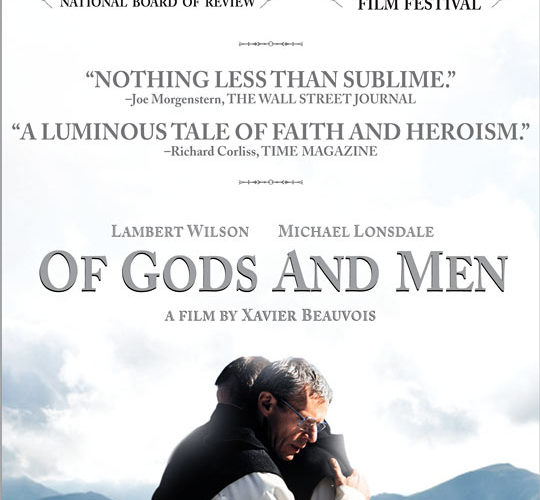

In a time where much of our modern politics revolve around the fear of terrorism, it’s little wonder a film like Of Gods and Men proved so popular in its native France. This drama centers on a group of French Christian monks who chose to remain in their assigned monastery in Tibhirine, Algeria, even when roaming terrorists made doing so, a death sentence.

Loosely based on real monks who were stationed in Algeria from 1993-1996, Of Gods and Men has lofty ambitions, striving to tell a tale of faith and bravery. However, as men of prayer and peace are not prone to shouting or even teeth gnashing, this is a drama very low on conflict. This Spirit and BAFTA-nominated feature unfolds in a purposefully pensive pace, slowly introducing the brothers and their Muslim neighbors, townspeople who depend on them for guidance and medical care. It’s an idyllic world of laughter and goodwill until a group of Muslim extremists begin slaughtering foreigners and even locals they deem indecent. Soon, these men of meditation begin to debate (at length) whether they should stay, even if it means being murdered, or instead flee to their native France, where they would be safe. These discussions, always presented with measured-tones and even-tempers, make up much of the film’s conflict. Which is to say, despite the looming threat of violence and murder, this is a narrative that lacks bold dramatic scenes.

The main problem is the film’s protagonist: Brother Christian, a man so unflappable in his faith that he resolutely resigns himself to martyrdom during the first act. For the rest of film, his goal is just to bring the others to this same kind of lamb-to-the-slaughter mindset. It doesn’t allow for much of an emotional journey or character-changing arc, and so the film drags on from scenes of chanting and prayer, to scenes of unspoiled countryside, to scenes of old men discussing life and death matters in calm and patient tones. When the final credits reveal the grim fates of the men on which the characters are based, it rings hollow and anticlimactic as this was the ending Brother Christian had stoically been prepping them—and by extension us—for since the first frame. Ultimately, this docudrama depends too heavily on its “real story” basis, as the characters are not well-defined enough to prove captivating. Instead, you’re left to coach yourself that these were real people, so you should feel sad. Right?

Beyond that, the reason these monks choose to stay is because their neighbors depend on them. Yet the film quickly forgets these native characters, leaving their potential plot lines dangling without resolution. It almost makes it seem that the filmmakers found these North African natives worthwhile only in so far as they show how courageous and self-sacrificing their white neighbors are. Aside from being thematically off-putting (to say the least), it’s further disappointing as these tertiary characters were more lively and colorful than the mellow monks, and thereby much easier to take an interest in. When they fade into the narrative’s background, I likewise felt my interest ebb.

Ultimately, Of Gods and Men is another docudrama that aims to paint a portrait of courage and conviction, but falls flat as its hero is too good to feel relatable. It repeatedly and purposely sidesteps scenes of dramatic conflict, even acknowledging but never exploring French imperialism as part of the roots of this wave of terrorism. By casting off scenes of conflict in favor of a potentially more realistic portrayal, the proceedings are left with a lackluster gloom as these martyrs march toward certain death. In the end, Of Gods and Men is about as thrilling as the droning hymns sung throughout.

Of Gods and Men opens in limited release February 25, 2011.