After earning an Oscar nomination for his incendiary 2008 documentary Food Inc., filmmaker Robert Kenner returns to issues about industry transparency with his latest film, Merchants of Doubt. Framed around the urgency of global warming as the new current issue, Kenner goes after the talking heads (Marc Morano, Steven Milloy, Peter Sparber, Willie Soon, etc.) who have been/are paid by companies to dispute scientific evidence with unchecked information or skepticism. Kenner’s film also unravels their playbook, exposing the tactics that create debates about non-debatable issues.

In an exclusive phone interview, The Film Stage talked to Kenner about his film, his vigor to question these so-called experts, the subjects who didn’t want to be on-camera, and more. Check out the full conversation below.

The Film Stage: What inspired you to make this film?

Robert Kenner: A few things. You bump into a few subjects, you follow a few threads, and then it leads you to wanting to make a movie. One of the first things that happened is that when I was doing Food Inc., I went into a hearing on whether to use clone meat, which is something I didn’t know that existed. I heard from someone say that it would be too burdensome to give them that kind of information, and suddenly I was in this Orwellian world.

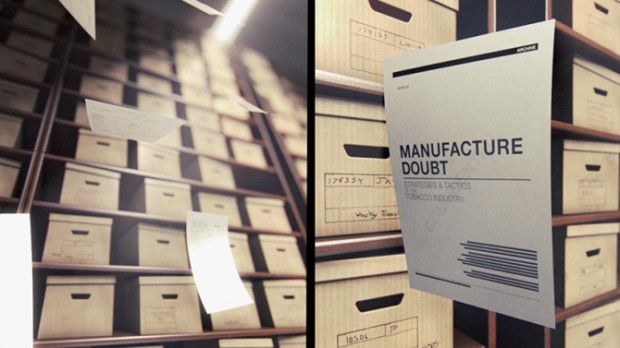

And I read [Naomi Oreskes’and Erik M. Conway’s] book of the same title, which is in a way part of the inspiration but not what the movie is. And ultimately, I thought that this was a continuation of Food Inc., that this is a film about transparency. You become interested in the guys who were able to say there was a debate about tobacco, when they knew for 50 years that it caused cancer. And all about their techniques on delaying regulations with tobacco, and how successful they were with them. Anything that was killing you, they would go work for them. They were really successful, and knew to doubt, delay, or attack the message.

And the playbook, when you have these guys that can play into that and create doubt and to have a media that’s not following up, and asking the right questions. And I’m not just talking about Fox News. It’s to see people Stephen Milloy who really is being paid, or Willie Soon, one of the most prestigious climate deniers, who is getting $1.2 million from coal companies and he’s not just getting the money, he’s writing science reports for coal companies, and people were not investigating that. And he was just referring to himself as a Harvard scholar, and he’s not. That’s the problem. How does this go unchecked? You find people who are misleading about other issues like tobacco or the climate, and then you have a media that is not digging through and finding the answers.

What advantages do you think the documentary has in presenting these issues over how newspapers do it?

As investigate news stories are sort of diminishing because of newspapers, and the decline of newspapers, and there’s a power that documentaries have, that film has. The power to be emotionally moved by things, I think is greater on film than in print. And i think documentaries are affecting people in a very strong way. I certainly saw that with Food Inc., and hope to see it with this one.

People knew that Food Inc. had an impact, aside from being one of the top grossing documentaries we were one of the most successful docs in the DVD and on demand realm. I think people were curious because of that and interested, and on some levels the film was not an anti-corporate film, but it crossed ideological boundaries, Republicans, Libertarians, Democrats, they like the film because people care about what they eat. I think people will also care [with Merchants of Doubt] that they’re being lied to looking at the tobacco playbook that was so successful. It’s a clever form of misleading. They didn’t say cigarettes don’t cause cancer, because they can’t say that, they had all these other excuses, which is anything to delay. By being able to show those patterns of misleading people, and to hear those exact same words and repeat them, that might be stronger in film than in print.

Do you see yourself as a filmmaker, or a journalist?

I think of myself as a filmmaker and not an investigative journalist. I like to have a social or moral undertone when I do films. I love meeting people, and I love working with new people and getting to understand them even if they think of the world differently than me. This [film] is going to be a little more strained, but I look forward to getting to a more less-strained process.

What was the editing process like for this film? How long was the first rough cut?

It was a really hard editing process. I have no clue what the original length was, I’ve blocked it out of my mind [laughs]. We had so many different sections that would go in and not go in, and there were a bunch of great scenes that got lost. We called it “drowning your puppies”in the editing room. Like there was a Tea Party lady, Debbie Dooley, whose outrage was that it’s against the law to rent solar panels, that you can only rent the panels from the electric company, and you return the energy to them. And places where they’re making it really hard to rent electric panels, ands they’re starting the Electricity Freedom Act. Debbie’s a Tea Party member who said, “Wait a second, it’s hypocrisy, these guys want to continue business as long as it’s their business, but they want regulations if it helps them.”It just points out the hypocrisy of these guys. But it’s interesting to meet someone who started the Tea Party, and then [you] find out you have this relationship.

Did you have a different audience in mind, or the same audience, when making this film, as compared to Food Inc., or even When Strangers Click?

Certainly different than strangers. But it is pretty similar to Food Inc., I hope. I hope we reach across the ideological boundaries, I’m sure we aren’t going to reach some people. and the fans who like Food Inc., I hope they believe what we’re saying. and perhaps like Food Inc., I’m hoping Merchants of Doubt causes the media to look at the issues.

Have you heard any responses from the people you’ve mentioned in the film?

We’re starting to get attacked with lawsuits [for Merchants of Doubt], but that’s what the playbook is. We’re getting friendly letters from Dr. Singer saying, “We’re thinking of suing you.”He has not seen the film, which I thought was really quite interesting, and he’s disclaiming that we say things he doesn’t say. He’s framing it to say that if he thinks something is true, even if it isn’t that he’s not a liar [laughs].

How did you position yourself concerning what this project was about when talking to your subjects?

Well, people had seen Food Inc., and I said I am trying to figure out how you do what you do. Marc Morano was an absolutely personable fellow, quite charming and quite funny, and in some ways very honest. I’m grateful for the opportunity to have been doing a peek behind the curtain to how things work, and I was flabbergasted at Marc’s honesty. In a way, the most interesting thing is to understanding it through the eyes of the deniers themselves. I would have liked to have had that more than I did. Peter Sparber actually returned my calls, he never returned a reporter’s call for years, and I told him that he’s so good at what he does —he was able to convince people that cigarettes didn’t cause fires, and I thought that was a pretty miraculous thing. And I said we’re not just doing cigarettes and we’re doing a film on the playbook and we’re going after climate, that’s where the money is today, that is where the action is. To which he said, “You could take James Hansen and I could take a garbage bin and I could say that the garbage bin knows more than he does.”But in the end he didn’t do [the film]. He said, “You could make a great movie without me, and I could live a better life without you.”

Who else did you interact with when trying to make the movie, that didn’t appear?

Well, with Steve Milloy, we spoke for months. He just said, “I am trying to do the right thing.”And that’s not true. He was hiding, to appear as an independent person giving his own personal beliefs. He’s a hired gun for cigarettes, asbestos, and whatever’s basically killing you, he gets paid a fortune. We were talking, and I flew with my crew to Washington, and after we arrived, he canceled. I know he had just signed a major deal with a coal company, and as I say, “If it kills you, Steve’s there.”

Lastly, with Food Inc.’s impact on the fast food industry, what are your thoughts about the recent change of leadership at McDonald’s, which is going to push the company in a more transparent direction?

It’s an example of how business can lead change. I don’t think there is a debate on whether CO2 forms the atmosphere, but there is absolutely a debate on how you can solve the problem. You can have business like McDonald’s that lead the charge, but that’s a real debate. The solutions are real to talk about, the problem is not real in this particular case, or in tobacco or asbestos. I think business could be the solution, but for capitalism to work, you have to see charge for the damage you’re doing. If you’re polluting air, what are the health effects? Like with tobacco, what are the health effects? You’ve got to see what the cost is.

Merchants of Doubt is now playing in select theaters, and expands to additional markets, including Chicago, on March 13th.