Our first roundup of 2025 features some major releases; given the state of things, we should be very thankful for that. Note that our next column will include a lengthy list of new and recent novels and short fiction (one highlight is a short story collection from Burning director Lee Chang-dong) as well as noteworthy Blu-Ray and 4K releases from Criterion and Warner Home Entertainment. In other words, plenty to get lost in––thank goodness for that.

But before then, we have the following terrific texts, starting with an extraordinary biography of one of our greatest living filmmakers.

The Magic Hours: The Films and Hidden Life of Terrence Malick by John Bleasdale (University Press of Kentucky)

John Bleasdale’s Magic Hours is, remarkably, the first in-depth biography of Terrence Malick. This in itself makes the book a crucially important release. Indeed, this is an essential book on cinema, one written with intelligence and personality (Bleasdale opens with a visit to Malick’s childhood home and the real Tree of Life), bursting with fascinating details (we finally have the definitive account of the 1995 Thin Red Line table read, and also learn of an early-70s meeting between AFI classmates Malick and David Lynch, and critic Pauline Kael), and deeply probing. We discover how Malick’s complex and difficult relationship with his father, the death of his younger brother, and his love of philosophy (and Texas, for that matter) has influenced every step of his career. Magic Hours ends at our current moment, as the world awaits the debut of The Way of the Wind, Malick’s ambitious “series of scenes from the life of Jesus.” Might this be the director’s boldest move yet? “Heading toward his eighties, Terrence Malick was still outside, being in the world, going on location, moving around with his rock group.” How fitting it is to think of Malick always on the move, always experimenting, always dreaming up something the world has never experienced before. Perhaps the greatest achievement of The Magic Hours is that it reminds us how lucky we are that Terrence Malick is alive, well, and working.

Louis B. Mayer & Irving Thalberg: The Whole Equation by Kenneth Turan (Yale University Press)

With The Whole Equation, venerable former Los Angeles Times film critic Kenneth Turan has crafted a hugely enjoyable read centered on two key figures in Hollywood history. The friendship and eventual rift between Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg is the subject of this unique joint biography. While both men are compelling, it is the mercurial Mayer who most intrigues. “Like the high-volume Automat eateries,” Turan writes, “he was aiming for quality but only if it could be mass-produced and scaled up.” His office was enormous (“You need an automobile to reach your desk,” said Samuel Goldwyn), his adoration of the Andy Hardy films off-kilter, and his influence vast. Mayer and Thalberg were giants; Turan vividly captures the period of time in which they walked the earth.

The Chateau Marmont Hollywood Handbook edited by André Balazs (Rizzoli Universe)

The backstory of this collection of rare writing and behind-the-scenes photos is captivating. Edited by legendary hotelier André Balazs, the book has been published again for the first time since 1996. Inside is text from the likes of Lillian Ross, Budd Schulberg, Dominick Dunne, and Jay McInerney, along with photographs of, well, nearly anyone who was anyone in Hollywood. Favorites must be the Annie Liebovitz shot of a bald, bare-chested Dennis Hopper and long-haired Christopher Waken; a shirtless Humphrey Bogart “tending to the bungalow garden”; and a smiling Björk moving “between rooms,” photographed by Spike Jonze. What joins it all together, of course, is the hotel. The Chateau Marmont is the most important character here.

Falling in Love at the Movies: Rom-Coms from the Screwball Era to Today (Turner Classic Movies) by Esther Zuckerman (Running Press)

Esther Zuckerman’s writing is consistently delightful. She follows up the entertaining Beyond the Best Dressed and A Field Guide to Internet Boyfriends with the fitting-for-February Falling in Love at the Movies. This easily digestible guide to romantic comedies is divided into categories like “The Meet-Cute,” “The High-Maintenance Woman,” “Not So Happily Ever After,” and “LGBTQ+ Love.” Zuckerman explains in her introduction that the book is “a selective history. It’s by no means comprehensive.” Still, she manages to include such deep cuts as The Watermelon Woman, Palm Springs, and the tremendously underrated Joe Versus the Volcano. I consider Falling in Love at the Movies plenty comprehensive.

George Cukor’s People: Acting for a Master Director by Joseph McBride (Columbia University Press)

We have reached the point in which film historian Joseph McBride can be considered a titan in his field, just like many of the greats he has covered in print––a list that includes Orson Welles, Frank Capra, John Ford, and now George Cukor. McBride’s latest, George Cukor’s People: Acting for a Master Director, takes a unique approach to the director of The Philadelphia Story and My Fair Lady. The author focuses on Cukor’s actors, and in doing so brings new insight to the work of a man who is “widely admired but little understood.” It’s always a joy to read about Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant, and James Stewart. But the section I found most enticing is McBride’s look at Justine, starring Anna Karina and Dirk Bogarde. “I always have a special place in my heart for a film maudit,” writes McBride––an apt word to use for this one. McBride finds that the film tells us much about its creator. “More than any of his other films to date, Justine partakes of both sides of Cukor, the man of worldly elegance and the man acquainted with the secretive, louche side of life.”

Blazing Saddles Meets Young Frankenstein: The 50th Anniversary of the Year of Mel Brooks by Bruce G. Hallenbeck (Applause)

It’s pretty incredible that Mel Brooks released his two greatest films––Blazing Saddles and Young Frankenstein––in the same year. In Blazing Saddles Meets Young Frankenstein, author Bruce G. Hallenbeck explores the making of each film, grappling with their impact on cinema and pop culture. “One thing is for certain,” Hallenbeck writes. “Blazing Saddles could only have been made in the free-wheeling, anything-goes decade of the 1970s, an era when hard-core porn could be shown in a mainstream theater and political correctness was years in the future. Young Frankenstein’s slightly gentler humor is still very much of its time and, while a similar film could be made today, the fact is, it’s a spoof that has never been bettered.”

Quick hits

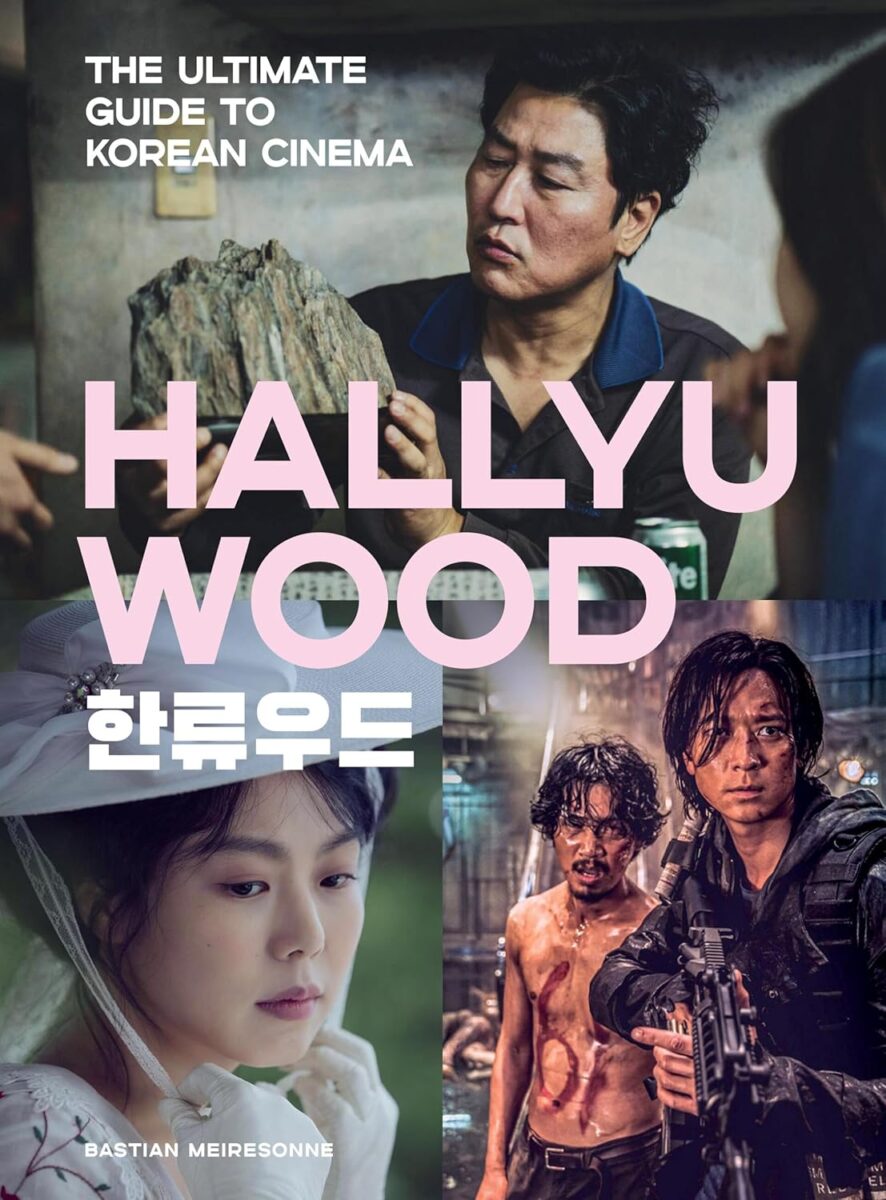

With Parasite celebrating its five-year anniversary by screening in IMAX and with Bong Joon Ho’s long-awaited followup, Mickey 17, finally coming to theaters, it’s a good time to ponder the greatness of Korean cinema. Hallyuwood: The Ultimate Guide to Korean Cinema by Bastian Meiresonne (Black Dog & Leventhal) is an impressively comprehensive exploration of the entirety of Korean motion pictures, from 1900 to the present.

Another impressively researched compendium, this one on a very colorful figure in film and television history, is The Fantasy Worlds of Irwin Allen by Jeff Bond (Titan Books). The “Master of Disaster” produced box-office hits like The Poseidon Adventure and The Towering Inferno as well as beloved TV series such as Lost in Space and Land of the Giants. This book covers it all––even his epic flop The Swarm. “Allen’s seemingly foolproof formula for successful disaster movies seemed to break down with The Swarm,” Bond explains, but Allen’s career was nevertheless quite impressive.

Critical acclaim came much easier to the team of director James Ivory, producer Ismail Merchant, and screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. Following the recent release of the Merchant-Ivory documentary is Laurence Raw’s Merchant-Ivory: Interviews (Conversations with Filmmakers Series) (University Press of Mississippi). The book begins with a joint interview featuring Ivory and Merchant in 1968; humorously, Ivory is asked if he would ever adapt A Passage to India––famously filmed in the 1980s by David Lean––and responds, “I would never dream of it.”

Another enjoyable look at European cinema is Hollywood on the Tiber by Hank Kaufman and Gene Lerner (Sticking Place Books). Originally written in the 1970s, Tiber is a memoir from Kaufman and Lerner, both agents / managers during Rome’s Dolce Vita era. Their memories of Anita Ekberg are particularly moving.

Hollywood Blackout: The Battle for Inclusion at the Oscars by Ben Arogundade (Cassell) is a timely study of the fight to change the Academy Awards’ long system of exclusion, including the stories of Black, Latino, Asian, South Asian, and indigenous men and women.

James Dean and his final film, Giant, are the subjects of two new books. Jimmy: The Secret Life of James Dean by Jason Colavito (Applause) is a fine, juicy reassessment of iconic star, while Giant Love by Julie Gilbert (Pantheon) is an engrossing account of how Edna Farber’s novel was made into George Stevens’ 1956 epic.

Hard to Watch by Matthew Strohl (Applause) is described as a “guide to expanding your horizons,” and the author nicely details the pleasures gained from watching “difficult” cinema. He also reminds us that revisiting movies can be a game-changer: “The last time I watched Jeanne Dielman, I wasn’t bored for a second. That was not at all the case the first time I watched it, two decades ago. The movie hasn’t changed; I have.”

Didion and Babitz by Lili Anolik (Scribner) is a complex but revelatory look at the lives of author Joan Didion and writer-artist Eve Babitz, while Kliph Nesteroff’s Outrageous: A History of Showbiz and the Culture Wars by (Abrams) offers an incisive commentary on comedy and controversy.

Readers interested in how a TV series becomes an international phenomenon will find much to chew on in Believe: The Untold Story Behind Ted Lasso, the Show That Kicked Its Way into Our Hearts by Jeremy Egner (Dutton). There is no question that this is the definitive look at the Jason Sudeikis-starrer. And Kate Winkler Dawson’s The Sinners All Bow: Two Authors, One Murder, and the Real Hester Prynne (G.P. Putnam’s Sons) is an absorbing historical read about the young woman who was the inspiration for Nathaniel Hawthrone’s The Scarlet Letter, and whose death inspired America’s first true crime book.

New music books

As a young teenager seeking to understand the explosive power of punk rock, no book hit me harder than Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming. Savage provided the crucial context for what made the punk movement in the U.K. so vital and necessary. England’s Dreaming was a triumphant achievement that Savage has now equaled with The Secret Public (Liveright). The book’s subtitle succinctly captures the theme: “How Music Moved Queer Culture From the Margins to the Mainstream.” As Savage explains, he is “not attempting a definitive survey of gay culture in pop music; rather, I aim to focus on its influence as demonstrated through five particular moments in history.” Starting with Little Richard and Johnny Ray, Savage then moves through the 1960s and 1970s (David Bowie might be the key figure in The Secret Public), culminating with the life and death of disco. The book concludes with the sight of the inimitable Sylvester and the cover of his 1979 album Living Proof. Savage describes the cover as “a mixture of ages, genders and races” with gay men prominent: “They are relaxed, open and confident in who they are, they no longer have to hide.” I will not spoil the final sentence, a line of such haunting beauty that it leaves the reader breathless and near tears. Such is the power of The Secret Public.

Also powerful is Neko Case’s memoir The Harder I Fight the More I Love You (Grand Central Publishing). This is a sad, witty accounting of childhood poverty, complex relationships, and success. It’s filled with harrowing moments, but ultimately leaves us with great appreciation for what the singer-songwriter has been through and how it’s fueled her music in what she calls the “ever-changing river” of life.

Long Live: The Definitive Guide to the Folklore and Fandom of Taylor Swift by Nicole Pomarico (Running Press) is a fun addition to the growing library of Taylor Swift tomes. Pomarico brings a light but insightful touch to this career overview that chronicles each era, from Taylor’s self-titled debut through The Tortured Poets Department. Even if you are a Swiftie who missed out on seeing The Eras Tour in person––like me, dammit––you will find lots to enjoy in Long Live.

David Bowie All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track by Benoît Clerc (Black Dog & Leventhal) is another book about Bowie, but one that’s utterly indispensable. Weighing in at more than 600 pages, All the Songs runs through Bowie’s entire life, song by song and album by album. While his films do not warrant separate entries, most are mentioned in relation to his musical output. (What, no Linguini Incident?) Structured similarly to Black Dog & Leventhal releases on the likes of Elton John and Dolly Parton, this is a book that does not need to be read chronologically. Open to a random entry like “David Bowie Narrates Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf” and dive right in.

Finally, the latest entry in the 33 ⅓ series of books on significant albums is Kate Bush’s Hounds Of Love (33 ⅓) by Leah Kardos (Bloomsbury Academic). Reading about Bush is always pleasurable and exhilarating, both feelings conjured up by the great Hounds of Love. Kardos goes into detail on the album’s genesis and influences while highlighting the remarkable worldwide success of “Running Up That Hill (A Deal With God)” in 2022 after its use in Stranger Things. “All evidence suggests Hounds of Love will continue to remain relevant, resonant and alive,” Kardos writes. “Its message of love’s triumph over pain, isolation and darkness is something we need to hear, to feel, now more than ever.” Amen to that.