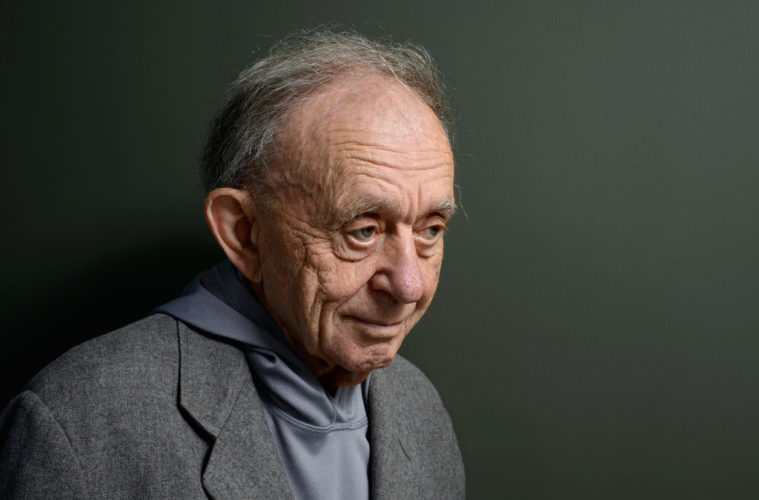

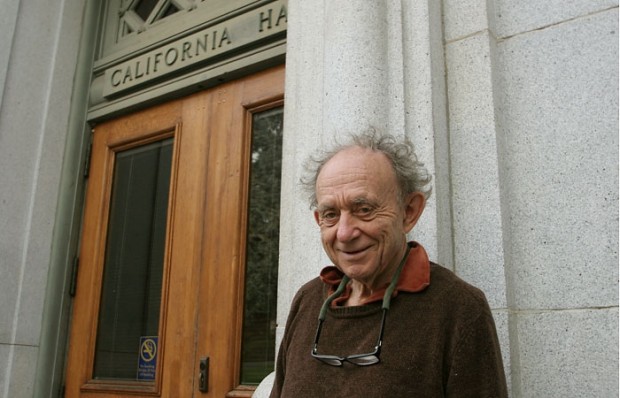

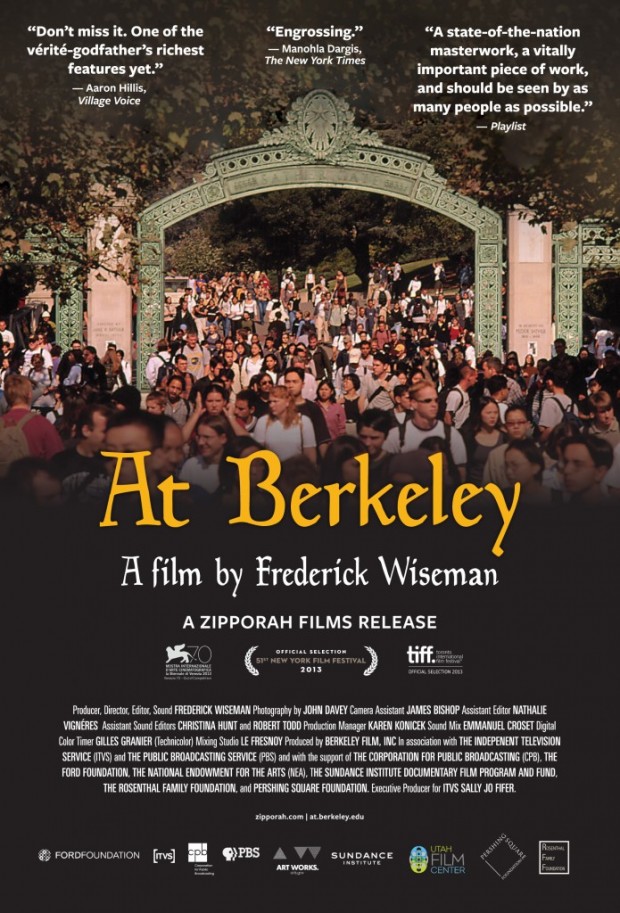

With his latest feature, prolific documentary legend Frederick Wiseman continues his cycle of examining institutions, beginning in a Massachusetts hospital for the criminally insane (his first feature, 1967’s Titicut Follies) to a cabaret in Paris (2011’s stunning Crazy Horse), and smaller spaces like 2010’s Boxing Gym, filmed in Austin, TX. Wiseman’s 41st feature film, At Berkeley, is of one of the year’s best, an intimate, sweeping portrait of campus life.

Wiseman is a fly on the wall in classes, during administrative meetings, and during the film’s final hour, on both sides of a student protest, jumping between the students and administration formulating both a security and PR response. A stunning portrait of a great university in a transformative time, the film is a study in transparent governance, even if it offers no easy resolutions. We spoke with Wiseman by phone from Paris, where he’s in post-production on his latest documentary, in which he focuses his lens on London’s National Gallery.

The Film Stage: It’s an honor, thank you for speaking with us.

Federick Wiseman: Thanks for wanting to chat me with me.

Can you talk about the cast and crew process and how you captured what might be the largest institution you’ve studied?

For a place as large Berkeley, or any place I’ve done this, there is no way you can be representative. You have to follow your instinct and judgment, and I knew I wanted to follow the way the administration was dealing with the economic crisis. I knew I wanted to go to classes and extracurricular activities, and get a sense of student life and all of that. I was set about doing that — one of the ways I did that was I had a consultant who was the retired Vice Chancellor whom I could talk things over and acted as my liaison with the faculty and, particularly, the administration. So when I wanted to find out what meetings were going on over the course of a couple of days or a week my liaison would call over to the chancellor’s office and get that information for me. And that way I could decide what I wanted to do. Once I decided that this week I wanted to go to a few English courses, my liaison to the campus would give me a list of which classes were on, and I would call the professor and make the arrangements to come into the class.

How much of the material ended up on the cutting room floor?

I started out with 250 hours of rushes and the film is mere four hours, which means I used 1/60th of the material.

I’m curious about the student groups, were they a self-selected bunch?

I selected them. I knew there were coral groups, signing groups, and I knew that would be interesting for the film. I got in contact with a bunch of them, and there was one evening where they had a tryout for the freshmen. So most of the major signing groups appeared that night, so it was easy for me to make contact with them that night if I wanted to find out what they were doing. A lot of it was luck, some of it was chance, and some of it is using judgment to where you want to be at a particular time.

There are some very interesting choices. I don’t recall any instance where you were following student-produced media around.

There’s one, an interview with an instructor about the financial crisis conducted by a someone from the student media. But that’s the only one.

Can you talk about the financial crisis and your interest on its impact on higher education? I should mention this is near and dear to my heart as I just finished an MFA at a public university within the SUNY system facing a lot of the same financial challenges Berkeley is. What was it specifically about this that got you interested in this story?

As you know, I’ve been doing a series on institutions and I wanted to do a university, but I didn’t want to do a private university, like an Ivy League school. I wanted to a do a project about a public university and Berkeley is the great public university in the world. So I wrote a letter to the chancellor and asked for permission. Then I went out to see him and was very grateful he granted permission. That’s how that developed, and when I met him, I told him I wanted to do a movie that would have a look at the way the university was administered. It seemed to me following the economic crisis; it would be interesting to see how the university dealt with a major issue.

Was there an awareness of your presence on campus as far as campus media?

Yeah, there was an article in the Berkeley newspaper. I like the idea that people know about the film because that means you have to explain less to people you meet. In fact, it opens doors for you, because someone will say, “I read the article in the student newspaper that you’re filming here,” and it’s a conversation gambit. You talk them for a few minutes and they say, “I have a really great English class. It’d be interesting if you could come to my class one day,” and there is kind of a daisy chain like that.

How long were you on the project, from writing the initial letter to deciding to stop filming?

I wrote the letter in the spring and started filming in mid-August — the shooting took 12 weeks.

I’m really impressed by the level of intimacy, that you’re able to be a fly on the wall at the faculty meetings and administrative retreat. Were there every any moments where they asked you to turn off the camera?

Yes, there was. For example, I couldn’t quite understandably go to any meetings where they were discussing tenure issues; that’s very private and the person up for tenure’s academic career was being discussed privately. I accepted that, of course. Generally speaking, anyone that doesn’t want to be photographed, they just have to say no and I stop – I won’t argue with them.

I was really struck by the conversation with the public safety administrators and discussing the tactical approach of managing protests, bringing in assistance external assistance and what was available from the county and so on. Was there ever any concern about making a lot of those procedures known?

No, they were quite open about that. It was interesting because the chancellor, Robert Birgenau, his point of view is that Berkeley is a public university and what goes on there should be transparent. Which is great; that’s the way democracy is supposed to function, not that they always do. That was his point of view and there was absolutely no hesitation from him to shoot this.

Often in the last hour you’re cutting back and forth between the officials formulating a response and the protests. Were you using two crews?

No – that’s an example of documentary filmmaking being a sport! You have to run between the buildings; fortunately the library where the protestors were and the administrative building weren’t very far away, but we had to make a judgment, when to be in the library and when to be with the administrators. I basically lucked out because I think I was in both places at the right times.

I agree with you on that one. Was there any concern with the level of transparency and how it would represent Berkeley?

They had no absolutely no editorial control, and the administration did not see it until it was completely finished, until it was mixed and timed. I sent them a DVD and they saw it, and I was pleased that they liked it. I never make a film where anyone else has any editorial control, either the place or even public television. I have complete editorial control over the film.

Has there been any dream intuitions you’ve wanted to go into that it hasn’t worked?

I had trouble in one instance, but 99% of the films I’ve had no trouble at all.

What is the pipeline for you next?

I’m working on a film about an art museum, the National Gallery in London.

The past few films you have made, specifically La danse and Crazy Horse, had a little wider distribution in terms of finding their ways into art house cinemas. Can you comment on the impact digital distribution has had on having those works reach a wider theatrical audience?

For years I couldn’t get my films into movie theaters, even now. La danse had quite a good distribution theatrically; it played quite broadly in America and 22 countries theatrically. Crazy Horse had some distribution, but there’s not a lot of talk these days about documentaries being big theatrical successes. In my experience I would categorize them as having modest distribution. It’s extremely hard to get them shown theatrically and I have someone who books them for me. I don’t have a distributor in the traditional sense, and if I did I would have to give them all the ancillary rights, TV, VOD, etc. I won’t want to do that because I’d never see a cent on the movie beyond the paltry advance I might get. Many years ago I set up my own theatrical distribution company [Zipporah Films] and when a film has a chance at theatrical distribution I hire someone who is never good at booking them.

I saw La danse and Crazy Horse both in commercial art houses – one in Montclair, NJ the other in Austin, TX – I imagine its it’s been easier now shipping a DCP now verses making a print?

Yes, it’s much easier shipping a DCP.

What are the distribution plans for At Berkeley?

It’ll be showing in two theaters in New York and it’s booked in either 20 or 30 theaters around the country. I’m hoping if it gets good reviews it’ll get booked more. But because of the length of the film it’s not easy to book this film, because you can only get two shows a day in. I think if the reviews are good we’ll have more. Once it’s had its theatrical run it’ll go out on DVD and VOD.

I look forward to it. I wish it were in wide release on 3,000 screens.

I think our booker is trying, but it is a matter of convincing 3,000 movie theater owners to have two shows a day instead of five!

We certainly need it in cities like Buffalo with large public universities. Thank you so much.

Thank you.

At Berkeley is now playing in New York and expand in the coming weeks.