When director Camille Thoman calls the octogenarians at the center of her documentary The Longest Game charming, she’s describing their initial, surface appeal. At a time when everyone’s aging parents and grandparents are proving how out of touch with the twenty-first century they are in politics, biases, and entitlement, these old friends still playing platform tennis every day after decades of competition on their Dorset, Vermont home’s courts reveal the opposite. Beyond their infectious personalities and razor-sharp sarcasm is a sense of melancholic evolution. They’ve somehow found the ability to look back and see their mistakes alongside what truly matters. In retirement they’ve discovered a new philosophy to engage the world with compassion, understanding through experience the errors of a selfish, chauvinistic lifestyle that harbors regret in hindsight.

We notice this through their own words and those of spouses reminiscing how it used to be. We hear it as they remember the past via Super-8 footage and photo albums as well as how they speak to Thoman and producer Elizabeth Yng-Wong (although some of their archaic philosophies still permeate through the latter with ideas on marriage, children, etc.). You may not think a guy as outgoing as Hal Debona would have needed to change all that much until witnessing his lamentation about wasted time. And we’d presume someone like Charles Ams would be tough to transform since stating plain opinions in the guise of cracking jokes is obviously a key component of his personality and yet he did once love forced him to know domesticity’s other side.

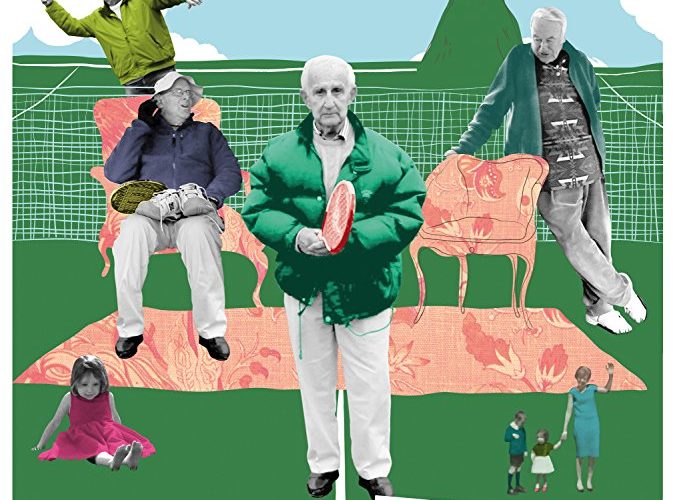

This is the point of the film’s title because it references the game of life rather than a literal paddle tennis match. Hal, Charles, Maurie Warner, Fergus Cochran, Walter Heingartner, and others aren’t engaged in some Guinness World Record ploy, they simply play to stay active. The sport itself serves the role of catalyst because the courts are where Thoman met them while visiting her mother in the same town. From that came an idea of showcasing their perseverance, camaraderie, and eccentricities. From those conversations came the realization that these men had more to offer as exemplars of humanity, mortality, and vitality than what could be culled from their now labored movements around the net having fun. But it doesn’t stop there. Life always carries its little surprises.

Suddenly Elizabeth becomes a main player within the tale as talk about research into her scholar father Quing enters the fray. She has been traveling to Hawaii for that project, her studies into volcanoes providing a poetic through-line for creation, metamorphosis, and life itself. We hear her talk about them and remember stories Maurie told about Mt. St. Helen’s and Mt. Vesuvius. There arrives this sense of kismet wherein those behind the camera and those in front become intertwined by anecdotes, coincidences, and the simple act of conversation. What could have been a straightforward document of adorable old men living their twilight years with activity and laughter becomes a mirror onto just how small the world proves when ego isn’t present to deny the opportunity for discovery.

Thoman splices in archival footage of game shows and silent films relevant to figures mentioned (Harry Endo, Joanne Woodward, and Kitty Carlisle among others), each scrawled upon with an arrow to denote name and age. These demarcations of time, each captured in their present rather than ours, become benchmarks to compare and contrast. They add abstract complexity, historical evidence, and another contextual layer to the whole dealing with the medium of film itself as a means to preserve life. Whether it’s Hal narrating countless hours of years spent as a spectator to his own existence or Charles rifling through old notices of his actress mother Louise Lee, smiling about “sharing” the screen with her a century after her career ended, we’re watching lives long-since over magically unfold again.

Each will become a star moving across the sky as though still there once they’re gone. Why not capture their luminescence while we can? Why not go out of our way to talk to a section of our population too often ignored and listen to the wild stories bouncing around their heads that can both corroborate and dispute the history books? We hope our elders will eventually look to us to remain self-sufficient in an era of speedy technological advancements and fluid social norms, but we forget that we can learn from them too. If it’s not the sense of clarity earned with experience we should aspire towards, it’s the crazy connections binding us together that we’d never imagine existed. Whatever your age, there’s always more to learn.

The Longest Game airs on PBS May 3 (7pm in northeast US) and gets a limited theatrical release on July 26th.