Is it possible for images to swallow each other whole? Meaning a process in which each progressive striking composition not just tops the other, but rather summons a new tone and, in some cases, potential interpretation of the film’s overall meaning. While it would certainly be difficult for any film to maintain this continual shift of the ungraspable — i.e., when dealing with something so apparently amoral yet made with such dynamic conviction — questions of true intent become inevitable.

Sleek images are often used to sell evil, as evidenced by quick-cut television ads selling health-damaging products or two-faced politicians. In the extension of that visual language to popular cinema, though — an amoral sale taking place over two hours instead of thirty seconds — “evil” becomes serious business, for its point is far more belabored. But in that extra 119.5 minutes, the possibility for these images is to transcend from the didactic to the nihilistic; a piling-up of violence and vulgarity that makes us consider them in a different light. Though, for this to occur, you need not just an expert technician, but also an artist.

At this point in his career, Takashi Miike has reached a level of technical skill that he easily can rival any other studio craftsmen in producing these kinds of images, though he’s usually expected to make them “weirder” than that of the others. But this expectation can be unfair, as with his other film at Fantasia, the relatively restrained but expertly made Shield of Straw — a police action thriller which constantly has its characters navigating questions of morality, while Miike simply orchestrates their movements along that path — with his classicist touches (including many patient long takes) possibly distending it to a point, but still making them feel seriously considered. Its lack of bodily fluids — other than blood, of course — would possibly let down some of the genre-festival audience, however.

Thus Miike’s status as an auteur seems difficult to maintain; his acceptance of whatever action or horror script the Japanese studio system throws his way results in a muddled stylistic and thematic touch, as naturally anyone who makes three movies a year wouldn’t want to just do the same thing over and over again. This is not necessarily a negative quality, though, being that his formal ability can mutate to whatever he touches, and in the case of the pitch-black Lesson of the Evil, the subject matter constitutes him to go appropriately wild, to the degree that, as mentioned before, the images begin to “swallow each other.”

As for what, exactly, this subject matter is, it mines the Japanese school system, oft-satirized (especially in the almost-too-easily-comparable Battle Royale) for its pressure on grades, competitiveness of getting into university and overall hierarchy; the focus comes to a young high-school English teacher, Seiji (Hideaki Ito), well-liked by students, faculty and parents for his surprising joviality. But it doesn’t mean much in the face of inevitable problems: bullying, sexually abusive teachers, pressuring parents, and even the more classic, frequently texting (thus academically disinterested) students. So, obviously, as genre cinema would ask, the solution to all these problems turns not to a Dead Poets Society-esque inspirational method, but rather bloody murder.

Lesson of the Evil’s first two acts — before the third’s series of shotgun blasts and strikes against children — keep everything at a seeming arms’ length; the psychology of Seiji is difficult to parse, only because it takes awhile to realize the film itself is slowly descending from his social surroundings to the innards of his troubled mind.

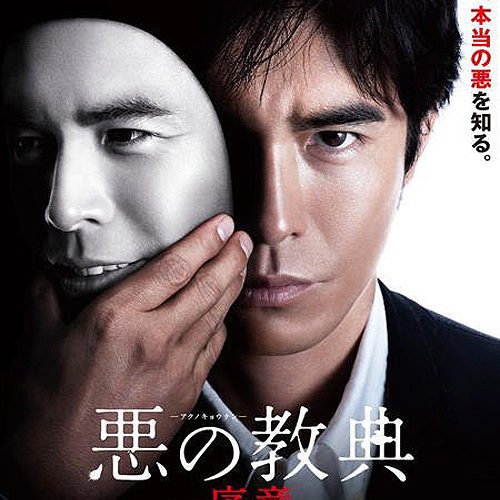

Though perhaps the easiest way of talking about Lesson of the Evil would just be to list every single one of its strange images and sounds — ranging from a flesh-adorned gun looking like something out of Videodrome, the musical motif of Bobby Darin’s “Mack the Knife,” the computer-generated-then-real ravens — that are all of a piece in a pure stream-of-consciousness. The progressive subjectivity of Seiji is always surprising and genuinely unnerving, thanks to Miike. Making some point about a handsome exterior hiding an evil interior is obviously tired at this point, but it’s still possible to be made fresh if a work genuinely dives into psychology or morality, which becomes unavoidable to contemplate when being bombarded with images of teenagers being gunned down — especially considering the stories of gun violence dominating the news as of late.

The amorality is overcome by the sheer force of the images, though, as if Miike isn’t interested in the justification of retribution, but rather the nihilistic freedom he’s allowed. It would appear that the seemingly blood-thirsty Fantasia audience that erupted in cheers upon every kill were in on his intent to some degree, removing themselves from any disgust by buying into the distance created through both its inherent ridiculousness and refusal of concrete moralizing.

Thus it can be concluded about Lesson of the Evil that, because of its ultimate removal of itself from social commentary and instead relishing of the film image, it at least operates under a guise of exploitation — all of which is welcomingly daft.