After teaming with Noah Baumbach to direct one of the best-ever documentaries about filmmaking, De Palma, Jake Paltrow is back with a new feature. June Zero is a vividly textured telling of the preparations for the 1962 execution of Adolf Eichmann through a triptych of perspectives––a Jewish Moroccan prison guard, an Israeli police investigator (and Holocaust survivor), and a clever and precocious 13-year-old Libyan immigrant. In advance of the June 28 release from Cohen Media Group, we’re pleased to exclusively reveal a series of influences the director has programmed for NYC’s Quad Cinema.

“Origin Stories: Jake Paltrow’s Notes on June Zero,” which runs June 21-27, features seven films that informed and influenced June Zero, with titles spanning humanist deep-cuts of world cinema from the likes of Miloš Forman and Abbas Kiarostami to underscreened classics of 1970s Israeli cinema. Watch the exclusive trailer for the series below, along with the full program lineup (including notes from Paltrow) and an exclusive clip from June Zero.

Le Trou (Jacques Becker, 1960)

This has long been a favorite movie and in our writing and casting processes the one my co-writer Tom Shoval and I talked about most in terms of building characters first on the page and then bringing them to life in casting for a magnetic group chemistry. A procedural masterpiece of camaraderie and betrayal that will break your heart.

Black Peter (Milos Forman, 1964)

We were working from such a low budget on a very short schedule that finding ways to simplify what we had planned became a daily ritual. Everything we had organized had to be slashed to half the shots in a third of the time. Milos Forman provided a master class in production economy with this movie. It is a treasure trove of great ideas and he developed a new dialect in cinema language to express them all with humor and soul.

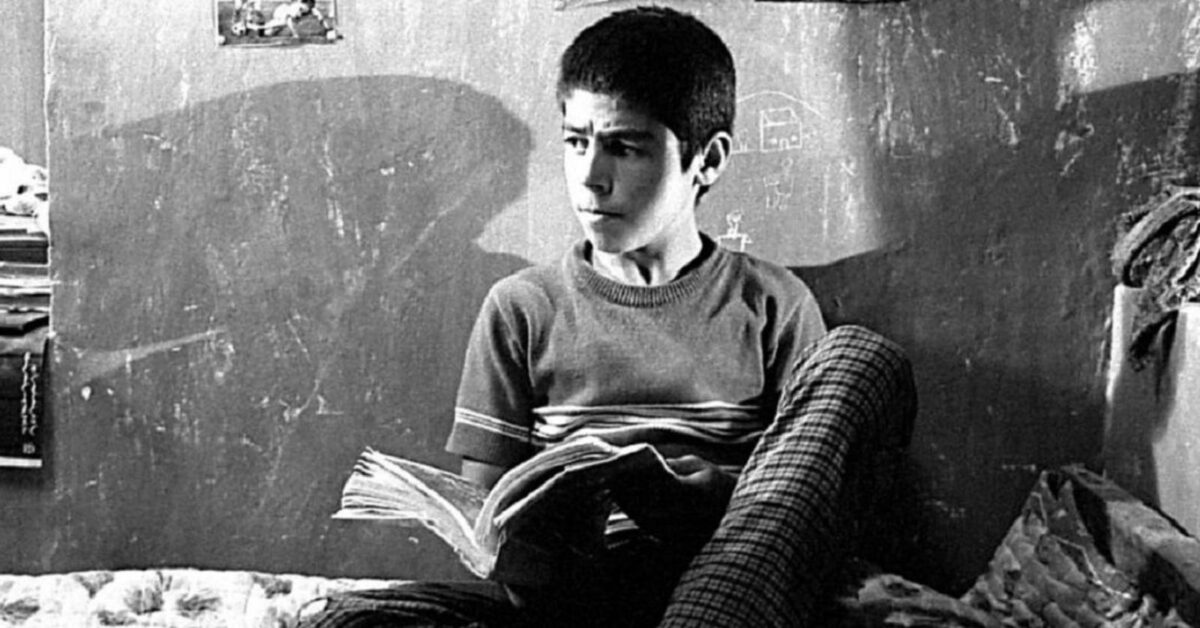

The Traveler (Abbas Kiarostami, 1974)

Jackies Coogan & Cooper, Jodie Foster, Jean-Pierre Leaud, Mickey Rooney, Quvenzhane Wallis, Freddie Bartholomew, and Tatum O’Neal are just a handful of names we associate with the greatest of child actors. The master Kiarostami brings us a young Hasan Darabi to add to the top of that list.

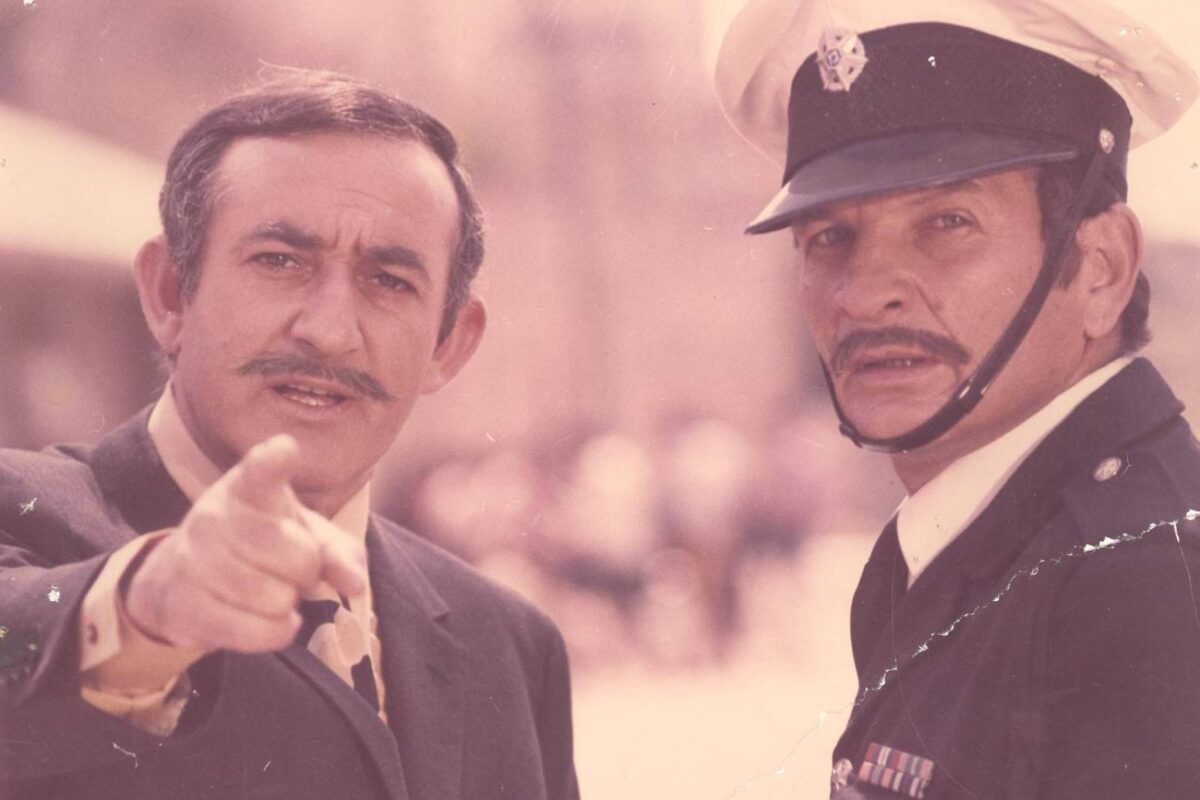

The Policeman (Ephraim Kishon, 1971)

This classic of Israeli cinema was nominated for best international film at the Oscars. Like Peter Sellers’s Chauncey Gardner and Inspector Clouseau, the policeman Azoulay (as played by Shaike Ophir) neutralizes the cynicisms of the classist paramilitary bureaucracy that controls his life and future through his bumbling guilelessness. Kishon stealthily skewers and celebrates the vast and chaotic diversity of this young country.

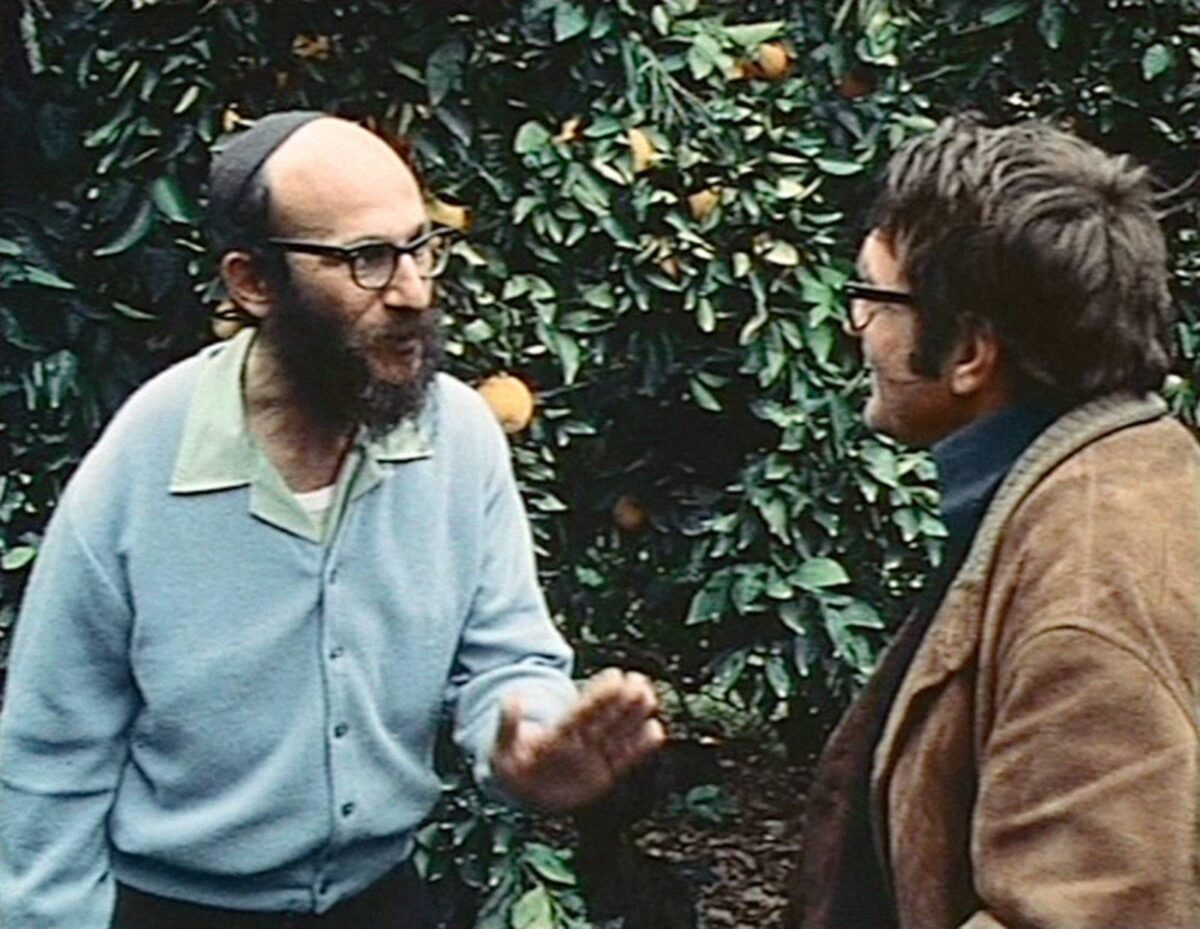

Pourquoi, Israel (Claude Lanzmann, 1973)

Lanzmann’s first film feels more courageous and urgent than ever. For a documentary that seems to boast in its very title that it will be about EVERYTHING he manages to generalize NOTHING. Like a magic trick it feels uniquely personal yet leaves not a trace of autobiography. Keep an ear out for the haunting Sarah Gorby lamentations.

Passenger (Andrzej Munk, 1963)

Like Fred Zinnemann’s The Search, this movie is as much a record of its location as it is a first of its kind of storytelling. Filmed in Auschwitz only 15 years after its liberation, this movie in many ways invents (and subverts) the very concept of what audiences would come to know as a Holocaust film.

Big Eyes (Uri Zohar, 1974)

Israel has one of the most under-viewed cinema histories and Uri Zohar is its Welles and its Rosebud. No one I know in the U.S. has seen Big Eyes. Zohar himself stars in this hectic tragedy and total self-immolation told against the backdrop of a Tel Aviv portrayed as chauvinist playground — a perception that Zohar’s previous movies helped create. The self-pitying machismo of his character Benny Furman is the heads to a coin that could be shared with Shampoo’s George Roundy on tails. Teaming once again on screen with best friend (and Israel’s answer to John Lennon) the rock legend Arik Einstein, they burn down the screen. It’s a confession and a resignation and after one more film Zohar would quit movies and became an ultra-Orthodox rabbi (a process he recounts in his autobiography WAKING UP JEWISH).