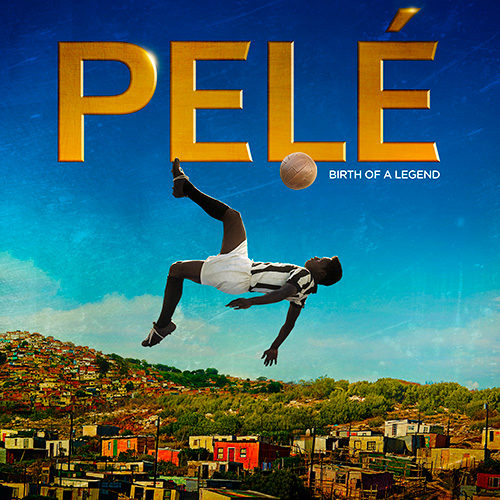

It may be called Pelé: Birth of a Legend, but Jeff and Michael Zimbalist‘s film is really about Ginga soccer and Brazil at risk of losing its soul. The climax depicts the 1958 World Cup with the country’s unexpected run to the final on the back of a seventeen year-old hobbled by a sprained knee, but it’s not his goal scoring that inspires confidence. His ability to run around the pitch in complete ignorance of the Europeans’ formation game lights a fire that burns deeper than technique. Vicente Feola (Vincent D’Onofrio trying a Portuguese accent) was hired to rebrand the team after a debilitating loss in 1950 and poor sportsmanship in 1954 by invoking that European way, but Pelé (Kevin de Paula) refused to forget his identity.

Ginga goes back to the African slave heritage of Brazil’s black community — explained as a fighting style and spirituality all but outlawed outside the soccer field. Players adapted the martial arts-like movements and created what many today call “the beautiful game” by advancing the ball through the air rather than on the ground. It’s really a miraculous sight to behold and a far cry from the style of play many believe is synonymous with a sport labeled “boring.” Thanks to Matthew Libatique‘s cinematography and a cast of skilled futboleros we’re able to witness the majesty ourselves either amongst hanging sheets and steel roofs of Pelé’s hometown, the aristocratic décor of Sweden’s palatial World Cup hotel, or the field opposite an opponent unable to stop the gamesmanship.

The visuals are this film’s greatest asset because it’s hard to ignore the plot’s pitch-perfect underdog striving for victory against dissention from outside and within clichés — whether what’s depicted is fact or not (Edson “Pelé” Arantes do Nascimento does produce and cameo, so I’m assuming it’s close). Between the slum shoe-shiner to soccer hero trajectory, tragic death propelling change in work ethic, and villainous rival turning inspirational friend, Birth of a Legend feels like a made-for-TV special. But whenever the tone turns saccharine or the action becomes prototypically motivational, Libatique finds a way to deliver the imagery with intrigue and beauty. Sunflares while juggling fruit, dried dirt exploding on impact in slo-motion, or precise close-ups of on-the-field dribbling all add up to some rousing sports-fueled excitement.

If the archival footage of Pelé during the end credits is any indication, the Zimbalists’ soccer choreographers took pains to render these jaw-dropping maneuvers as true-to-life as possible. Watching de Paula effortlessly sweep the ball 360-degrees past three defenders for a no-look backheel pass is magical. There were probably more cuts than I’d like for a smooth sequence, but everything fires in impeccable tandem to force my memory into believing I saw it in real time. That’s a credit to my investment in the story because sometimes it only takes being drawn into the action for it to appear live and without fabrication. I knew who’d win the championship and whom the star was, but I stayed on the edge of my seat to watch how nonetheless.

As far as Pelé’s evolution and the lengthy stretches of time spent back home with Mom (Mariana Nunes‘ Celeste) and Dad (Seu Jorge‘s Dondinho): it can get overly sentimental. The latter wants Pelé to go to school and find a way out of the city, the former stays quiet because he knows what soccer did to him after a successful career ended in a bad knee and a job cleaning toilets. The boy (played by Leonardo Lima Carvalho circa 1950) simply wants to have fun. A scout sees him and offers an opportunity; his parents let him squander that chance until they’re finally ready to let him go and build upon his potential. It’s all rallying cries afterward as a nation awaits his greatness. Trials and tribulations commence.

The family stuff is heartwarming; the team comradery by-the-numbers with obstacles (D’Onofrio’s coach, Diego Boneta‘s smug striker José Altafini) and encouragement (Milton Gonçalves as Brazilian ex-player Waldemar de Brito and the Ginga-proficient teammates). Pelé has a lot of fear about losing his spot on the team if he doesn’t try to play like his coaches want, but bottling up that natural talent becomes a crutch risking a catastrophic loss like the one suffered by his father. The mirroring can be heavy-handed and the turnabouts on Ginga versus European strategy too swift, but the plot does have to advance somehow. Luckily for us de Paula proves a charismatic lead to empathize with during the tough times and embrace with an infectious smile during the good.

Birth of a Legend exists on the same level as Miracle‘s portrayal of 1980’s gold medal-winning US Olympic hockey team (there’s even a match against the Soviet Union to boot). This type of story targets a specific audience and those averse to it won’t find anything here to change their minds. The Ginga/spiritual culture aspects are a welcome addition to the usual biography tropes and Pelé being so ubiquitous a name for soccer fans and detractors alike does lend a mystique beyond the sport itself. But while all that is handled business-as-usual, the aesthetic propels it above mediocrity. Libatique isn’t messing around and his involvement is proof that the movie shouldn’t be dismissed. The cinematography got my attention and Pelé’s artistry (re-enacted or not) earned my emotional investment.

Pelé: Birth of a Legend hits limited release on Friday, May 13th.