The first image in Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth is of three ravens hovering through foggy and filthy air. Their altitude suggests the camera craning its neck, peering up at the foreboding winged figures circling through the white sky. Or is it really looking down upon them? Moments later, the clouds dissipate to reveal the charred ground beneath, a bird’s-eye view of disorienting perspective. Indeed, like these flying prophets incant the Scottish play’s opening meters, fair is foul, and foul is fair—and within the cloistered halls and barren walls of this lean, stripped-down, resonant adaptation, everything eventually reveals its two-sided nature, its light and its dark.

Gravity eventually attracts those three ravens, which plummet to earth and re-form themselves into the contorted shape of a witch (Kathryn Hunter), whose menacing words, Gollum-esque movements, and haunting tripartite reflection cast a doomed spell on the movie and its ambitious hero. Like Hunter’s alternating corporal and spiritual performance, Coen navigates this particular Shakespeare tragedy between the staid nature of the stage and cinema’s multidimensional freedoms. As though inspired by Orson Welles, whose 1948 version shares a similar duality, he constructs a kingdom in abstracted black-and-white and a squared aspect ratio, surveilling his play from ceilings and steep ledges and pushing into the faces of his shadowed protagonists, perhaps searching for answers they don’t have.

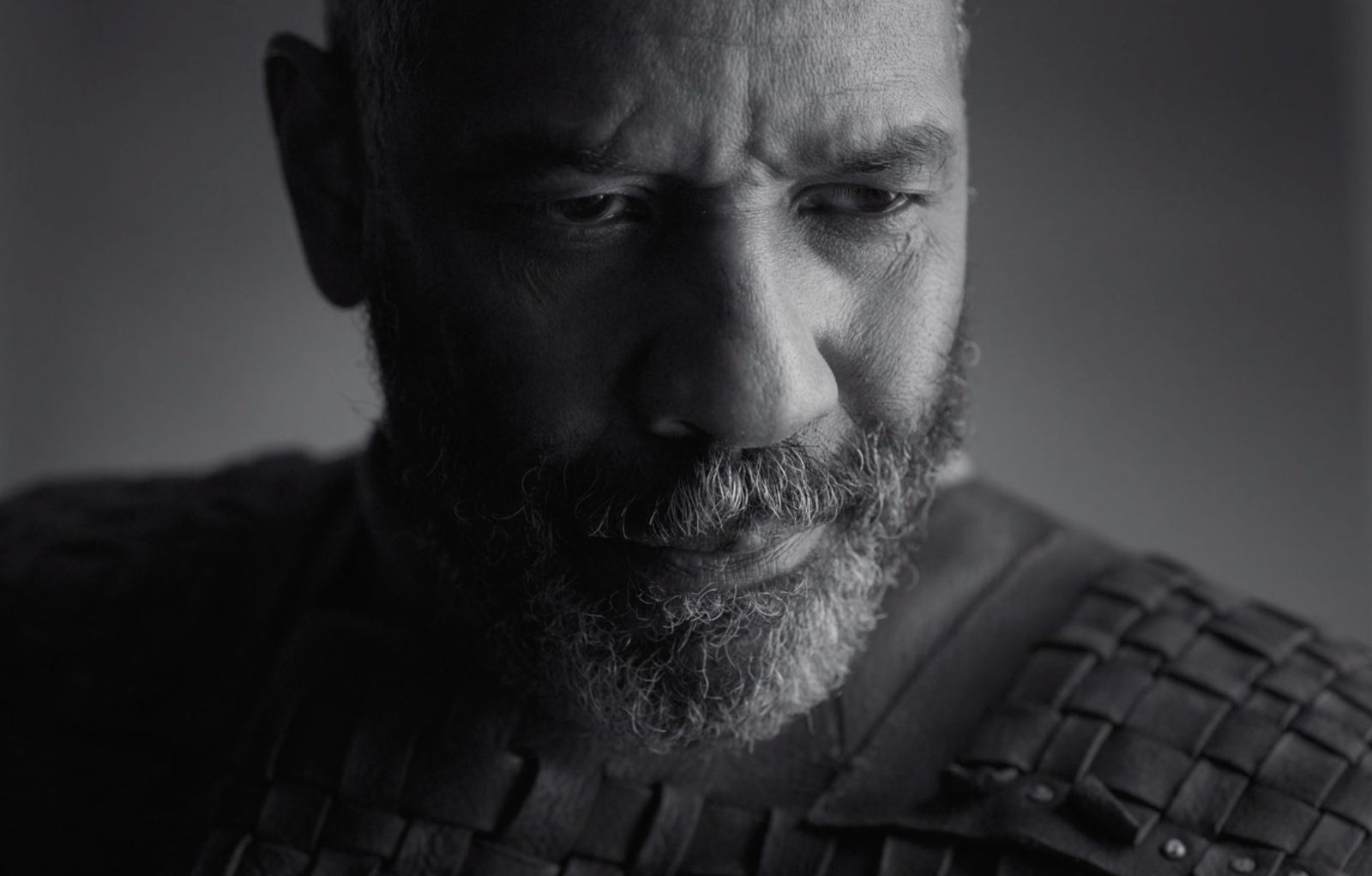

The primary question for adaptations—especially with Macbeth, which has been reinterpreted more than two dozen times on the screen—is why? Sometimes it is to modernize––like the Rock ‘n Roll fast-food oddity that is Scotland, PA––or, if you’re Welles, it’s to recite one last play with his remaining bellicosity. The answer here seems to be a simple one: Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand, two theatrically-trained titans whose age and world-weariness stoke the urgency that Macbeth and his Lady so desperately feel when royalty eludes them. Unlike previous entries featuring younger Thanes of Cawdor, this is a movie indebted to its salt and pepper and weary protagonist, with a wife wary of the alarm clock and the political forces at work. Once Macbeth learns of his prophecy to assume Scotland’s throne—to murder King Duncan (Donald Gleeson)—the blood-soaked machinations for its fulfillment swivel between desperation and apathy. Near the end of their lives, after enduring so many hardships with little reward, this pair would rather go down swinging. What’s to lose?

Of course, that reckless ambition eventually sours and frays at the seams, a careful crumble that Washington vulnerably and forcefully descends. Much of his career has been buttressed by strong, commandeering men, whose confidence erupts through his signature smile, even in anxious times, which smoothes over the whispers that erupt into his sturdy speeches. Though his smile isn’t as wide, there’s a similar wax and wane in the decibels of his soliloquies throughout The Tragedy, in which he chews up the iambic pentameter in hushed fears and then, once the scorpions and visions invade his mind, into chaotic tempers. They echo through a labyrinthine castle, the architecture—never seen from the outside—exaggerating his soldier’s scrambled decay into madness.

In effect, Lady Macbeth must keep up the noble facade of her traitorous husband, who she’s pushed into a minefield she’s ill-equipped to steer him through. McDormand has always had an agitative streak in the Coens’ movies—whether in Blood Simple, Fargo, or Burn After Reading, she can’t quite let things go, no matter the consequences. That cunning, intrusive persistence pops up again, tidying her husband’s murders and fainting melodramatically in front of Malcolm (Harry Melling), Duncan’s son and heir, as they hear of his father’s death. Within Coen’s screenplay, which omits occasional passages and scrupulously tweaks punctuation (McDormand answers the question “If we should fail?” in the affirmative to dynamic effect), her bunned hair, hissing greed, and soft-spoken public niceties provide full contrast to her unraveled climax, which seems to all but lurch from her throat.

This is the first movie Joel has directed without his brother, Ethan, but the movie still feels thematically indebted to their four-decade career as filmmakers together. In many ways, Macbeth itself feels like a template for the pair’s genre storytelling, following characters that commit crime, hide the evidence, and skirt around a conspiratorial landscape until the paranoia catches up. Even Bruno Delbonnel, who captured Inside Llewyn Davis’s frigid isolation and the vast wilderness in The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, returns as the cinematographer, and you can feel the atmospheric after-effects—the chiaroscuro and expressionist shadows bounce off the barren interiors, making it nearly impossible to recognize the Los Angeles soundstage that encapsulated its creation.

Luckily Coen has ample, capable actors to furnish these empty, angled rooms. There is Bertie Carvel as the curious Banquo, and a sharp Corey Hawkins as Macduff, struggling with his paternal regrets. He’s left home his wife and son, whose perilous fate is made memorable thanks to Moses Ingram and Ethan Hutchison, respectively, the final motivation to end Macbeth’s scheming and unchecked leadership. By then, Carter Burwell’s score—led by growling cellos and then loud clangs, bloody drops, and tick-tocks—all but turns this drama into a full-blown countdown thriller, complete with a parallel editing structure towards its finish that enhances the sound of its characters’ demise.

It’s riveting stuff, to the point you almost want Coen to keep pushing the scope just to see where he’ll go. He resists those urges, never wavering from Shakespeare’s language, structure or rhythms. It’s hard to make the Bard’s words feel both meaningful and urgent, but Coen has mostly supplied those qualities, leaning on actors that break the contrivances of their craft, and filling in the gaps with the kind of existential imagery and comedic dread that serve as the foundation for A Serious Man and The Big Lebowski. That includes his expansion on the character of Ross, a loyal nobleman whose moral compass spins a new direction each day. As played by Alex Hassell, he is a survivor, meddling and aligning himself with whomever he believes will keep him in power. It’s an all-too-relevant kind of character, lacking any inner valor, and one Coen suggests might be the greater evil of this well-tread tragedy.

The Tragedy of Macbeth opened the 59th New York Film Festival and arrives in theaters on December 25 and Apple TV+ on January 14.