When you talk about John Sayles, do you talk about America? Watching and examining his beautiful tapestry of films, this reveals itself an easy question to ask and an easy question to answer. There may be no single filmmaker who has better captured the agony and ecstasy of the American experiment than Sayles. Yet his pictures never feel like homework. They’re funny, heartbreaking, and full of characters that are well-rounded and sharply drawn.

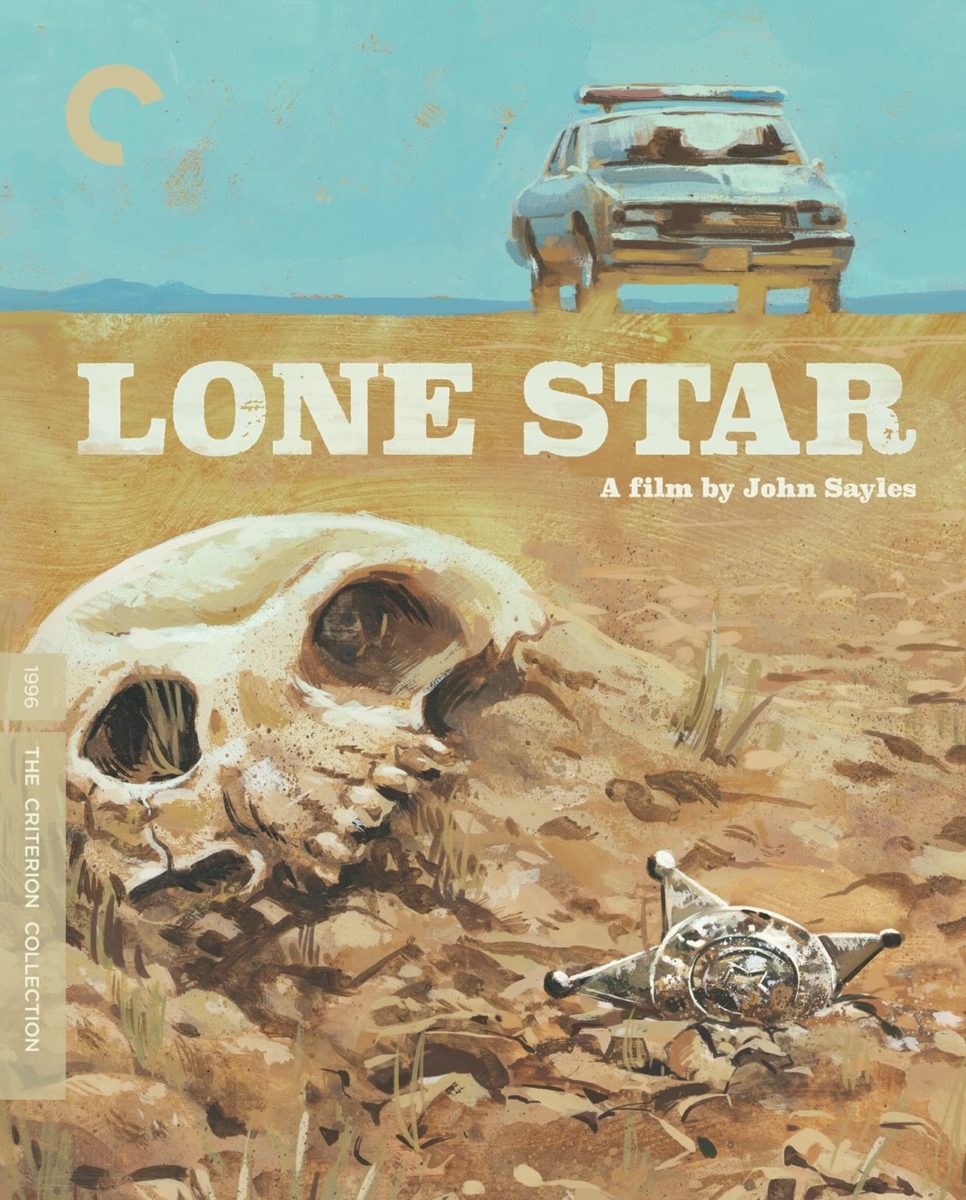

The Film Stage got the opportunity to speak with Sayles about his 1996 masterpiece Lone Star (now available on 4K and Blu-ray courtesy of the Criterion Collection), as well lesser-seen gems like Limbo, Go for Sisters, and Amigo.

Listen to an audio version of the interview below followed by a written version, edited for length and clarity.

The Film Stage: The reason we’re talking is because Lone Star, your great film from the mid-90s, is now a Criterion release on 4K and Blu-ray. It stands the test of time so well. You’ve made so many films, you’ve written so many films. With something like Lone Star, does legacy ever factor into your mind? Or do you just keep trying to tell new stories?

Yeah, you write books in my case and you make movies for them to be seen or read. To me, unless somebody is looking at them, they are just things. And then they come alive when anybody is looking at them. And that may be a home, that may be in a movie theater, or whatever. So what you hope is that your movies don’t disappear. I’m still seeing movies from the ’30s and ’40s I never saw before. And I go, “Jeez, that’s a good movie. How come I’ve never heard of that? How come it hasn’t been available for years and years and years?”

I was talking the other night with Ron Perlman and he was working with Guillermo del Toro––who has seen every movie in the world––but he hadn’t seen Nightmare Alley and they ended up watching it on a really crummy… somebody who stayed up late that night and taped it off of a TV. The original is really worth seeing.

Lone Star is probably the movie that got seen the most when it first came out because Castle Rock actually put some money into it––unlike most of our distributors, who just stuck it in the system and forgot about it. You want it to be available in some way, and if they are packaged in an interesting way it might be with a couple of other movies or with Criterion Collection, who do a nice job of vetting things. They’ve done things where, here’s seven movies with the same production designer. You actually say, “Wow! He was good. He worked in Europe and the United States.” It’s a nice way to bring people into a movie. Here’s movies with this actor in them, or whatever.

Right, on the Criterion Channel there are lots of great collections. Since we are The B-Side Podcast, I want to ask you, because one of our subjects a couple of years ago was Toshiro Mifune and it’s one of our favorite episodes. We tried to capture movies from his long career. We talked about The Challenge with him and Scott Glenn, and you have a writing credit on that. Do you have any memories of that movie?

Oh, yes. I was brought in to do a rewrite. I came out to Los Angeles and met with John Frankenheimer. I was a huge fan of John Frankenheimer’s and he had had a really rough patch. So he said to me, “Kid, I need this picture. I need a comeback picture to show people that I’m still kind of in the game.” And the mandate that I got was: “It’s Thursday. There’s a Directors Guild strike coming up on Monday. Scott Glenn has to say he’ll do it, and then they will green-light it, and Frankenheimer can get it made before the Directors Guild strike. So you have the weekend, basically, to get this thing. We have to get it to Scott. He has to say yes.”

No pressure.

The other part of it is: “The script we’re giving you, it’s okay, but it’s all Chinese people. And I worked with Toshiro Mifune in Grand Prix and I can get him to do this again. Make all the people Japanese instead of Chinese.” You know, the cultures and the martial arts are very, very different. Chinese martial arts are very circular and the Japanese martial arts are very forward and backwards. Luckily, I had read a lot about that stuff already just because I was interested. And he said, “Yeah, I can get Toshiro Mifune and can make them all Japanese.” And so I did a very intensive rewrite in three days. I was staying at a little strip hotel on the Sunset Strip, and I would literally call the desk and say, “Will you give me a wake up call in 45 minutes?” I would sleep for 45 minutes, and then I’d jump in the swimming pool and come back and write some more.

Then I handed it, I put it in the desk, and I said, “Call this number. I’m going to the airport. They’re going to come pick it up.” And I got home, and by the time I got home, Maggie said, “Well, two things: the Writers Guild strike, which was going to come before the directors strike, has been moved back a week, therefore Scott Glenn just said yes. John Frankenheimer wants you to come to Tokyo and do a polish on the draft.” I went there. And then mostly John was casting local people upstairs and he’d give me notes on the 20 pages I sent off to him. I’m a fast writer so that wasn’t the problem. He did say, “You know, Toshiro is a little sensitive about the fact that he can’t say his Rs or Ls. So can you take all the Rs and Ls out of his dialogue?”

Behind the scenes of The Challenge

And there’s a scene where Scott Glenn––who is very left-handed, and there are no left-handed samurai if you watch samurai movies. They let barely any boys be left-handed until they started losing the Little League World Series to left-handed pitchers because they’d never faced one. And so I had written a scene where Toshiro came in and just said, “You can’t use your left hand.” But, you know, he can’t say the L or “that’s wrong.” Well, wrong is an R sound, so finally in the movie he comes in and he looks at him for a minute and he goes, “You stink!” No Rs or Ls.

So that was a lot of fun. I did the rewrite, then I had to go home because the Writers Guild strike did start. Frankenheimer really did quite a good job. The stunt coordinator, Steven Seagal in those days, did a really good job too. I got to go to Kyoto with Frankenheimer and see that kind of cement pagoda convention building the final fights are in. And John Frankenheimer does very good action if you think of Black Sunday or some of those things. And Seagal did a very good job of half-samurai, half-modern weapons kind of battle royale. So it was a great experience. It’s always nice when you only work four days and the movie was made and you get a credit. [Laughs]

It’s interesting because this has come up a bit recently. We spoke with Carl Franklin last year, because One False Move was coming out on Criterion. I know you worked a bit with Roger Corman. He worked a little later than you on a Corman picture. Is there one major thing you learned from Roger?

You learned it every day, which was: there are problems you can solve with creativity and hard work, and then there’s those things you just have to throw money at. And those are the things that you don’t find in a Roger Corman picture. Roger would basically okay a script because he paid $10,000 to have it written and he got three drafts out of that, and he and Francis Dole, his assistant, would have very good notes, very specific notes. He wasn’t going to rewrite a whole lot or hire new writers. And then he handed it to a director and said, “Here’s your budget, here’s your time, make the best movie you can make, but you’re not getting any more money and you’re not getting any more time.”

There might be three action sequences or frontal nudity in one scene. As long as those were in there, he knew he had a good trailer. He wasn’t review-dependent. They were genre movies. So he got to know, “Okay, this will fit in the spot.” And every once in a while, as in the case of Piranha, something would have legs––or fins, in that case––and it would stay in the theaters for another two or three weeks.

Piranha, right. Because for those who don’t know, you wrote Piranha. You have such an amazing career in that you start as a novelist, Union Dues, and then you started writing these screenplays––which for those who know you as a filmmaker, they’re not John Sayles movies, right?

Yeah.

You do that work to fund the other work in a lot of respects, right?

Yeah. And you kind of think, “Okay, what are the genre movies that I love?”

As a director, is there a genre you’ve always been itching to try?

I’ve been trying to make a Western for about five years and we’re still trying to cast it and get some money based on the cast. That’s always a genre I wanted to do. One of my favorite movies of this year is Godzilla Minus One.

Yeah, it’s a great movie.

That’s a really good movie. And I’ve seen a bunch of Godzilla movies and it’s one of the best, easily, and it actually helps to know a little about contemporary Japanese politics and culture to appreciate. We’re going to use a Godzilla movie, but we’re going to talk about some shit that went down. What was that stuff with the tsunami? And the reactor that might actually kill us all and the government not really telling us that? So I had certainly seen a lot of those genre movies, creature features––especially on TV or in movies––so I had an appreciation for them.

Speaking of Guillermo, you helped on Mimic.

Yeah, which was a lot of fun working with him. But I’ve always felt like, with horror movies or whatever, it’s not like there was a shortage of horror movies or people who could direct them. So if I’m going to do the work––and in many cases invest my own money in something––I’m going to make something that nobody else is going to make. Even if it is within a genre, in some ways it’s not going to be what you usually think of a cookie-cutter genre movie.

Well, that’s a good segue. We wanted to shout out a few movies that you could call B-Sides. Limbo with David Strathairn. What a film. I would just encourage everybody to seek it out. That was one of the few films of yours that I had not seen and in prepping for this I watched it and was blown away by. You’ve said location comes before your writing usually. How do you even location-scout a movie like that?

Well, we got invited to go up to Alaska and do kind of a seminar thing. And part of that, they said, “Well, we’ll pay for your ticket. We can’t pay you. But we have all these people. We’re going to take you out and do fun things.” And so we got a real feel for at least the Juneau area. So we went to go fishing with people and go on a glacier and see a salmon run and those kinds of things. And I was just struck: here’s a place in America where you are reminded––even in the capital city where there is only 40 miles of road––that nature is big and people are small. And how does that affect you? And unlike most movies that are set in Alaska, we shot in Alaska. So when we went back up to scout, we already knew a bunch of people and things that we had seen just as tourists.

Basically, I had already said there’s going to be a scene there. So many people we know in the Juneau area worked on the slime line. They cut the heads off fish and they gutted them. They have all the stuff on and they hose it down at the end of the night. That’s part of life here. “I’m going to have a scene on the slime line. We’re going to cast local people who have been on the slime line so they know how to do it. They’re not going to be going, ‘Yuck.’ I’m holding fish guts while I’m acting here.” So there’s that.

Limbo

A couple of my movies… I know with Sunshine State, I went down thinking I was scouting for one movie based on a short story that I had written. I went down to the Redneck Riviera on the west coast of Florida, the Gulf. And it just wasn’t there. The place that I had grown up seeing and I’d hitchhiked through a bunch of times, it had changed. It had turned from mom-and-pop tourism to corporate tourism. And I started thinking about the difference between those. And then I went to Amelia Island, because there was this historically Black beach there. And all of a sudden I realized, “The Spanish came here and built me a fort. We could just wander in and shoot.” And it was used by the Civil War people.

So sometimes you’re scouting before you even write it and you find… something like Passion Fish is a good example. That house that we shot in for Passion Fish belonged to a musician friend of ours who said, “No, you got to stay at the camp tonight. My parents own it.” And we woke up and there was this Spanish moss hanging down and there was the bayou. And Maggie said to me, “You know, that movie about the woman in the wheelchair and the woman who takes care of her, this is where it should happen.” And I said, “Absolutely.” So there’s a certain amount of serendipity, but I also feel like location gives a feel to the movie. That’s one reason that we try to shoot in, if not the exact place that it happened in, a very similar place. So Matewan, we didn’t shoot literally in Matewan. It was too hard to get to, for one thing. But we shot it in a town that looked a lot like it.

It’s so fascinating because it doesn’t really get talked about enough, how important location is. It’s kind of one of those things you just assume. It’s an unsung hero in a lot of your movies because I feel like the appeal of basically all your movies is their naturalistic, humanistic quality. They feel really lived-in, and a lot of that has to do with the way you write your characters, but it’s also the locations they occupy. It feels like you just showed up with a camera.

Right. I think I’ve written five movies set in Chicago and one set in Detroit, and none of them were shot in either of those two cities––shot in Toronto or Montreal or somebody’s studio. And you lose something; you lose some specificity.

Yes, 100%. Another movie we wanted to ask about is Amigo, which is now from fourteen years ago and comes from part of your novel A Moment in the Sun, right?

Yeah.

I’ve been reading Yellow Earth and I have to ask: there’s a character named Hardacre in Yellow Earth. Is that Hardacre related to Chris Cooper in Amigo?

Yeah, he’s probably a descendant. [Laughs] But they are not the same guy. It was different times. It’s a good name for both of them.

When I was reading Yellow Earth, I was thinking this might be the same lineage.

That was an interesting movie in that, as I got to know more about the Philippine-American War, one thing that struck me was: we won that war, but we don’t celebrate it. How come? And then as you look into it, you realize, well, this is where we learned how to waterboard. There was a heavy antiwar movement, which was rare in the United States at that time, and the two letterhead kind of people––the most famous people that led it––were Mark Twain. Because he thought Americans shouldn’t be imperialists; they shouldn’t be taking over other people’s country. He thought it was really just kind of, “This is terrible. This is not what Americans do.” And Mrs. Jefferson Davis, who was worried about white boys going over there and burying those brown girls. Miscegenation. So she was really against that war.

A really weird Venn Diagram.

Yeah, well, there were a couple of times when they were on the stage together––kind of like Timothy Leary and Howard Hunt, one of those Watergate things. What I discovered was that before that I only found two American movies made about the Philippine-American War. One is called The Real Glory. And it’s basically Gunga Din recycled to another war. I think David Niven is in it and Broderick Crawford and Gary Cooper. And the evil Datu, the Philippine bad guy, is played by a guy who was in the Moscow art theater [Vladimir Sokoloff], who does a very good job. And then there was another one called The Day of the Trumpet [also known as Cavalry Command] with John Agar, which is a pretty awful movie. I said, “There’s two movies?” That was a significant war in its time. This is history that isn’t forgotten. It was buried on purpose.

Yeah, back when that was something you could do.

Yeah. So I just thought, “Well, that’s interesting.” And then through Mario Ontal––who had been an assistant editor that I’d worked with, who’s Filipino––I got to know Joel Torre who is like their Tom Hanks. They have a real film industry, but I realized we could make a movie for half of what we could make in the States. And if I make it on a village level, not a war level, I could make a movie there for $1 million. And I think we have $1 million in the bank.

Amigo

You went out there and did it.

We went out there and did it and got to work with a wonderful, wonderful Filipino crew and cast. At that point they weren’t shooting sync sound for their movies––like they used to not do in Italy. And so they said, “Well, bring your own sound people, and then they could teach some of our people how to do it.”

Oh, that’s cool. Do they do sync sound now, do you know?

In a couple movies they have, but generally they’re just too much in a hurry to. But also, it’s a country with maybe 15 or 16 languages. So Joel started, he’s from Negros and Tagalog was his second language, and he insisted––you know, popular young actor––“I’m going to do my own looping.” And he would notice that the technicians were turning their backs because they were laughing at his accent. So he did like a year or two of really intensive work.

So now just Tagalog sounds like he was, you know, born in Manila or whatever, right? So it’s, you know, all those countries, you know. I acted in one of the first sync-sound Italian movies called La fine della notte a long, long, long, long time ago. And, you know, it was, like, a big deal. People were talking while we were shooting, and one of them was the producer taking phone calls. And the director’s saying, “We’re shooting sound!” “Oh, right! Shit!”

So we’re coming to the end of our time, but I want to just shout-out Go for Sisters, an incredible film from a few years back. I encourage everybody to seek that out. Some incredible performances in that film. I mean, really to our earlier point: the location is so crucial, and it has that border element that Lone Star has in a different way.

That was also a good example of me writing a movie where I kind of thought, “Well, there’s not that many movies about female friendship.” And a lot of young women who, you know, they could “go for sisters” there. That happens when you’re growing apart. But I wrote the movie, and then there were these three actors. And I said, “Oh, I could get Eddie Olmos to do this,” you know, and I could. And then, you know, “The two women, I think they’re going to be African-American. I got to do a rewrite, you know, and work that in.” So, you know, it was one of those things where, God, we had four weeks to shoot it. We had 62 locations in two countries. We had a little less than $1,000,000, but everybody was really into it. And it’s a road movie so, you know, you’re moving locations.

Traveling circus.

Just knowing that I had those three actors at the center of it, I got a movie done.

Is there any B-Side of yours––book, script, or movie you wrote––that you want to tell everybody “seek this out?”

Boy, I’m trying to think of what doesn’t ever get seen. You know, actually the B-Sides are all the movies I wrote for other people that should’ve got made and didn’t. There’s about 14 of them that, boy, I wish somebody would make. You know, my last two novels, Jamie MacGillivray was a screenplay first that I wrote for Robert Carlyle and then, 20 years later, we couldn’t raise the money. And then I have a book coming out next year called To Save the Man, which is set in the Carlisle Indian School in 1890, and that was a screenplay. So one of the things that happens if you’re a novelist and you can’t raise money to make movies, you say: ”Jeez, can I write that as a novel?”

Yeah. “I just want to know the story!”

Exactly!

Lone Star is now available on The Criterion Collection.