It wouldn’t have been Sundance without at least a handful of coming-of-age stories. Sean Wang’s audience award winner Dìdi (弟弟) proves that, with a new perspective, there are still emotions to be mined from a tried-and-true formula. Exploring the everyday life of a Taiwanese-American boy growing up in Fremont, California, wherein issues of friendship and potential crushes can seem to consume every waking moment, the film is most impressive in how it completely nails its 2008 milieu. From trading AIM messages to being obsessed with MySpace Top 8s to looking up how to kiss through YouTube tutorials, it’s remarkable how these nostalgic touches are conveyed with more fondness than cringe.

As the film rolls out in theaters, including a wide expansion on August 16, I spoke to Wang about crafting his feature debut, not dipping too heavily into nostalgia, working with modern-day teenagers, coming-of-age influences, the battle to choose the film’s first still, advice for first-time directors, and the meaningful experience of having a substantial theatrical release.

The Film Stage: I grew up in the same era, learning the internet in the same way with MySpace and AIM and all that. How did you choose what to show and what not to show, to not tap too heavily into nostalgia? I’m also curious about that aspect of the technology and how you actually recorded it. Did you have to have graphic design done, or did you find the past programs and actually use them?

Sean Wang: No, I wish we had the past programs. That would have been a freaking godsend. We really, painstakingly recreated every asset you see in the movie. There is a website called Space Hay that actually we used a lot as research. With what we included, obviously, it was going to be nostalgic in nature just because of the essence of what it is. And so there were certain things that I knew would be, like, little dopamine hits that I was like, “Oh, we got that buddy icon in there. I think people will know that.”

But I think there’s just something inherently nostalgic about seeing old internet UI, like these user interfaces, have meaning in our lives. They mark different chapters of our collective existence and so I knew going in that first time we cut to a wide of the computer screen, I know people are gonna be like, “Whoa!” But the hope is that once you get over the first rush of the AIM sound, the old YouTube, and the Mozilla Firefox, then it just becomes part of the world. It doesn’t become nostalgic after the first time you see it, and it becomes story-driven and it becomes just part of this character’s life. You know, we were living our lives half-online at that time.

I also love the authenticity of the dialogue, particularly the dinner-table conversations, how people are yelling over each other. What was your approach in scripting that and talking with the actors about how to perform? I imagine it’s more complicated than we might think.

Yeah. I mean, that one was tricky just because family dinner scenes are really tricky to shoot because there’s so many eyelines and there’s so many angles you need to cover. It’s just deceptively complicated. The hope is that you’re always kind of rooted in his perspective on that scene and you’re taking things in from his point of view. I knew I wanted that scene to start at this very quiet, domestic, quotidian snapshot of a family that then escalates into everyone talking over one another and it’s like a cacophony of noise and no one understands anything. That’s almost like the arc of the film, right? It’s the most quiet and the most chaotic. And I was thinking, “Can we have that in one scene that also establishes every family dynamic that you see for the rest of the movie?” It was really fun to shoot that and bring it to life.

Since you worked with modern-day teenagers, did they think anything was wildly different 16 years ago compared to their experience now?

Izaac [Wang] says the slang now is much better. He was like, “What the heck were you guys saying back then?” And that was a lot of the direction with these kids. It was like, “That take was great, just don’t say ‘deadass.'” And they’d be like, “All right, bet.” And I’d be like, “Yeah, don’t say that either.”

But, you know––the obvious things, right? Like flip phones and T9 texting, but otherwise there wasn’t a ton of stuff I had to teach them. It was really empowering them to be a teenager today, as opposed to try and put yourself in the headspace of being a teenager in 2008. I think the bet I took was: it’s not that different. The way we dressed is; the emotions, I think, are the same. The way they talk, the energy, the stupidity, the irreverence––it’s all the same. Everything around it is different, but that’s our job; they didn’t have to worry about that. We’ll find the clothes and we’ll do all that stuff.

I enjoyed the heightened emotion you bring to something that, from an adult’s point of view, might be a very small thing, but from a teenager’s perspective it’s their entire world. I’m thinking of when he runs home to delete the YouTube videos, which is kind of like his whole personality up to that moment. How much did you want to convey that overwhelming anxiety?

I mean, yeah––that was the hope, right? You’re putting the skeletons in the closet, and it was just like, “I need them to not see the videos of me kicking my friends in the balls.” Like, what are the things in my current life that I need to hide? What are the parts of me that I need to hide to be accepted by this different group of friends? And that’s so much of what the movie is. What parts of myself do I hide to be accepted with this group of people that I want to be a part of? And so that’s just like a microcosm of a theme that’s kind of repeated throughout the whole movie.

I was watching your New York Asian Film Festival Q&A, and you mentioned some touchstones like The 400 Blows, Yi Yi, and even Lady Bird. What do you think works so well in those coming-of-age movies that you wanted to carry through in your own way?

I think just how emotional and honest the relationships were between the boys [in Dìdi (弟弟)]. They felt like real boys and their emotions felt true to boyhood. And they were irreverent and immature, but also emotional and sad and lonely and confusing, and I think that’s what adolescence is. And so I think I wanted to try to make a movie that was about kids, not necessarily for kids, because I think a movie for kids is impossible to kind of depict it accurately because their emotions are scary.

I like how you don’t end on a clean note. How important was it to leave things hanging and how this is just one step in this character’s life?

Yeah, I didn’t want any of that ending that just felt, like, clean. I do think our ending is hopeful, but I didn’t want it to be that type of coming-of-age movie where it’s like the protagonist all of a sudden has this big realization. He’s like, “Wow, now I’ve learned a lot, and I’m going to high school.” It’s just… that’s not how life feels. And so I wanted it to feel hopeful but still hopefully real and grounded and true to life, in a way.

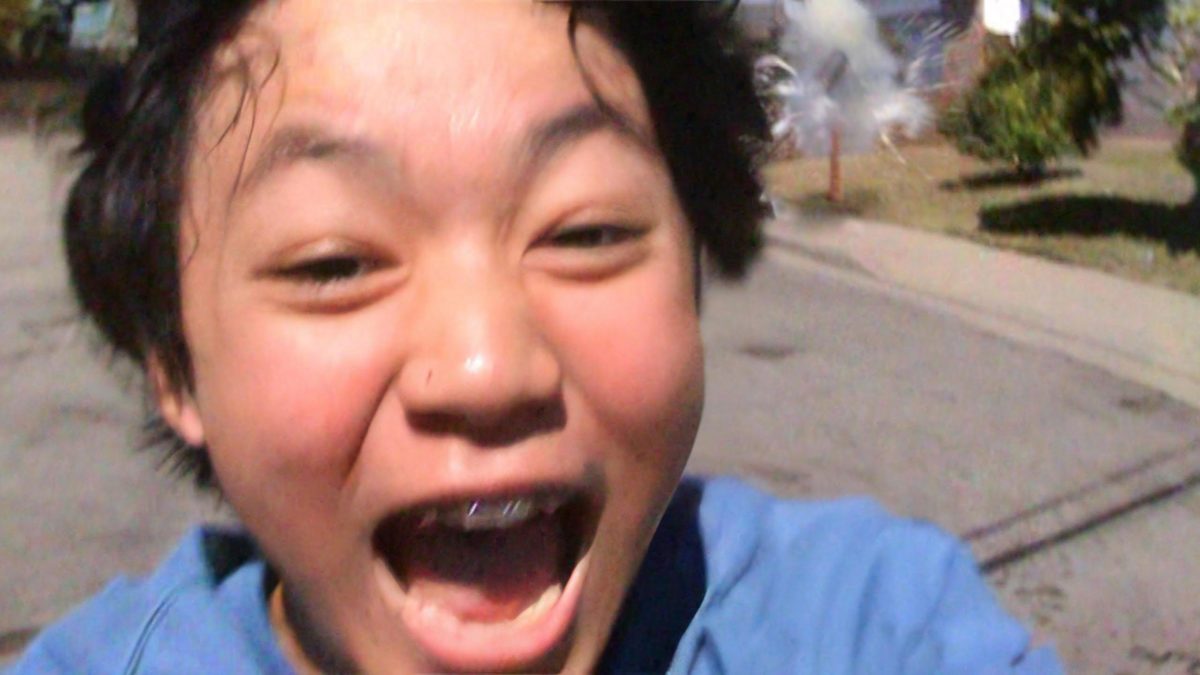

This is more of a marketing question, but I’m always fascinated when the Sundance lineup comes up and see the first still from every film, your first glimpse at the next year in cinema. And I really love the one you chose here because it’s not so reflective of the cinematography of the film. It has a very different energy to it. Was that your choice from the start?

Oh, my gosh. It’s very interesting that you bring that up. It’s a long story, but it was my first choice as a still. And then it went through many, many, many, many, many emails and conversations and roadblocks about, “Are we sure that’s the still?” I remember when I was like, “Yeah, this is our hero still for the Sundance lineup.” And they were like, “It’s a little blurry. Can you pick a different one?” And we’re like, “It’s what? It’s supposed to be blurry, you know?” And it really became, like, a big sticking point. But ultimately I think it went back to just, I don’t know, “It feels right. It captures the energy and irreverence of the movie. I can’t find another still in the movie that excites me as much as this one.” So much of this movie was just following your intuition and kind of being like, it might not be the “correct” still and it might not be the still that’s traditionally safe for a movie. But none of the choices we made on this movie were, I think, traditional in any sense. So it kind of just continues in the ethos of surrounding myself with people who encouraged me to trust my intuition, to make this movie as specific and unique to me as possible, and hopefully other people would resonate with it.

That’s great. It definitely stood out. With this being your feature debut, I’m just curious what you learned most from this experience––both positive and negative––that you would take on and either do differently or make sure stays the same for your next feature.

I want to continue making things I feel really strongly about that come from within. I don’t see myself as a director who just makes their first movie and all of a sudden I’m just, like, a Hollywood director for hire. I’m okay with taking my time. Especially because I’m 29 and I don’t have a family, and I don’t really have to make big, life-altering decisions. I want to make sure I can take my time with the films I want to make, because they do take years. I think about that a lot. The next movie I make, whatever it is, I’ll be in my mid-30s, you know? And then I’ll probably start thinking a lot more if I do want a family. But right at this very moment, I get to be a little bit selfish with what I want to pick and choose. So I’m okay with taking time next.

What would be your advice to directors who are attempting to make their debut?

I would say be patient. Take your time. I think there’s some weird [perception] that you have to rush your first feature. You’re not a legitimate filmmaker until you make a feature. I don’t know––it’s, like, industry B.S.––but I think take your time because they call it a debut for a reason. You’re really putting something out there that is hopefully indicative of the stories you want to tell and who you are as a filmmaker. You only get to debut as a filmmaker once.

Focus Features is giving Dìdi (弟弟) quite a substantial theatrical rollout. How important is it for you as a filmmaker to get an audience to see this in theaters first and have that kind of communal experience?

It’s everything. I really wanted to see a 13-year-old Asian boy giant on a screen and to be like, “This kid’s story matters.” Like, this is a big-screen story. I think that was always the bet. And that if we could really root yourself in his perspective it would feel like a big movie. It would take you on a journey. And so, yeah: the fact that we get to have a big theatrical rollout is very cool.

Dìdi (弟弟) is now in limited theaters and expands on August 16.