Widely considered one of the most important and prolific film critics in America, Jonathan Rosenbaum began his career in the 1970s writing film criticism for Sight and Sound, Film Comment, and the Village Voice before becoming chief critic of the Chicago Reader from 1987 to 2008. At the Reader, he published over 5,000 reviews and columns; now, Jonathan runs his own website where he publishes old and new capsules. He is known, among other things, for being a champion of independent and international auteurs and for writing about them in a highly accessible yet personal, erudite style. Jean-Luc Godard once likened him to André Bazin and James Agee.

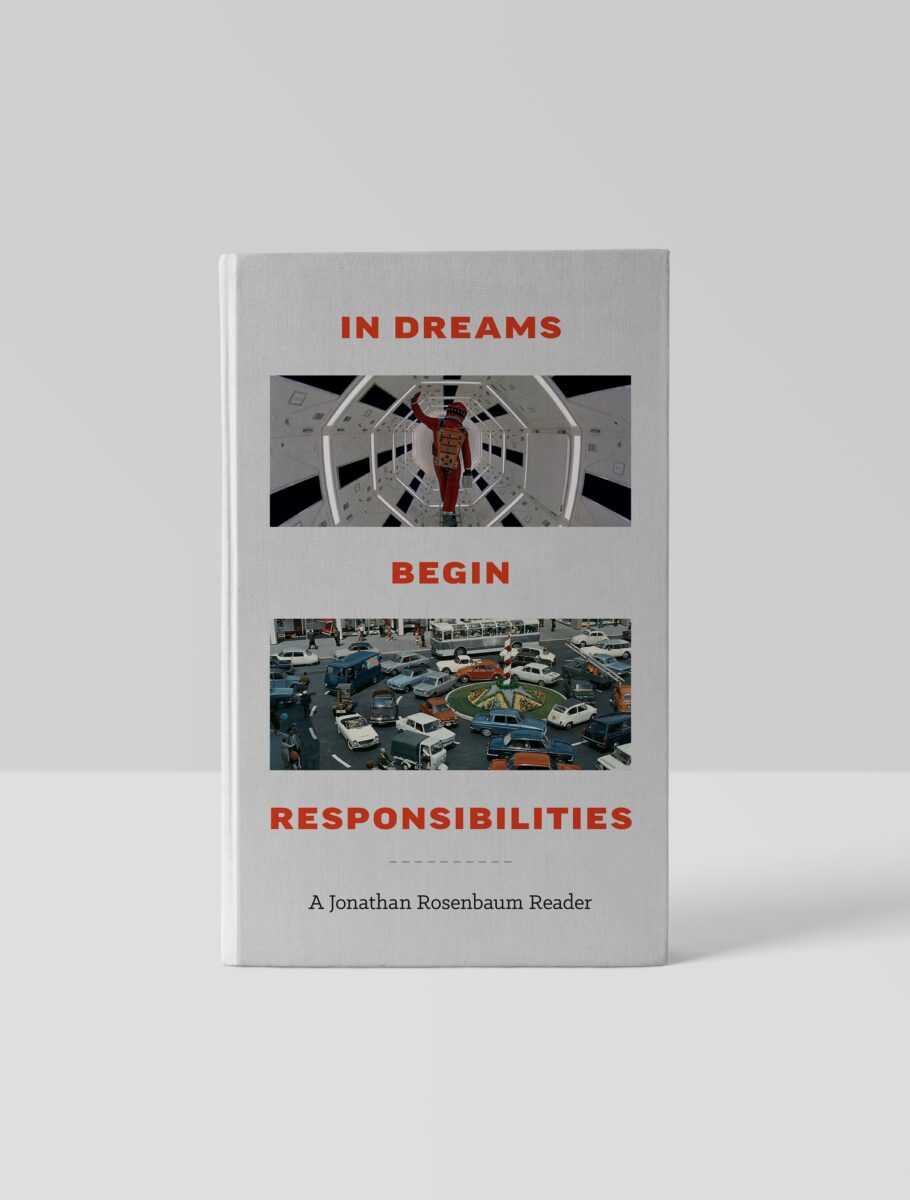

He has written multiple books on film. The latest, In Dreams Begin Responsibilities: A Jonathan Rosenbaum Reader, was published by Hat & Beard Press in June of last year, and can be considered the definitive culmination of Jonathan’s writing (to date!). An autobiographical and chronological journey, the book spans six decades of Jonathan’s writing about film, literature, and music (specifically jazz). Albeit chronological, the book ping-pongs between dozens of different subjects, ranging from Peanuts comics, William Faulkner’s Light in August, Jacques Tati, Spielberg’s A.I: Artificial Intelligence, Ahmad Jamal, Jean-Luc Godard, Phillip Roth, Mad, and roughly everything in-between, interactively connecting these separate threads and mediums into a personal manifesto of Art.

In celebration of the book, Metrograph hosted Rosenbaum for a double bill of two of his favorite films, WR: Mysteries of the Organism, and Giants and Toys, with post-screening conversations with filmmaker (and friend of Jonathan’s, through critic Manny Farber) Michael Almereyda.

I interviewed Rosenbaum at the Upper West Side apartment where he was staying, the day after David Lynch died and the day before his book signing. He had just finished downloading a torrent from the website Karagarga. He drank cranberry juice.

The Film Stage: Tell me about what compelled you to get this compilation together, which is an autobiography of sorts.

Jonathan Rosenbaum: I didn’t plan it as an autobiography; I wanted to organize my writing chronologically. And then I wanted to contextualize the pieces in the introductions, and then it turned into an autobiography. Also, ever since I wrote Moving Places, I tend to be autobiographical in my criticism. Because it’s really, largely, a form of political honesty. I mean, basically, it’s saying where my ideas kind of come from.

What do you mean by “political honesty”? I mean, I’ve always found there to be a political bent to your writing, so to speak. Even the title In Dreams Begin Responsibilities seems, to me, to be hinting at a leftist message. I know it’s taken from a W.B. Yeats play, but…

Well, it’s actually a little different. In 1914 Yeats had a book called Responsibilities. And on the title page he has two epigraphs, one of which says, “In Dreams Begin Responsibility.” And then it says under that “––Old Play.” So he’s quoting an old play. I don’t know what old play he was referring to or where he got that from, but that’s what the source is.

And why did you choose that as the title?

It’s just something that’s always appealed to me, and I’ve titled individual articles that. And I think it has something to do with the notion of freedom and the freedom of dreams, but at the same time doing something well––I guess you could say “socially aware”––with something that’s very personal.

In other words, I think an awful lot of my work is about––and I mention this somewhere in the book––this thing that appeals to me, partly about jazz: that it’s something that you, whether you’re playing it or listening to it, is something that is both an individual experience and a collective experience. And I think about movies similarly, in that even if you see something in a theater, you’re watching it with other people, but even if you see something at home on your laptop, it becomes social the minute you start discussing it. So I think that there’s a kind of way in which to combine things that are very personal with things that are very collective.

But I’m curious about the “responsibilities” part. I mean making a work of art, whether it be jazz or a piece of fiction or a film. You hold artists to a certain responsibility, in a sense?

Well, I think when you actually have a dream, there’s something that’s kind of amoral about it because you’re the only audience. But at the same time, when you want to make something out of the dream, that’s when you sort of enter society and you have responsibilities.

Right. I think even the cover reflects that idea.

Yeah. I actually designed the front and back cover myself, and I want it to be open-ended––which is the dream and which is the responsibility.

Right.

So in other words: I want it to be interactive. Not just me sort of determining what those words mean, but people using them, which connects with something that I probably repeat more than once in the book, which is a statement that Godard said to me in an interview once: “I’d like to be remembered as an airplane rather than as an airport.”

That word “interactive”––I think you were the one to properly describe Playtime as kind of, like, the first interactive film. So you extend that ethos to your own writing.

Well, I like to think that what I write is socially useful, but in a way that people can take my writing to other places. It doesn’t have to be my place, in other words.

Speaking about your place, I wanted to ask about a post on Twitter that went viral a couple months ago, where you posted your personal DVD collection on Craigslist.

That’s right.

Selling for $20,000.

That’s right. And I found a buyer the same day I posted it.

Oh, wow. I’m curious––first and foremost––why did you decide to sell?

Well, it’s a complicated story. I had been in a long conversation with the Film Studies Center at the University of Chicago––they were interested in buying my DVDs for a posthumous collection. The idea was that they would pay me the money now, but they would collect the DVDs after I died.

They had to do a kind of inventory first before they could do anything else and it took a while before they did that, and finally they commissioned a projectionist to actually go through and catalog it. But then after they did it, they found that they couldn’t get the money for it.

And so then I decided, “Okay. Well, I should still sell it.” And the guy I sold it to is a very successful pediatrician who’s a film buff in Chicago, and he has his own screening room. But on the last day of this month, we’re gonna start a film club where I pick the films, and then he orders pizza, and then we have discussions afterwards.

And now I’m considering selling all my books, which would double how much money I have. It would mean I could go to Paris on business class.

Oh, so you had never met this man before?

No. But we’ve, you know, we’ve had at least a meal together. We’ve had some conversations.

And does he have all the DVDs already in his house?

Yeah. He actually has them all shelved and everything. And, you know, there was a certain sense of loss to be shared, but at the same time it means less now because so much of the stuff you can get on the Internet for free. And so I’ve been loading up my hard drive ever since with several favorite things. I feel a certain lightness, you know, about having let go of it. Unfortunately, I have all these empty shelves now. I have to figure out what to do with those!

It’s interesting because, you know, there’s this kind of resurgence––or I feel there is––among younger film and music circles with physical media, so it’s interesting that you are letting it go. When you were giving it off to this pediatrician, were you hesitant to let go of any DVD in particular? Did you keep any?

Well, are there some that I even went and bought again since. The first film that’s gonna be shown in the film club is a film called The Story of Three Loves, which is an MGM episodic film from 1953. So I didn’t actually have the copy I had, so then I went and bought another one. And there are a few films like that that I have a particular love for and went and bought again.

The Story of Three Loves

Back to the book: you mix literary, jazz, and film criticism. I’m curious what compelled you to collect these different branches of your writing.

Well, I always felt bad that I hadn’t been able to reprint some of my book reviews because they’re important to me. Like the one I did for Gravity’s Rainbow, for example. So I thought about that and then I thought, “Well, there’s some jazz criticism I have”––which is less important to me, but at the same time I’ve been doing it––and then I thought, “Well, yeah, why not put them all together?” I didn’t know what I was gonna wind up with. I didn’t even originally think that I was gonna necessarily do it in chronological order. Gradually I became aware that, my entire life, I’ve been writing about jazz and literature and film. And I didn’t realize how much I’ve been comparing the art forms from the very beginning and how they’re all actually connected and important. So that was a kind of discovery I made while putting together the book.

It begins with a review of Dr. Strangelove that you wrote when you were at Bard College. I’m curious about those years at Bard in the early sixties.

I started college at NYU, actually.

Oh, okay.

1961. And then after 3 semesters, I was really missing, you know, being in a community. And I had a friend from a boarding school, a woman who was at Bard, who I went to visit, and she convinced me it was a great place, and so I transferred. And then immediately––even though I wasn’t a film critic then––I took over the Friday night film society. And, you know, sort of ran all of that. So I was still involved. But I was still learning. It was a great period for, you know, the new wave and all of that stuff, but I was still using the film society partly as a way of educating myself in some ways.

Right. Was there a vibrant film environment at Bard during the time?

Well, there was no film department. I showed Sunrise twice because the first time everybody was laughing and jeering and everything, and I got very upset because that was my favorite film then. And so I decided to program it again and try to see if I could prepare the audience for it differently. And it, you know, it wasn’t a total success the second time either, but it was a little bit better.

And what compelled you to start writing film criticism? Because I know that you actually were a fiction writer first.

That’s right. What happened was really strange. I went to graduate school partly for, well, draft-dodging, but also thinking then that I was going to be an academic. And then when I really got fed up with graduate school––and once I reached the age and realized that, for whatever reason, I wasn’t gonna get drafted––I could quit. I did. I did everything except the dissertation. And the reason why I didn’t do the dissertation was because I couldn’t find a professor who would do something on film and literature, and I couldn’t find a faculty member who would referee. So anyway: I quit, and a guy who I knew who was a friend of friends––actually a friend of my friend named John Bragan––he basically hired me to edit a collection of film criticism, which I did.

But then John became a Scientologist. And he disappeared with all of the stills from the book to work on L. Ron Hubbard’s ships.

Wow.

And so he became impossible to even contact. So anyway: in the course of putting together the book I met a lot of people for the first time, including Andrew Sarris, Manny Farber––at least on the phone. You know? So it’s kind of, like, I got involved. And I even wrote a piece for the book––one that’s never been published because it’s not very good, actually. But it was a piece about Sunrise, in fact.

And, you see, at that point I was then writing my third novel––none of my novels would be published––and at the same time I was in Paris and I found that I could be a Paris correspondent for Film Comment and I could write for Sight and Sound. So I was getting published as a film critic and not as a fiction writer. So that’s how I became a film critic.

And whatever happened to those unpublished novels?

Well, I still have copies of them. I could’ve put them on my website, but I don’t. There’s one chapter from the third novel that I put on my website.

So you knew you were a writer long before you knew you were a film critic?

That’s right.

And I guess that’s representative of this book itself, because it’s not limited to film criticism.

Right. And you see, I think there’s a kind of a French idea which I talk about: film is literature by other means. For example: the French magazine I wrote for the most, Traffic, is very much a literary magazine, because, I mean, it didn’t even have any stills except the tiny one on the cover. But in essence and style it felt like a literary magazine. And because I think it’s in France, it’s a literary culture.

And I’m curious about, you know, literary criticism and film criticism. Do you go about writing them in the same way?

Well, I don’t know. I don’t. It’s not quite the same because they’re different mediums, but I haven’t really analyzed it. I mean, I think each book review I’ve written and each film review, it’s almost like I feel like, ideally, I’m starting out from scratch. It’s not like I have a method that I use with everything and I applied it, or if I do I’m not aware of it. You know? It’s just trying to sort of deal with the challenges of a particular work.

Someone else who also saw film as literature by other means is the Chilean filmmaker Raúl Ruiz. You deserve credit for being one of the earliest champions of his work and familiarizing American audiences to him.

Oh, yeah. Most American audiences didn’t know who he was. One thing is that a friend of mine––who is a very good writer named Gilbert Adair––wrote two scripts with Ruiz, and what kind of amazed me was Ruiz’s originality; he didn’t care whether his films were good or not, or whether they were successful or not.

And I feel like it goes hand-in-hand with improvisation, which you talk a lot about in the book. The magic of a work of art is when, you know, someone has to come up with something they don’t even know.

Are you familiar with Karagarga?

Yeah.

I am actually downloading one of my favorites [of Ruiz’s], The Blind Owl. I love what Luc Moullet said about that film. It was something like, “I’ve seen it 5 times and each time, I understand it less.” And the thing is, [Ruiz] and I were friends, but I think, you know, we drifted apart and I think the two reasons we drifted apart was, one, he was kind of fed up with the fact that I kind of have a disability with language.

Even though I lived in Paris, I never became fluent in speaking French. And I think he was so good with languages. I think he was a little impatient. But I think the second reason we drifted apart was that he got more involved in big-budget movies, and that seemed, to me, going against the grain of his earlier work. I mean, when I did an interview with him he called it a capitulation in some ways.

The Blind Owl

Something I’ve noticed when reading the interviews you’ve done about this book is that you’ve had difficulty getting published by some presses because of its multi-media interest.

Yes. University of California and Columbia University Press. In both cases the editors liked it and the publicist rejected it. And the amazing thing––and what just took me completely by unawares––was that I had no idea that publicists were more powerful than editors. They don’t deserve to get government grants if they do, because they handled it really badly at California. They let me go on for four months thinking that they were gonna be doing the book, and then I got a letter saying, “Oh, by the way, we’re not gonna do it. We talked to the publicists and they will have too much difficulty with it.”

That’s terrible.

Yeah. So I didn’t even answer the letter; I was so angry. You know?

What is your relationship to publicists in general, and how do you view them––not just with this book, but over your career as a whole?

Oh, I don’t know. There are good publicists and bad publicists. I’ve been friends with some publicists. And others who I consider my enemy.

Right.

It’s something that I speculate a lot about in my recent writing, which is that: if you think about it, the intake that people have of language every day––whether it’s things that they read or things that they hear, the language that everybody encounters every day––98% of it is advertising. And because of that, 98% of the language they take in on a given day is lies and insincere lies.

It’s really about the market. That’s really what it is. In other words: the same thing with the idea of the Oscars. The whole idea of the Oscars is to resell things that have already been sold a second time. Again, it’s all about advertising.

What I’m talking about––a term that I use more and more often now because it applies to more and more things––is capitalist censorship. That’s why the University of California Press and Columbia University Press didn’t publish my book: it’s capitalist censorship.

And it’s concerning that we even see it in the academic presses.

The interesting thing about it––what’s so politically conservative about it––is that the economic model goes back to Reagan, which is that you take an existing market and you exhaust it. Nobody tolerates the idea of you creating a new market.

Do you think that extends itself to cinema as well? Like, this inability to imagine new ways of telling stories?

Well, yeah. And I mean, in terms of what’s made, one of the things that’s horrible about what’s happened to Hollywood is that the people who run the film industry are not film buffs; they don’t care. They’re just thinking about making money. And they have contempt for the audience. So in other words: they don’t even like the people they’re servicing. And, you know, they basically decided when I was growing up that films were for everybody. But they decided that everybody is a 10-year-old boy.

Would you describe yourself as a leftist?

Yes, and a universalist too. But at the same time, if I were asked, is there any national cinema that is better than all the others, I would pick the American.

I’ve heard that a lot of your writing’s done under the influence of marijuana. Is that true?

Yeah.

Do you still?

I stopped smoking everything. But I used to smoke liquid delta. A large part of Moving Places was written when I was stoned. If you are self-critical as a writer it just opens you up and liberates you a little bit.

Something you like to talk about is how you think critics don’t need to diagnose whether a certain movie is “good’ or “bad.”

The idea of the very notion of a film being good or bad implies good or bad independently of people watching it. So in other words: it’s a ridiculous concept because it’s ridiculous to assume that any film that’s good is good for everybody in the world, and vice-versa. I’m quoting myself here, but I think what a film critic should do is ask “good for what, good for whom?”

But I do think that there is something to say about how a critic does have a sense of authority. Right?

Well, I don’t know. Sometimes I proselytize for certain things and, you know, hope that the people who will like it will go see it. But I like the idea of interactivity; I like the idea of people. I don’t like the idea of somebody imitating me. See, one problem I had with Manny Farber when I replaced him as a teacher, he had a writer’s workshop and I found that everybody in the course was imitating him and he’s the worst person in the world to try to imitate. One Manny Farber is enough. Even though I want to influence people, I don’t like the idea of trying to breed people to imitate me; I like the idea of people going off in their own directions.

What is the role of a critic, then?

Critics should never have the first word or the last word. They should come in-between.

In Dreams Begin Responsibilities: A Jonathan Rosenbaum Reader is now available.