Dailies is a round-up of essential film writing, news bits, and other highlights from across the Internet. If you’d like to submit a piece for consideration, get in touch with us in the comments below or on Twitter at @TheFilmStage.

After two years, Charlie Kaufman‘s Anomalisa has wrapped principal photography.

Ida dominates this year’s European Film Awards winners.

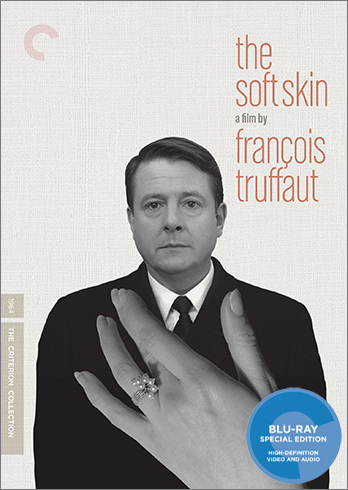

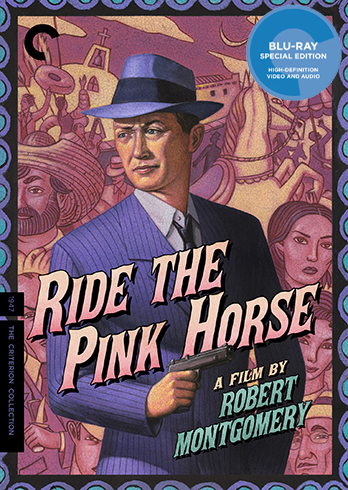

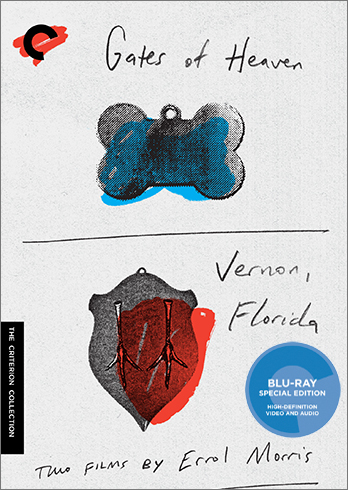

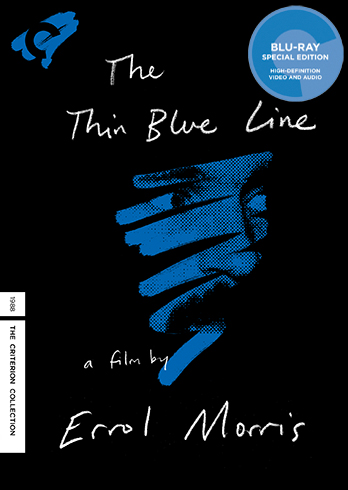

Criterion has announced its March 2015 line-up (click titles for details):

At The Talkhouse, Bret Easton Ellis discusses Paul Thomas Anderson’s Inherent Vice:

It’s hard to believe that the new P.T. Anderson movie is the first of Thomas Pynchon’s books to be finally visualized — Pynchon has published eight novels over 55 years and is among the most revered and legendary of American novelists, and though Pynchon does write cinematically, the convoluted and rangy narrative structures and the jazzy, coolly hyperbolic prose and the surreally over-scaled and outrageous situations he puts his characters in aren’t really suited to conventional large-scale mainstream moviemaking. Like with most great prose stylists, you read Pynchon because of the poetry and getting lost within enigmatic labyrinths rather than enjoying the pleasures of a straightforward plot revealing itself. And the books are usually epic: How can we “see” a full-scale realization of Gravity’s Rainbow or Mason & Dixon without spending hundreds of millions of dollars on their cinematic adaptations? If you’re alienated or intimidated by Pynchon’s elaborate playfulness then Inherent Vice might be the one novel of his that offers a way in — a plotty and free-wheeling psychedelic take on detective novels, set in 1970 LA. It’s probably (except for Vineland) his least major work but it’s the tightest of Pynchon’s novels (though one might argue The Crying of Lot 49 is) and it has a mystery that culminates into an identifiable conspiracy with conventional closure — and there are loose takes on recognizable archetypes: the patsy, the femme fatale, the crooked cop, the tycoon.

At Wondering Sound, Glenn Kenny interviews Paul Thomas Anderson about the music of Inherent Vice (which can be listened to here):

Early in Inherent Vice, the latest film written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson — and the first authorized film adaptation of a novel by American literary giant Thomas Pynchon — the lead character Larry “Doc” Sportello stands out in the street in his small beach town, befuddled as he looks for someone who’s receding into the distance. As the shot holds him in a medium close-up, the song “Vitamin C” by the venerated German psychedelic combo Can comes on the soundtrack. An insistent stumbling drum beat and a bass line that zig-zags, it’s a nervous song, and the vocals by the group’s then lead singer, Japanese-born Damo Suzuki, carry appropriate anguish. I’ve always considered Suzuki’s lyrics on Can songs as little more than ESL-free associations, but in the context of Doc’s interactions with his now semi-kept-woman ex-lover Shasta, the line “she is living in and out of tune” has a very specific ring in the shot, as does Damo’s repeated cry “Hey you! You’re losing, you’re losing, you’re losing, you’re losing your vitamin C!”

…and Kenny also writes about man and beast in Inherent Vice:

“He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man.” Hunter S. Thompson used that Samuel Johnson observation as the epigraph for his 1971 Fear And Loathing In Las Vegas, and one of the many things Thompson achieved in that ruthless work was in revealing the pain that even good men are capable of inflicting once they’ve made beasts of themselves. It’s not for nothing that Terry Gilliam, adapting that book into a film in 1998, made Chapter Eight of Part Two of that book, in which Thompson and his “attorney” terrorize a diner waitress, into the most nakedly exposed raw nerve of the story (Ellen Barkin is exceptionally jarring in the waitress role). In his extremely appropriate adaptation of Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice, writer/director Paul Thomas Anderson makes some very distinct shifts of stress to, among other things, bring an almost Gravity’s Rainbow level of despair and pessimism to bear on what is, I reckon, the coziest finale of a Pynchon book to date. And, as in Gilliam’s adaptation of Thompson, the shift into a darker tone finds its footing in a scene of unpleasant interaction between man and woman.

At Vulture, Bilge Ebiri on the Sensory Ethnography Lab:

The most exciting documentary films being made today come not from a brand-name auteur or even some up-and-coming, Sundance-anointed visionary. Rather, they come from a place called the Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab, which sounds more like somewhere an ophthalmologist might send you than a source of great filmmaking.