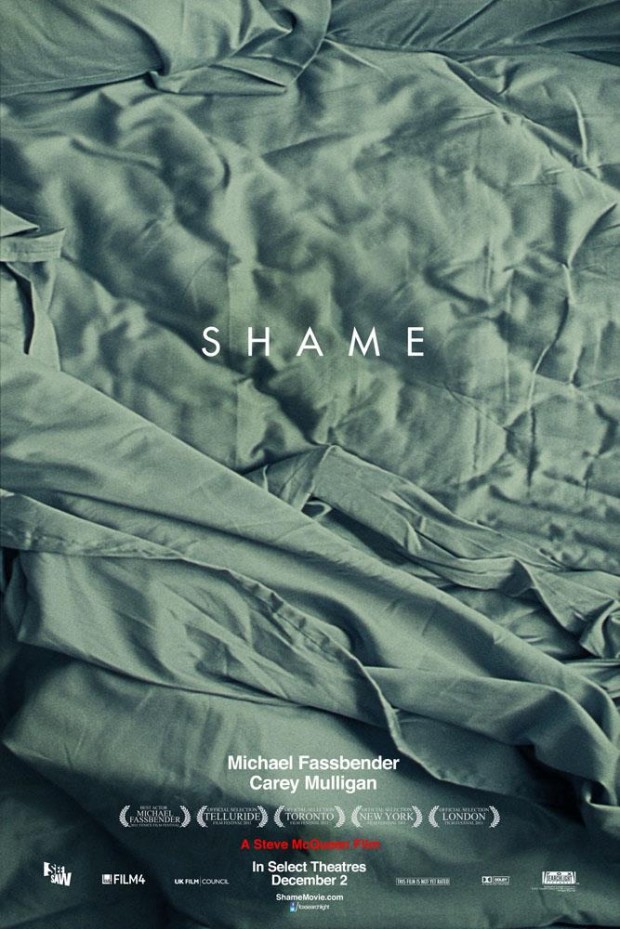

British artist Steve McQueen made one of the past decade’s most impressive filmmaking debuts with Hunger, a drama focusing on the 1981 hunger strike conducted by IRA member Bobby Sands. That affecting, sometimes disturbing experience helped put him on the world cinema map, and he’s returned this year (along with Hunger star Michael Fassbender) for the sex addiction film Shame.

We were lucky enough to sit down one-on-one with the director, where he talked about – among other things – unintended connections between his two features, his source for portraying humanity in a realistic fashion, and injecting humor into a film about a sex addict.

I want to start this interview by connecting it to your previous film. I feel as though there are certain thematic similarities between Hunger and Shame. Do you feel that any are present? Specifically, in the conflicts that the lead of either film endures?

Well, I think — interestingly enough with Hunger — it’s about Bobby Sands, who was in prison, in a maximum security prison. This guy in this extraordinarily secure, sort of formal, imprisoned state — but within that, in order to create his own freedom, he stops eating. On the opposite side of that, of course, you have Brandon, who’s living in this metropolis, being Manhattan. And within that, the whole idea of western freedoms. And he’s an attractive man, he has a good job, he has quite a good salary, my goodness — but within that he imprisons himself through his acts of sex. So, somehow they’re polar opposites, but they’re very much connected.

Was that an intentional decision? Are there certain ideas that you just go back to?

No, it was an absolute coincidence. I mean, of course, what’s the furthest thing you can think of from Bobby Sands, who’s dying of a hunger strike? A guy who’s a sex addict. But, somehow, I think they’re connected.

Throughout the film, I felt a lot of sympathy for Brandon; I think he’s a very sad character.

Yeah, absolutely.

So, do you also view him as sympathetic?

Oh, absolutely. I think Brandon is extraordinarily sympathetic, because he’s one of us; he’s not a freak. He’s one of us, and he’s trying. Yes, he has this addiction, but what made me want to make a film about sexual addiction is something like alcohol addiction. Because alcohol addiction, you know, it’s somehow, “Oh, it’s alcohol addiction. I’m not going to do that; I just won’t drink any alcohol.” Or do any drugs, or heroin, or coke, or whatever. But this has to do with sex, which all of us participate in; it’s much more closer to our own reality.

When crafting the script with your co-writer, Abi Morgan, were you very much trying to make him sympathetic?

Yes. And there wasn’t even a “trying.” It wasn’t even necessarily a huge effort, just because this person is an addict. You know, we’re all trying to get through this world the best way we can, and, of course, he is this person who’s trying to do the best he can, too. And he’s one of us — like I said, he’s not a freak. It’s an interesting question, because people have no real sympathy right now for people who have sexual addiction. And I think that has to do with our own relationship to sex; it reminds me of the early ’80s when people were dying of AIDS or HIV, and people do not want to deal with these people at all.

Even though you’re obviously dealing with very serious subject material – and I think it’s a resoundingly sad film — I also found a lot of moments to be quite funny. Were you and Morgan looking to inject humor, so as to not make it a completely dour experience? And, if so, how did you integrate that into the screenplay without feeling tonally inconsistent?

How we did that was just by sort of being very observant of New York. I mean, similar to, you know, the David character [James Badge Dale] — I think he’s great. He’s this fast-talking guy who’s a bit of a horrible guy — and he’s the boss — but he’s kind of entertaining to be around. You know that person, of course.

The other example could be the dinner between Marianne [Nicole Beharie] and Brandon — and the waiter. That was an experience I kept on having in New York. Trying to eat a meal and, you know, every four seconds you’ve got this guy popping up at your table trying to get into a conversation. So that was one of the things I tried to put in.

What did you look toward when trying to capture moments of reality and authenticity? Was there any particular inspiration, other than just the city of New York itself?

Good question. [Pause] I’m just desperate to see cinema in a way that I see the world. Not that I… yes, I am. Because I didn’t want to make a movie about reality; I wanted to make a real reality. Hence the whole idea of, you know, people talking about “backstory,” or Brandon not saying much — because we don’t say much. Most of the time we have a conversation with people, we talk, in a day, we talk about this shit. It’s just to get by, to kill time. Most of the time we tell little lies and stuff, but we don’t really talk about what we actually feel. We don’t actually open up to people and say, “Oh, this is how I feel, this is where I come from.” It never actually happens. But in movies, it happens all the time; I just wanted to make a film where that wasn’t on the table. Where you can actually look at a film within our own reality.

I think it’s interesting how, in your work, there’s not much in the way of exposition. I feel like you’re very much thrown into the world as events are already underway. Do you prefer this method?

I like the idea of that, in some way — well, I like the idea of the movie’s been playing way before you enter the cinema. So when you sit down and see Brandon on the bed, you happen to be there at that time. When Brandon is on the train, you leave the cinema at that time, the movie just goes on — the movie just goes on. So, I like that. Yes, you can say that.

But another difference between Shame and Hunger is language. I mean, within the IRA, a situation happened where violence was pushed to an absolute extreme. I think what happens then is, after that, people push language to its absolute extreme; that’s what Bobby Sands was doing. Talking to get some kind of truth. You know, using language, and pushing it, and challenging it as much as he can — for example, with the priest.

But, on the flip-side of that, you get Brandon, who hardly says a bloody word. I think that’s particularly indicative of us today. When we talk, it’s not — it’s like the conversation between David and Brandon in the office. The conversation is about something completely different to what they’re actually talking about. And that happens often in a day.

Did the process between Michael and yourself change greatly the second time around? If so, how?

It was quicker, because we knew each other by then. And we trusted each other. Of course, we trusted each other on Hunger, but that was the great thing about Hunger, it was the start of a beautiful relationship, in that kind of a way. It’s like falling in love: You don’t know when it’s going to happen, it happens and it’s kind of like, ‘Wow, let’s maintain this. Let’s get on with it.’ And I think what happens in some ways, with this situation, it’s just one of those things where… it just got faster. Now we grunt and groan. Sometimes I, you know — there was a take, and it’s not exactly what I wanted, and I walk up to him. And before I get to him, he goes, ‘Yeah, yeah, I know.’

So you must prefer that, right? To work quicker?

Well, I never knew. Again, my naivete is kind of interesting, as a first-time director; I thought all actors were like that! [Laughs] But, no, they’re not, of course. But that’s also good, because then working with Carey Mulligan, and Nicole Beharie and James Badge Dale, you challenge them. And if they’re good actors, they get it. They go for it, and there’s a reward for them, as well, which is just extraordinarily exciting.

How did you get your actors to be comfortable with one another onscreen? I feel as if you’re lucky to get actors who are so brave, because there are a lot of moments that many wouldn’t be willing to do. So how do you get them ready for a sequence where there’s something particularly harrowing?

I don’t know if it was ‘harrowing’; again, they’re actors. With nudity — people talk about that, for example – I mean, if you’re not going to do that, it’s like a dancer: Are you only going to dance on your left foot? I mean, you know, you’re an actor. And that’s it. You’re there to portray humanity, and I think it’s about preparing — talking, rehearsal and getting to know an actor, getting them to trust you. But I don’t hire actors; I work with them. So, hopefully, the actor can become a sphere, so whatever they do, however they roll, it’s perfect. You want to build them up to that sphere, so whatever they do in a situation is exactly how they would do it. Because rehearsals can do that, too. But research and talking and talking and talking. And getting them to trust you.

When you seek an actor, is trust your main priority?

It has to be, because they’re putting themselves into a situation where it’s often possible to get hurt. As far as this film is concerned, absolutely. There was a possibility of getting really hurt, you know? And, therefore, you have a responsibility of being with your actor and working with them.

I know that next you’re working on 12 Years a Slave. What stage of development are you currently in on that film?

I think next year we go and do some sort of thing. The script is done, so that’s great and we’re in kind of an advanced stage – but I just need time off. I think I need a couple of months off, and there’s also a museum show happening this year, as well; I just need some time off. Just to sort of, you know, get myself together. Because, you know, you have to look after yourself when you’re making films, because it can be kind of — again, I threw myself at Hunger.

I mean, when I finished Hunger — all the press and stuff — I had this huge rash under my arms. And it was just because, when you’re talking to people who have murdered people, done horrible things to people, you can carry that with you, or put your blinkers on and focus on the film and channel that stuff to the film. It’s kind of, you know… shattering. So I don’t know what’s going to happen to me after Shame. I just hope I can have the chance to sort of lay low and come back up again.

Shame opens in limited release on December 2nd.