By Bedatri D. Choudhury

There is something about people who give themselves new names; a sense of rewriting their own destiny, a sense of wanting to control things assumed to lie out of our control. Nutan Kumar changed his name to Newton when he was fifteen. He changed the “u” to “ew” and the “tan” to “ton.” That is perhaps when he decided that he had a huge responsibility to live up to — the responsibility of doing things and doing things right.

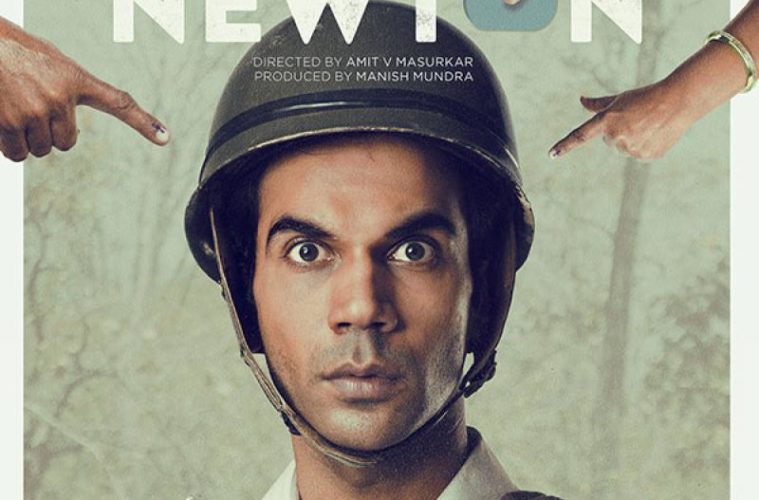

Amit V. Masurkar’s Newton is a story about a do-gooder government employee assigned to conduct elections in a conflict-ridden area in Chattisgarh, the central-eastern Indian state. Anyone familiar with the way Indian bureaucracy works will know the cliches of the lazy government clerk who is late to work, takes long lunch breaks, and leaves early before getting much work done. Not Newton, though. He is different, not because he does great things, but because he just does what he is supposed to do; he reads rule books and does what they ask him to do. Within the functioning of the bureaucracy this is so unheard of that Newton amazes and inconveniences everyone.

India’s Foreign Language Oscar entry is the story of an election booth in Chattisgarh’s Kondanar, whose people are voting for the first time. As should be the case in every democracy, the government sets up a polling booth even in areas where only one voter resides. Kondanar has 76.

Kondanar is also a mineral-rich and human resource-poor place, caught between a three-decades-long armed warfare between the Indian Army and armed communist guerrilla groups called the Naxals. Teamed with a diabetic co-worker who needs frequent bathroom breaks and another who just wanted the free helicopter ride, it is up to our hero to ensure that the elections take place smoothly and fairly. With an already-hostile army offering no help, it is a mammoth task.

Newton is a political film, but it is also a very witty. So there is no lecturing, no overt sloganeering, but only a very wry, ironical take on the way things function in India, and a perhaps a whole lot of other places in the world. Especially striking and symbolic is the scene where the Army officers accompany Newton and his colleagues to the designated polling booth. The diabetic co-worker, Loknath, suddenly needs to use the bathroom and all the Army officers scurry along trying to find a “safe” place for him to relieve himself in the jungle. For the next few minutes, there are election officers and Army officers waiting for this man to get done so that they could begin on starting the polling procedures. It is like a country queueing up for democracy with bated breath, but it first has to wait for a man to finish taking a dump. That silent scene – just government officers sitting and waiting in the middle of a jungle, saying nothing much – sums up everything the film has to say about the absurd, surrealist nature of modern democracies.

When talking of government policies and their facelift, we often just blame things on politicians; it’s the easiest way out of debates. Newton blocks that easy way out; it delves deeper and asks questions that make one uncomfortable. It starts with the statement that politicians are rogues and criminals, and then it holds pretty much everyone responsible for the soup we’re in. It implicates all of us doing (or not doing) our parts to make this democracy a failing system. The government that is quick to introduce a polling booth in Kondanar does nothing to educate the people living in Kondanar about what elections are. The Army that is crying foul about armed militants burns down schools and homes to evacuate villages and force villagers into living in government “shelters.” And before delving into the illiteracy angle, we’re reminded of governments that are constantly trying to push a “national language” spoken by only 40% of the population as the compulsory medium of instruction.

Newton is idealistic to a fault, someone who stands up for what is right, follows the letter of the book and puts his own life in danger. We meet Malko, the school teacher from Kondanar who shares Newton’s vision and admires his strength of conviction, but insists that he also uses sixth his sense to judge things better. When Newton and his co-workers sit in the empty polling booth waiting for people to turn up, we both want votes to show up for the sake of democratic ideals we’ve read in our civic textbooks, but we also know that no election will change anything for them. The film, nevertheless, is also a narrative of hope.

This hope lies in the finale scene. Newton is hurt from a fight with the Army officer at Kondanar but is back at work at the Collectorate, with a brace around his neck, on time everyday. It is here that Malko meets him, on the way back from a meeting at the Collectorate. She, too, hasn’t given up teaching a village of people fleeing their homes. They agree to get tea during Newton’s lunch break. This delayed sense of hope shows two heroes we need, but can barely even preserve.

Newton screened at AFI Fest.