nana’s decades of quiet suffering into a gag on reality TV also shows how far morals have shifted since the days of chastity arches.

On the other hand, the story picks up ancient and post-modern sighs of heartache alike, making a compelling case for our timeless need for love. This could take the form of a retirement-age couple reminiscing about their wilder days and wondering where they’ve all gone. Or a daughter’s desperate conviction that her parents have loved each other, wouldn’t have it any other way than to be buried together. This is a piece of screenwriting that juggles rich ideas and is not afraid to go to intimate places.

Despite being shot by iconic DP Mark Ping Bin Lee and edited by Jia Zhangke’s oft-collaborator Matthieu Laclau, the film isn’t as striking a visual experience as one would hope. A notable exception is the ending. In the city apartment and out in the countryside, things are happening in parallel. Firecrackers light up a memorial procession seen from afar, captured with foreboding majesty. A couple hurries to leave home, their minds set, an urn of ashes in hand. Cut with artful precision, you instinctively synchronize the two and allow yourself to be lifted up by their not-too-subtle message of forgiveness, generosity, and love.

Love Education premiered at the 2017 Busan International Film Festival.