Guilt is a powerful thing. It can make you act in ways that go against your own survival and yet still ensure those actions are selfishly motivated. You aren’t necessarily acting to help another or have their best interests in mind. Your goal is to make-up for something you did previously. It’s about feeling better and feeding a misguided notion that you’re somehow the center of attention—the inevitable bringer of unwarranted pain and suffering. Wars have been fought over guilt. Religions have embraced it as strength. But all it truly delivers is a skewed outlook on responsibility. Sometimes things are simply out of your control. Sometimes an accident is exactly that. Guilt is a destroyer too many just can’t ignore. And it drives us straight towards oblivion.

This concept—along with its twin shame—is central to the plot of Alex Haughey and Brian Vidal’s feature-length science fiction debut Prodigy. These two filmmakers dip their characters into a pool of guilt and watch whether it clings to their skin or falls off. The feeling originates from an age-old question concerning weapons as a means of protection or devastation. With every new breakthrough in technology comes the potential of catastrophic fallout. Advancements can be exploited out of greed and usually are as soon as their benefits get revealed. The atomic bomb is both a means of defense and offense depending on who has his/her finger on the trigger. Control becomes paramount and hard decisions get made. Utilitarianism with a side of remorse proves a volatile cocktail.

The weapon in this context is a young girl named Eleanor (Savannah Liles). Military man Colonel Birch (Emilio Palame) describes her as a menace never to be underestimated, one for which he’s implemented extreme deterrents in case of escape. His counterpart on the case is Agent Olivia Price (Jolene Andersen), someone who’s yet to remove humanity from the equation. They’ve spent a year studying Ellie only to come up empty as far as finding the evidence needed to believe she still has the means for compassion and empathy despite a violent past tilting the scales in the opposite direction. With Birch, psychiatrist Dr. Keaton (David Linski), and biochemist Dr. Werner (Harvey Q. Johnson) ready to give up, Price asks for one more chance to remove Ellie’s sociopathic façade.

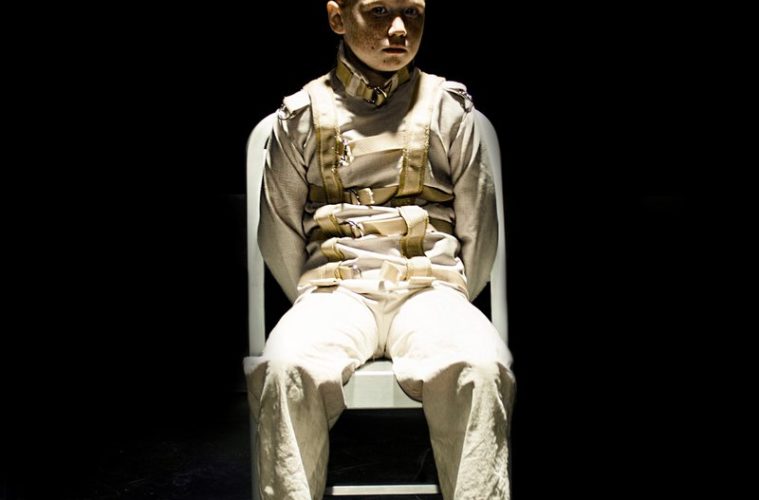

This last-ditch effort arrives in the form of psychologist Dr. James Fonda (Richard Neil), an old college friend of Olivia’s who’s focused his efforts on troubled youths. He doesn’t have the salary for expensive suits or hairstyles. He isn’t pompous enough to diagnose or dismiss a patient sight unseen either. Fonda is very purposefully an outlier willing to enter this case with an open mind devoid of preconceptions. He wants to treat Ellie as a child rather than a threat because the goal is ostensibly to show that’s exactly what she is. The odds of keeping his mind clear are stacked against him considering she’s tied up in a straightjacket to a chair, but he’s going to do his best regardless. He has to. He’s her final hope.

Why then is she so combative? Why is she so keen to use her intellect to provoke rather than appeal? This is a very obvious question anyone would ask and yet the professionals on the other side of the two-way mirror separating them from Ellie and Fonda never did. It’s a realization that causes frustration in the viewer because it presumes Haughey and Vidal purposefully wrote their “experts” as self-absorbed elitists with heads so far up their behinds that common sense is non-existent. So you’ll laugh when Keaton’s eyes are opened by Fonda’s insight. You’ll roll your eyes because the filmmakers haven’t yet exposed what’s really clouding their handicapped judgment: fear. Fonda’s ignorance towards Ellie’s case beyond her being a troubled youth shields him from being afraid.

It’s a crucial pivoting point that Haughey and Vidal willfully risk losing their audience in order to let its impact reach peak potency. The way Fonda becomes Captain Obvious to a room full of smug jerks pairs with the film’s unmistakable independent budget to hit a suspension of disbelief wall from which some viewers may never recover. They should, though, because everything that comes next is worth moving past this shaky start. You soon discover that these “experts” are here to provide Fonda the adversity he needs to embolden himself with the confidence necessary to keep going. Their apparent two-dimensionality is actually a well-manufactured embodiment of fear’s power to render intellect moot. It’s not that they couldn’t help Ellie. Their emotionally driven bid for self-preservation won’t let them.

So Fonda’s discussions with Ellie are of course the highlight of the film. They pit two people against each other who know nothing about the other save what they can see and experience right here and right now. While Price wrestles with the guilt of what happens next if Fonda fails and Birch readies to take a weapon he fears will destroy the world off the table, Jimmy and Ellie start mining the other’s mind to find truths they’ve both hidden away. Ellie’s steely gaze and monotonous cadence purposefully shroud hers; Fonda’s are merely private details he had no reason to share until asked. She pushes him to tell her and he gleans hers from involuntary actions tied up with her intense psychological state. They treat each other like humans.

There’s an inherent cause and effect at play wherein we’re seeing each character through an exterior lens they’ve allowed themselves to be viewed through. This is prejudice and self-hate at work. Sometimes people are so quick to judge and vehement in assumptions that any attempt to change their minds seems futile. If you’re to be punished on the basis of conjecture and circumstantial evidence—on mistrust out of the fear of the unknown—why not embrace it? If you’re to be blamed anyway, why not do something to earn that ire? Why not do things that prove you’re the monster they say (and you now believe)? It’s easier to accept blame and feed hatred than it is to alter an emotion-fueled bias. Welcome to America, circa 2017.

Haughey and Vidal use supernatural powers—the mechanics of which are stunning here considering the low budget—to show how monsters are often created through the act of being hunted. To be vilified is to fight back. This is a core tenet of survival. What’s added to the mix is the existential dread of defeat, of blaming oneself for not understanding or controlling that which he/she never asked to possess. This duality makes X-Men so good: the Rogues of the world learning to live with the “otherness” and danger within themselves. Think of Ellie as young black kids hauled in by police for their skin color. Think of the constant guilty until proven innocent questioning meant to break them, turning them into that which they wouldn’t have been otherwise.

Prodigy screened at the Buffalo International Film Festival.