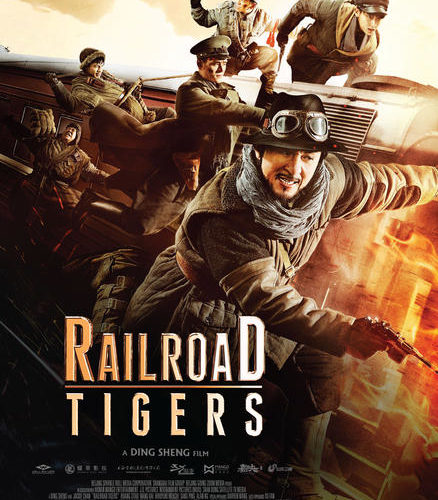

Railroad Tigers is one of those films where, despite its few-versus-many premise, the antagonist often feels like the one with nine lives. That is to say, it is not star Jackie Chan and his small band of freedom fighters who seem like they are surviving by the skin of their teeth, but instead gliding effortlessly through hazardous scenarios. With its 1941 setting in a small Chinese town invaded by the Japanese, this feels like a bit of an anomaly. Yet Chan and company dodge around, knock-out, and dupe their exceptionally silly Japanese oppressors (led by Hiroyuki Ikeuchi of Ip Man villainy) through almost every set-piece and moment of tension, conjuring up images of Buster Keaton or Road Runner. This function makes for some giddily fun scenarios, with wonderful choreography and cartoonish violence, but director and editor Ding Sheng makes the mistake of stuffing his two-plus-hour runtime with unnecessary downtime and bouts of narrative incoherence. This is a shame, as there are moments of slick, joyous entertainment to be had. Unfortunately, the canvas on which Railroad Tigers plays out suggests a sprawling war epic, yet at every turn the etchings on that canvas are those of an action-comedy-caper, making for an often-bloated cinematic experience.

There is a moment near the end of Railroad Tigers where tension is mounting and everything seems to hang in the balance. Our hero is stuck, and all hope seems to be lost. Then, THWAK. A character is shot in the buttocks and starts hopping around, shouting “that hurts!” The serious, tense music is replaced by a whimsical flute and childish marching beat, and then we are treated to a bit of a save-the-day war montage to cap it off. You will know if the film is for you if the above description makes you laugh or sigh, for it is a rather apt summary of Sheng’s stylistic approach and attempted tonal balancing act. It tries to strike an over-the-top, jovial mood despite its structural foundation, at times conjuring ideas of The Expendables, where nothing is too serious and danger isn’t a whizzing bullet, but the thought of not uttering a one-liner.

This style seeps its way into aesthetic choices as well, where Sheng adapts strange editing techniques that diverges from the traditional cinematic weaving: Snappy fades often transition scenes, and characters are introduced with Tarantino-style title cards, complete with their catchphrases. The cutting is extremely economical in one narrative sense, summarizing some plotting with a single cut. This hypothetically allows Sheng to cover a lot of diegetic time quickly, getting to the action and keeping his film moving at a nice, lean clip. Sadly, this approach only emphasizes the bloat, making it all the more head-scratching as random snippets of dialogue and small sight-gags fill time without really building character or environment.

Bookended by a present-day segment where a small boy ditches his school field trip as we are transported through an animated opening credit sequence and into Chan’s world of Japan-occupied China in 1941, this set-up gives the entire rest of the narrative a sort of chapter book sensation, where one could attribute potentially jarring stylistic choices from Cheng as just adherence or emphasis on that idea. When viewed through this lens, the quick-fades almost feel like pages of the book being turned, and the title-card introductions of characters like side-panels in a colorful kid’s book. Supporting this theory is the literal chapter titles that pop up — such as Rob The Train, Getting the Explosives, and The Great Rescue — which foreshadow the subsequent sequence of events. As such, its cartoonish treatment of violence comes across as a product (or symptom) of its in-world presentation: a child’s fantasy or story. This sort of romanticization or farcical approach towards a harsh, brutal period of occupation could also be seen as a mechanism of coping or study, similar to the approach in works like Closely Watched Trains, where humor masks the uneasy and dark environment of history.

Tigers shines most exceptionally when playing to the strengths of its leads and accepting its humorous nature that should be mirrored by its structural focus. By far the most rapturous sequence is when Chan and another freedom fighter (played by Chan’s son, Jaycee Chan) attempt to steal a set of explosive packs from a warehouse. With attempt being the key word, their aspirations of a stealthy getaway crescendo into a hilarious and tense balancing act, with mistakes leading to triumphs, which of course dip them into deeper trouble again. This back-and-forth, action-versus-obstacle frame is when the film feels at ease and in its element. It is almost cinéma pur, with both Chan’s using hand-signals and ropes to communicate as they try to outsmart the Japanese soldiers in an increasingly absurd scenario. It is a delightfully tactile sequence, allowing viewers to sink into the moment-to-moment tension without ruining the film’s quick clip. Stylistically, and perhaps maybe just coincidentally (based on much of Cheng’s structural interest), the cinematography and editing feel most confident and comfortable here as well.

Sadly, Cheng is often too interested with all of his narrative threads to just allow the action and fun to unfold. While a director should have bigger things in mind than just action, even on an action canvas, the rest of the film often feels half-hearted or perhaps just half-fleshed out. Many narrative beats bump along clumsily, despite its quick visual pace, making potentially effective character moments feel jarring. In the end, Railroad Tigers feels like it could use another heavy pass in the editing booth. Hardcore fans of Chan and his splendid choreography will find moments to delight in, but casual fans may want to find another track to Chan’s better efforts.

Railroad Tigers opens in limited release on Friday, January 6.