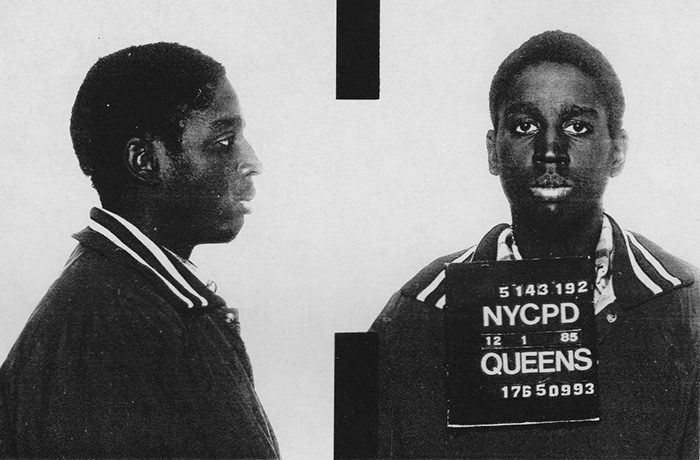

It starts as a lark: Darius McCollum gets led away in handcuffs with a smile from ear-to-ear. We think this is a guy having fun pretending to be a Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) employee. He knows what he’s doing, never hurts a soul, and gets people where they’re going on time whether by subway, train, or bus. But this isn’t the truth of the matter, as director Adam Irving soon reveals in his debut, Off the Rails. Darius has become less folk hero to the state than a career criminal who must be stopped. Stopped — not punished. New York has become disenfranchised by punishment because their target has been arrested thirty-or-so times. So now they throw the book — 15-years-to-life for doing the only thing he knows how.

The issue is made more complex upon learning that Darius suffers from Asperger’s Syndrome. Not only is he therefore not going on “joyrides”; he also can’t help himself from acting on his compulsion. Transportation is his subject of choice — his obsession — and it has been an escape since cultivating fear and mistrust towards his peers in grade school after a horrific incident at a young age. The MTA workers quickly took him under their wing, teaching him the routes and buttons when he was twelve before making him an “honorary employee” at fifteen, unbeknownst to the bosses in control. To hear him tell it, his first arrest was a simple misunderstanding. He was doing what he was told and helping out. But that mistake blacklisted him for life.

Irving is on his subject’s side because you must be upon experiencing Darius’ affable humanity. He’s the product of a failed system, his youthful notoriety as a “hijacker” forcing the MTA’s hands knowing the media circus that would occur if he got someone hurt, regardless of employment status. He became a liability, and you can’t really blame anyone for thinking so. He is meticulous, careful, and cognizant of so much more than career conductors, but he isn’t sanctioned, properly trained, or psychologically vetted by professionals to ensure he can remain stable and true to the chain of command this job utilizes. We can’t therefore blame the MTA for refusing his services. The establishment at fault is New York for never providing him the means to prove his worth.

This man was failed constantly by the school allowing him to be assaulted, the MTA workers treating him like free labor without thinking about the consequences of doing, and his first deplorable fame-whore lawyer who let him stew in jail by skipping his arraignments. The law itself failed him by not allowing wiggle room when it comes to “mental deficiencies” such as Asperger’s. Judicial rhetoric won’t look at things case-by-case because it’s easier to place someone in a neat box without nuance. It tells him he doesn’t have the faculties to make decisions when he does. It takes away what he needs to combat his urges (riding the subway) and forces him into a corner where the rush of stealing the next bus is worth the jail stint.

And as the talking heads Irving puts onscreen explain, Darius never received treatment in his nineteen-plus years behind bars. The closest he got was finding Islam through the Imam at Riker’s Island, so there’s been no reform — just wasted time and taxpayer money. Rather than attempt to fix the problem, the state has exacerbated it at every turn until creating their grand solution of locking him up for good. They refuse to see him under the lens of special needs by pretending he can “just stop when he wants,” and they refuse to treat him like a human being who has something to offer. He has become a statistic: homeless, in-and-out of jail, and unable to kick his habit. Depression makes him crave euphoria and the cycle continues.

What makes it worse is how understanding towards his situation he is. Darius doesn’t lie when caught — he admits he stole the vehicle, uniforms, and keys. But he smiles while doing so. He can’t help himself. Suddenly the prosecution and state take that smile as superiority rather than good-naturedness. They call him a liar, charge him for things they don’t have more than here-say to charge him with, and ignore their roles in destroying him. Irving therefore uses this insane tale of tabloid exploits and internet fame to reveal the judicial system’s faults. Much like Darius assisting the MTA while in jail to help patch up security issues he saw, Irving is exposing the holes in a process built to ensure certain non-violent offenders can never recover.

It’s a captivating experience with wonderful displays of heart and humor, but I must question some of its execution. Irving uses recent events (his latest stint stemming from a 2010 arrest) to serve as a backbone to the whole, but it often arrives out of nowhere as a single line of text before disappearing again. This gets confusing at times because the transitions are so abrupt — is he still talking about that same arrest or a different one now? Where’s this going that he can’t just tell that part of the story together like the rest of the film? By the time his motivations are exposed — family reunion, personal struggles, and the prospect of slipping back — it makes sense. In the moment, however, it felt awkwardly incongruous.

And things can get a bit weird when Darius is narrating. Some instances are funny (his words supplying exacting detail while actors reenacting scenes mouth them), others unnecessary (a cartoon version of Darius mimicking nicely used Superman footage despite being a completely different style). This is one documentary I believe works best when we see people talking, especially with a subject so expressive and genuine. Looking him in the eye when he explains the truth of what happened is crucial to believing his version of the story. When we’re able to do this, we know in our hearts that every word he speaks is gospel. Rather than the liar the state paints him to be, Darius proves a troubled soul who the system transformed into an unwitting example.

Off the Rails played at the Buffalo International Film Festival with a limited release in Los Angeles (November 4 at Laemmle Music Hall) and New York City (November 18 at Metrograph) to follow.