I didn’t know who Richard Ayoade was until 2010 and I quickly learned it was the perfect time to find out. My introduction was courtesy of the brilliant British television show The IT Crowd and his fantastically drawn Maurice Moss. I mainlined the first three series and eagerly awaited the fourth only to see co-star Chris O’Dowd journey to mainstream acclaim with Bridesmaids less than a year later. When would Ayoade’s turn come?

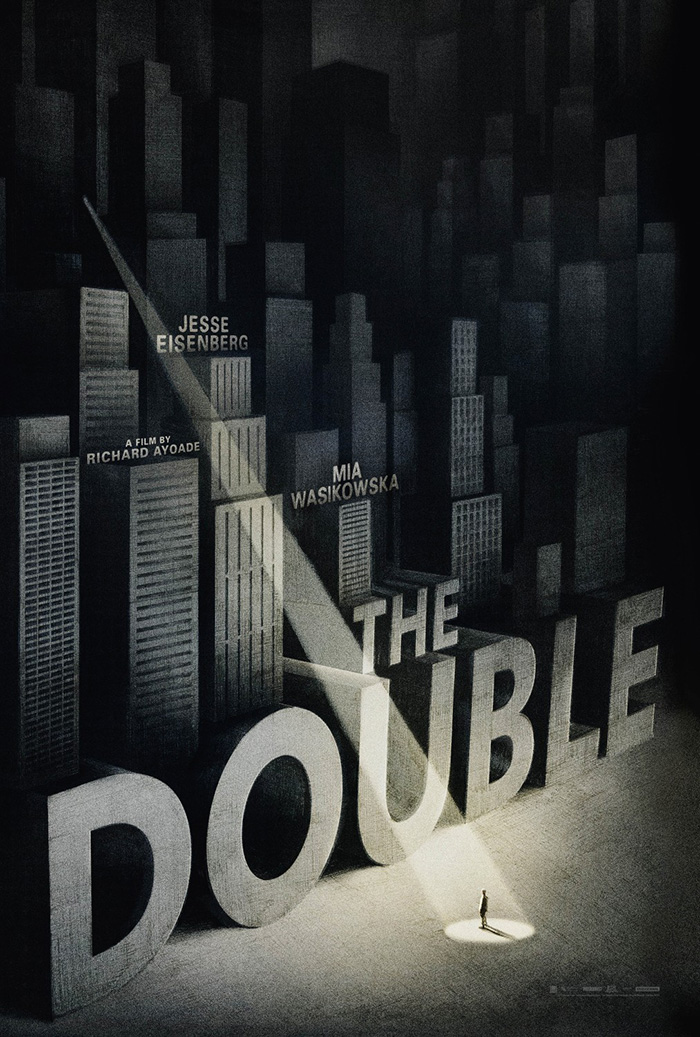

Well, it wouldn’t be the much-maligned The Watch—we can all agree on that. No, the comedian found that his path to America’s consciousness would be behind the camera, achieving praise for his directorial debut Submarine in 2011. His name quickly became commonplace with cinephiles as one to watch and a sophomore effort entitled The Double dropped at TIFF 2013. A more stylistic endeavor that retained the brilliantly dry comedy we’ve come to expect from the artist, this Jesse Eisenberg-led film earned lofty comparisons and a moderately divisive reaction.

Eight months later and it’s finally time for The Double to hit theaters stateside. And as Ayoade joked on Late Night with Seth Myers, it isn’t necessarily the most palatable piece opening May 9th for audiences to flock towards. For those on the fence, though, I whole-heartedly recommend giving its unique vision a chance and hope the following interview I had the pleasure of performing will help. Ayoade proves a soft-spoken, modest character with obvious intelligence and cinematic knowledge that’s quick to praise collaborators and poised to build a long and fruitful career in the director’s chair.

The Film Stage: Is it true that it was Alcove Entertainment who put you in touch with Avi Korine’s script? And if so, were you familiar with Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novella previously?

Richard Ayoade: It is true, yes. They had optioned Avi’s script because they had worked with his brother Harmony [on Trash Humpers]. I only had the book as a kind of trophy book on my shelf and I hadn’t read it. I only read it after I read Avi’s script.

Had making a dystopia such as this crossed your mind?

No, not at all. I liked the script and then read the novella afterwards and liked that as well. The book is quite hard to follow and it’s quite strange dialogue—it being in the third person makes it feel very subjective.

I just really liked the idea of a character who was so unremarkable that when his double appears in this way that it gets kind of crack up that no one notices. And when he points it out to other people they don’t care. That just seemed to me a very funny and unique way of taking that idea as opposed to the more gothic prospect of it causing a great scandal and an excavating or something like that you know? I guess Edgar Allen Poe‘s “William Wilson” story is much more gothic—he was more of a gothic writer.

But the Dostoyevsky one felt like it prefigured [Franz] Kafka and psychological concerns like the enemy—these ideas of the shadow. The idea of what you can’t accept about yourself. He took it into a much more personal space.

Now since Avi had done the original adapting, did you two go back to the novella for your collaboration or pick up from his script?

Well, the novella is always there and always providing clues as to how to take it, but, yeah, it was absolutely Avi’s idea. So for me … there are things in the finished film that are exactly the same as—not many, but a few key scenes—that are exactly as Avi first wrote them.

When you’re co-writing it becomes hard to say what you did or what the other person did because it becomes unimportant after a while. Because you’re both trying to work out what serves the story best and what would be right. For me it was a really enjoyable process whereby Avi did a couple of drafts and then I did a draft on my own and then I met him in Nashville a couple of times between his drafts. And then he came over to London and we wrote together for a while after I had done my draft and that was the time I felt we really kind of cracked it, when we worked in the same room together for a kind of prolonged period of time.

And then after that—when it got more into what I guess you would call a shooting script—I would work on it and then show Avi changes and things that came about either through various actors coming on or when the setting I guess changed and altered.

Talking about that setting—it’s claustrophobia, oppression, and anachronistic tech environment—it almost becomes a character itself. What influenced you to give time and place that imaginative ambiguity?

Well I think, with a lot of things, it often ends up being what you don’t want it to be. Initially it was going to be a sort of more modern, teeming metropolis. I just felt I had seen that a lot whether it’s from King Vidor‘s The Crowd or, gosh, I mean even City Girl the [F.W.] Murnau film—the start of that. Or The Apartment, Modern Times. You’ve seen that, you know, small man in the big city. I mean you’ve got Crocodile Dundee. [laughs] Just a million times.

Which is not to say it’s bad, it just felt like it’d be more interesting if the place he’s in felt more emblematic of how he felt. A lonelier place where there weren’t many people around. Where even though there’s all this space at work, for some reason it was still cramped and claustrophobic. One thing we liked which is not something anyone particularly would comment on, but there’s lots of space in this office and yet they decided to put them all in these tiny booths in the middle of it. For no good reason. Why don’t they let them spread out? I don’t know, to us we just found it funny—or I found it funny.

I just felt—again, with the idea of having a doppelganger come into this world—that it would be funnier and more absurd if there were very few people in the office. It somehow would make more sense in an office where there were a million people. But when there really are only a dozen people and they’re all really old and still no one notices that someone else looks exactly like Simon, that just felt even more absurd to me.

So it sort of came out of the reaction of not wanting to do, I guess, the most obvious thing. And then it started to become something that felt like it would be appropriate to have it all set at night. And we didn’t want it to feel like it was set in any particular time so that the audience wouldn’t be able to have the sense of, “Why doesn’t he leave this job? Why doesn’t he leave this town? Why doesn’t he go to Boston?” It wanted to be a world where there’s no escape and it’s completely hermetically sealed.

In that regard, a lot of talk after TIFF was comparing the bureaucratic dystopia to Terry Gilliam’s Brazil and you could almost say Submarine had a dry sort of Wes Anderson feel. Do you see those comparisons as flattery? Is it frustrating that the critical climate today is quick to categorize new directors?

It’s interesting because those are both two directors who have been accused of being derivative as well. In a way I think—just when anything comes out, often the job is to say, “What is it like?” Even if you just say dystopia, what directors are conjured up? It’s Gilliam and maybe [Jean-Pierre] Jeunet.

To me Terry Gilliam wasn’t an influence on this. Not that I don’t like him or—I love Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas. Brazil‘s not a film I’m particular familiar with except for I guess—what a lot of people have—a sense of it being very visually strong. But in a way I kind of feel he has a sort of particular satire or satirical approach to bureaucracy or corporate life that often have these sort of grotesques, these grotesque characters. Whereas I felt our world was more about loneliness and small characters. I guess it’s more—if you had to make a film comparison—like In the Mood for Love, the Wong Kar-Wai film. Or Aki Kaurismaki. But if you’re looking at an anachronistic bureaucracy, Gilliam is the poster boy for that I guess.

Yeah, I don’t mind. They’re both really good directors. I don’t know what—it’s a weird thing because you sound like you’re trying to defend yourself if you talk about it and if you don’t it sounds like you’re evading it. I don’t know what, in some ways, to say about it. Other than that every director who’s contemporary who I like now whether it’s Paul Thomas Anderson or [Quentin] Tarantino, most people about their films are always, “Wow, Paul Thomas Anderson just rips off [Martin] Scorsese and [Robert] Altman.” You know what I mean? I don’t know if this is like that. I don’t think people who said Magnolia was like Altman were kind of deranged, but it wasn’t really like any Altman film I had seen. [laughs]

You’ve quickly become one of the most innovative and stylistically assured directors today with your two films. So moving from—not that Submarine was “small”—but doing something here like the motion control and having to get two Jesse Eisenbergs on screen, what was it like to take that evolutionary step?

Well, our aim was to try and work out how we’d like to shoot it without bearing the motion control in mind at all. We didn’t want any shot to look like it existed in that way because that was how it made sense to shoot it. You know, these rigs are really big and unwieldy and there are certain ways to film that just make your life a whole lot easier. We tried to not have the motion control shots feel like motion control shots if that makes sense.

The main thing about it is that it’s incredibly time-consuming because you have to do it at least three times: one character and then the other character and then a plate shot. And you have to choose the first—the motion from the day. And that’s the most nerve-wracking bit. You have to commit without the luxury of distance and being in the edit and having an editor’s point of view as well. You stand and go, “It’s going to be take seven.”

So that aspect is strange, but Jesse is remarkable in his ability to be technically and incredibly precise without being I guess limited by the moves of that decision. He manages to still feel like he’s completely inhabiting it—and do these very technical things as well.

You used the same cinematographer, composer, and Submarine‘s five principal actors returned also. Did that help alleviate any anxiety to just jump in headfirst?

It’s certainly great to work with all of those people. Those five actors I really like a lot, so you have a shorthand that’s useful. And also because you spend a long time with them.

Sally [Hawkins], I’ve known—she was in this show I did in 2006, Man to Man [with Dean Learner]—I’ve known her a long time so you know what people are capable of. And so, often, because I’d seen Paddy [Considine], you know, on Submarine doing this thing, I knew he’d be able to do this kind of other role. And I knew that Noah [Taylor]—even though he plays a very kind of genial kind of person [in Submarine]—I knew he could play a real feckless, disinterested person because, you know, from just joking around with him.

I don’t know. You just have a sense of what people can do. Yeah, so it does help. It helped me.

And what is it about the eccentric, fringe character that attracts you? You have Oliver Tate’s misguided ego, Simon James’ introversion, and even Maurice Moss’ sort of nerd outcast. But there’s something endearing and relatable about them all.

I don’t know. In some ways I can take no credit for the creation of any of those characters because Joe [Dunthorne] wrote Oliver Tate and this character in The Double comes from the Dostoevsky via Avi’s first incarnation of it and Moss was written by Graham Linehan. And so, I like all of their writing and subsequently became involved—not in the writing capacity on The IT Crowd—but on the films.

Initially it feels interesting to see a character who is at odds with the world. I guess, you know, every superhero story is that as well. It’s a fundamental starting point for a narrative—someone who doesn’t quite fit in. And so that’s always attractive to see what their perspective is and to see how they are going to manage to connect. I guess that’s how I think everyone feels—maybe there are a few people who have always felt they fitted in—but I feel the vast majority of people don’t feel that.

The Double opens in select theaters and VOD on Friday, May 9th.