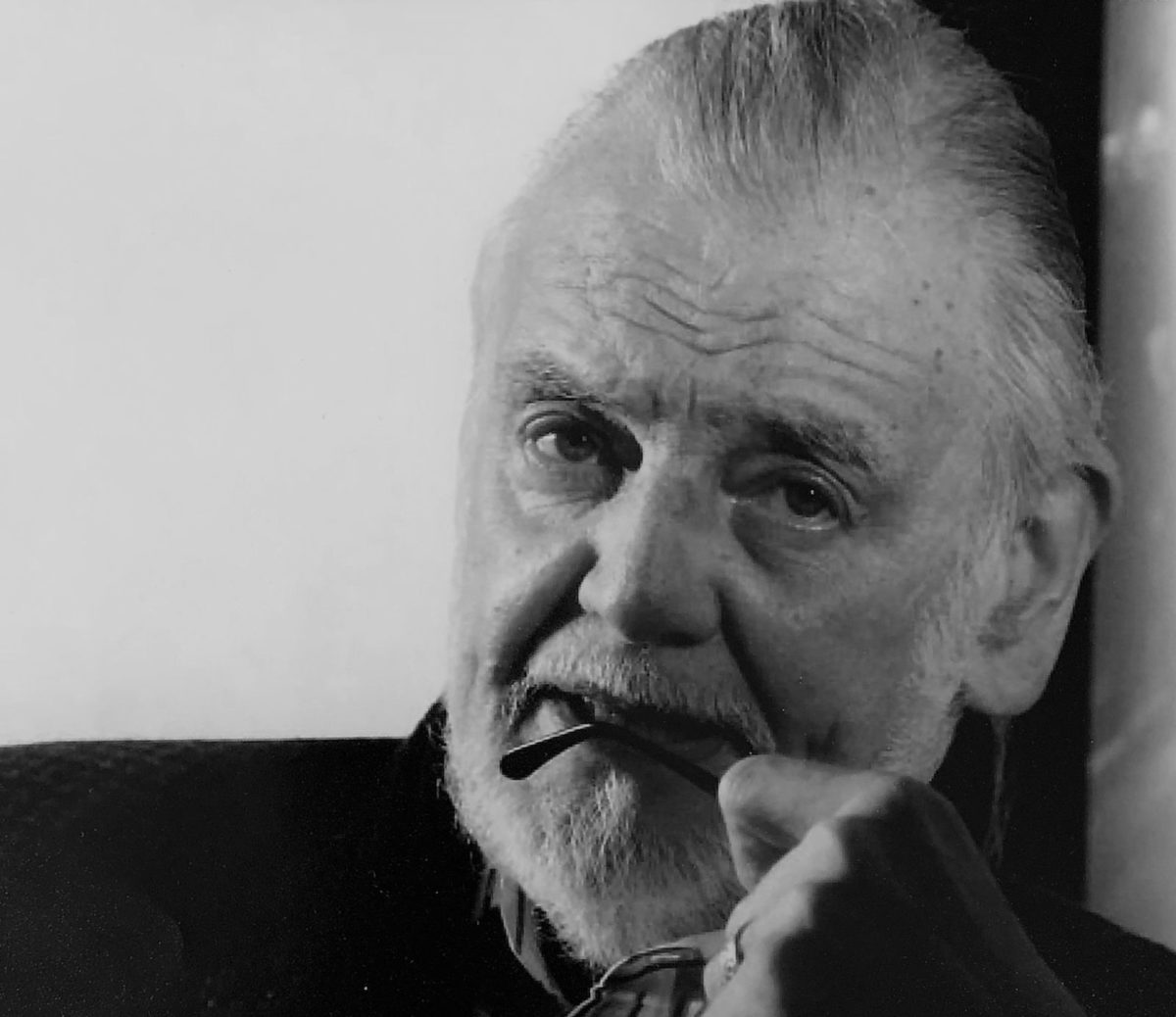

Suzanne Desrocher was tending bar in Toronto when she noticed that the tall guy with white hair was becoming a regular. “I had spied him and thought he was some kind of an artist.” She didn’t know who he was at first. An ex-boyfriend finally made a proper introduction one night. His name was George A. Romero and he was in town making the movie Land of the Dead, then in post-production. Did Suzanne wanna come over and watch it? “I was a bit nervous about it. I’d heard he was a zombie director and that wasn’t my kind of thing, I thought it was gonna be trash. I wanted to polite,” she said with a laugh. “He shut the TV off and said, ‘What did you think?’” I told him, ‘It’s not that bad!’ He roared with laughter. I couldn’t have reviewed the film better.” Romero made it clear that he wanted to be a bigger part of her life but to Desrocher he was a walking red flag. “Oh no, no, no, that can’t happen. That’s craziness. He was older than me, he was married, he was a smoker. It was a non-starter. But he said, ‘Listen, let’s just have dinner.’ And I did and I had fun. The second time we got together it was another great evening and I just never looked back. I wasn’t a horror fan but we had everything in common. He changed my life. He asked me to take a chance on him and I did and I married him five years later.”

As you might imagine, part of the way in which the Bronx-born genre master changed her life (beyond the addition of Romero to her surname) is that Suzanne Desrocher-Romero is now doing press on his behalf. Before passing away in 2017, Romero made a shocking confession: he’d made a movie in 1973 that almost nobody had seen. Speaking to his widow ahead of The Amusement Park’s Shudder premiere, she said, “I was gobsmacked, basically. I had never heard him mention it and then when I saw it, it was edgy, disturbing, and relevant––all of those things. ‘Why did you never mention it?!’ He said, ‘It was nothing, a three-day shoot, bing bang boom. I directed it but I was a gun for hire,’ the only time he ever just got paid to do a job. It was never ‘a film,’ but an industrial meant to play in community centers. It was never meant to be a film.” With Suzanne Desrocher-Romero creating the George A. Romero Foundation after his death, also overseen by Romero’s daughter Tina and collaborators Dario Argento, Greg Nicotero, and John Harrison, among others, they had a mission. “Now this is going be our first task, getting this restored,” said Desrocher-Romero. “Let’s see if people have any interest in seeing this film. It’s been astounding––incredible, really. I’m not sure why, but it has impressed people and I’m glad of it.”

That movie, The Amusement Park, is one of the most exciting film restoration events of the last few years, an incredible addition to Romero’s filmography and broader legacy. It’s a PSA about ageism, but perhaps more specifically about the way society has been structured to ensure some people feel deliberately left out and alienated. It concerns an old man (Lincoln Maazel, later of Romero’s florid working-class vampire movie Martin) who experiences a horrifying day at an amusement park where every interaction carries with it no small degree of menace and ends with him a little worse off than when it began. By the end he’s a sobbing, broken wreck, having seen some of the most terrifying and upsetting things civilization has to offer. He’s chastised for both his age and relative poverty. Romero was asked to make this movie by a Pittsburgh-based religious group called Lutheran Services; though they gave him a free hand knowing he’d directed Night of the Living Dead, they were so shaken by the finished product that it never officially saw the light of day. After a few screenings for friends—e.g. the great horror writer Daniel Kraus, who worked with Romero on the book The Living Dead––it appeared in Dave Kehr’s MoMA restoration festival To Save and Project just before the pandemic hit. The response, as Desrocher-Romero points out, has been overwhelming. This is a major new work, one that feels brand-new despite being (and truly looking) over 40 years old, and hits with the impact of a Louisville slugger.

The Amusement Park may shock even fans of Romero’s work, operating as it does by a set of narrative rules uncommon to his political horror cinema. “George as an artist felt very boxed in, put in this box as a ‘zombie director,’ and part of what I do is to see if we can unbox him. We’ve got unpublished work at the archive which was very important to me because I wanted to make sure his work was protected, curated, and studied. It’s very important to me that scholars have access to him, to his work. It’s multi-pronged. It’s about elevating horror, the genre, supporting filmmakers, genre filmmakers, independent filmmakers, supporting women in horror, putting cameras in young people’s hands. We’re young, we’re three-and-a-half years, and inch-by-inch finding our lane. I’m extremely pleased with our symbiotic relationship with the University of Pittsburgh, the horror studies center. People have been writing [horror] since the beginning of time. The Greeks, the Gothics. I’m learning! I actually know more about George’s career now than I did when I was married to him, I have to say. The learning curve is big! You know that expression, ‘This isn’t my first rodeo?’ Well, this is my first rodeo. It’s a labor of love done with a pure heart. There wasn’t a depositor for work like this and now there is. It’s all about protection.” One can now go to the University of Pittsburgh’s Romero wing to read his old scripts and view old artifacts from his life and movies. It’s not every horror director who gets this kind of treatment, Desrocher-Romero points out, and she’s proud to have opened the floodgates.

The Amusement Park‘s first screening made clear it needed serious help; Sandra Schulberg and IndieCollect stepped in to help bring it back to life. “It was warped. It was scratched, faded, magenta, all of it. Frame by frame, they did the best they could. I would be called in to look at the process. They worked on sound and everything. I oversaw it but Sandra and her team at IndieCollect were brilliant. Lovely people. And of course it’s right up my alley. They want to protect and preserve and cherish old films!”

It was being with Romero that brought out her love of classic films. “He was a man who loved life, loved to laugh, and loved to watch movies. He thought I was deprived. He spent 12 years educating me. We would get the TCM monthly program and he’d highlight all the films I needed to see. I have to say, with pride, that toward the end there weren’t too many highlighted films. My professor was proud I got to see these movies.”

I mention how much Romero spoke about his love for Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, specifically their 1951 film The Tales of Hoffmann, and how it struck me that The Amusement Park was the closest he got to emulating their style. “He loved them. You know when he saw Tales of Hoffmann… for the first time he saw how [films were really made]. How Powell managed it. The art, the craft, and he said ‘I can do that. I think I can do that.’ Somebody was asking me, “Do you think The Amusement Park is a stepping stone?’ I think he learned from every movie he did. For him it was very important that he become a solid filmmaker. He studied other directors and took from them. He actually never thought he had a style, but boy does he ever have a style.”

Speaking to the filmmaker’s self-deprecating nature, she said, “It’s funny because, well… not so funny. When he was diagnosed with cancer, he said to me ‘Suze, I don’t wanna talk about business.’ I said ‘Okay, no problem.’ But we were game players, and one night we were playing Scrabble and I very casually asked him what he thought his legacy was and he said, ‘Nobody really cares.’ Okay, wow… that kinda shocked and upset me. He passed away and I kept hearing those words. Kept hearing them. I thought, ‘Jesus that’s not true, I know it’s not true.’ I know those words gave me enough momentum to say, ‘Okay, I’m gonna see what I can do.’ We created the foundation and my job, Scout, is to prove him wrong.”

When she talks about Romero, his work, and their life together, there’s the faintest break in her voice, and it catches; I find myself getting emotional too as she holds up her hand for me to see something. “I still wear my wedding ring because I’m very much in love with my husband.”

The Amusement Park is now streaming on Shudder.